Rüya Irmak Öney

Traineeship Program Participant

1. INTRODUCTION

The issue of the far-right is getting more and more attention in world politics. This is also valid for the context of Europe. It is possible to see the increasing effects of far-right parties and their leaders in European political life. Also, within the last years, there has been a significant increase in the vote share of Eurosceptic parties. This situation can be seen in the European Parliament results, especially in the years 2014 and 2019. When the attitude of far-right parties towards the European Union is examined, it can be said that the majority of them tend to be Eurosceptic. Thus, to some extent, the rise of far-right parties also contributes to the rise of Euroscepticism. Based on that, the rise of far-right parties who adopt a Eurosceptic attitude can create big problems for the future of the EU. Considering the current political problems of the EU, this issue creates another challenge for European integration. The United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) can be cited as an example of this situation. UKIP is a far-right Eurosceptic party in the UK. If the results of general elections are examined, it can be said that UKIP is not able to gain any important electoral success. However, in the 2014 European Parliament elections, with gaining 27.49% of the votes, UKIP became first-party [1]. In addition to that, the party's impact continued in the Brexit referendum with the effective electoral campaign of their party leader Nigel Farage. Considering these, it can be concluded that this far-right party had an important impact on the rise of Euroscepticism in the UK and even the exit of the UK from the EU. It is possible to see similar significant effects of the far-right parties of EU countries by other far-right parties. Therefore, it is an important issue for the EU. So, the main question that will try to be elaborated in this paper is “How the European far-right parties and Euroscepticism are related?”. In order to answer this question, first, of all the far-right parties and Euroscepticism will be analyzed with a general view. Then, the cleavage theory that will be used to examine the question will be explained. After that, a general overview of the current situation of far-right Euroscepticism will be provided. Moreover, the cases of France and Italy will be examined. Front National from France and Lega Nord from Italy were chosen. The reason for choosing these parties is that both of them are important far-right parties who have a huge impact on their country. For the time period, the current situation will be examined by considering the last two European Parliament elections in 2014 and 2019. In this last section of the paper, a general conclusion based on far-right Euroscepticism will be made.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

In this part, the main concepts of the paper, far-right and Euroscepticism, will be defined. Then, the literature with respect to the relationship between far-right and Euroscepticism will be provided.

To begin with the far-right, it can be said that defining the far-right is not easy. Even the scholars are not able to come up with one precise definition of the far-right. In this paper, the definition provided by Cas Mudde will be used. He defines far-right as an umbrella term that includes both the extreme right and the radical right. The main difference between them must be highlighted. Mudde argues that the viewpoint of the extreme right and the radical right on their perception of democracy creates the main difference [2]. In this respect, while the extreme right is antidemocratic, the radical right is anti-liberal democratic. This means that extreme rights oppose democracy as a whole. On the other hand, the radical right does not completely deny the notion of democracy. It only opposes the values of liberal democracy. Mudde also states that “The most relevant subgroup within the radical right is the populist radical right, which includes almost all relevant far-right parties in contemporary Europe.”[3] Therefore, in this paper, the main emphasis point will be on populist radical right parties (PRRPs). This categorization is also very useful for analyzing our cases because both Front National and Lega Nord are classified as populist radical right parties. Mudde explains three core ideologies of the far-right nativism, authoritarianism, and populism[4].

Firstly, with respect to nativism, the far-right wants to preserve the nation-state. At that point, the far-right is against any kind of action that can damage the homogeneity of the nation-state, i.e., non-native groups. Secondly, authoritarianism is strongly related to the consolidation of an ordered society. Lastly, Mudde and Kaltwasser define populism as “a thin-centered ideology that considers society to be ultimately separated into two homogeneous and antagonistic camps, “the pure people” versus “the corrupt elite,” and which argues that politics should be an expression of the volonté générale (general will) of the people.” [5] In addition to these three core features, Vasilopoulou argues that there is a tendency among far-right parties to be ruled by strong and influential leaders[6].

The second key term is Euroscepticism. The emergence of the term Euroscepticism can be traced back to the 1960s. Hooghe et al. argue that the term was first used by The Times on 30 June 1986 for defining the position of Margaret Thatcher with respect to the EU[7]. Vasilopoulou basically defines Euroscepticism as a “term that describes negative attitudes towards European integration.”[8] Taggart and Szczerbiak differentiate two types of Euroscepticism as hard Euroscepticism and soft Euroscepticism. According to them, hard Euroscepticism provides principled opposition to the EU and European integration. This even includes a desire for their countries to withdraw from the EU. On the other hand, soft Euroscepticism generally focused on concerns with respect to a few specific policy areas. Soft Eurosceptics highlight the importance of national interest against the decisions of the EU.[9]

With respect to the relationship between the far-right and European Union or European integration, it can be said that far-right parties generally adopt a Eurosceptic attitude. Werts et al. argue that “Political and cultural European integration goes against the core ideology of the radical right-wing party family that Europe exists of unique nations with differences that have to be preserved.”[10] As noted above, nationalism is one of the core ideological features of the far right. The EU leads to the opening of borders and increases cultural homogeneity. At that point, Pirro and Kessel argue that because of these features of the EU, it is perceived as a threat to national sovereignty by PRRPs[11].

However, it is needed to highlight that Euroscepticism does not mean totally rejecting the EU. There is a distinction between Eurosceptics and Euro-rejects. Former one finds the practice of European integration problematic, but they are not against the idea of European integration. However, Euro-rejects completely reject the idea of European integration. [12]. In this context, Mudde categorizes PRRPs as Eurosceptic by suggesting, “The majority of populist radical right parties believe in the basic tenets of European integration but are skeptical about the current direction of the EU”. [13]

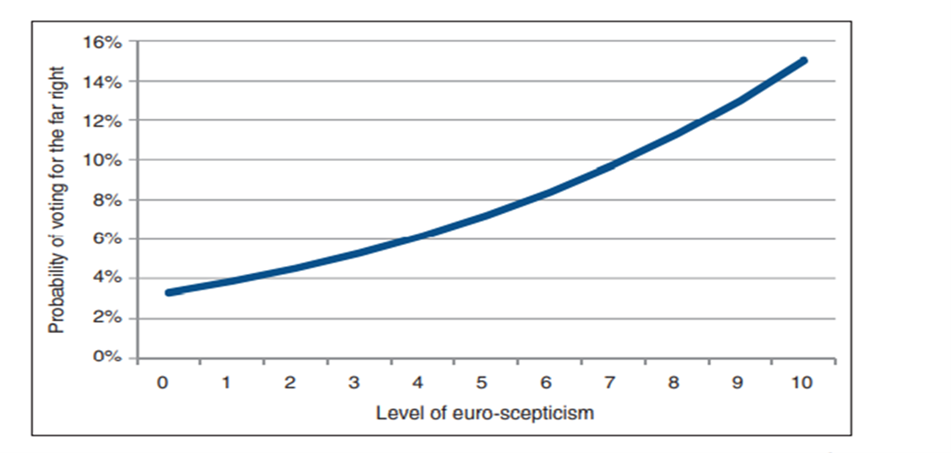

Werts et al. also suggest that there is a positive relationship between the level of Euroscepticism and voting for the far right[14]. As it can be seen from the figure below, while the level of Euroscepticism rises, the probability of voting for a radical right-wing party also rises. Here it can be concluded that Euroscepticism is a factor that is used for explaining the vote for the radical right.

Figure 1: Probability of Voting for the Far-right and Level of Euroscepticism[15]

Moreover, the relationship between far-right parties and Euroscepticism can vary with respect to changing conditions. Pirro and Kessel claim that “financial and economic crises offered scope for PRR parties to increase their opposition against Europe.”[16] This means that PRRPs basically blame the EU and its governing elite for the bad situation. So, the degree of Euroscepticism of far-right parties can vary at different times. This point is important because it is always possible to be emerged new conflicts or crisis in the areas such as immigration and the economy. Considering this, if the reaction from far-right parties becomes too sharp, it can lead to further problems for the process of European integration.

3. THEORY

In order to understand why the vote share of far-right Eurosceptic parties increased, I will use Cleavage Theory. Cleavage Theory is used to understand the main political dynamics of Europe. It was originally developed by Lipset and Rokkan in their foundational work Party Systems and Voters Alignments. With respect to the classic cleavage model, Lipset and Rokkan argue that there are four main cleavages that structured the European party system, which is center-periphery, land-owning- industry, state-church, and property-work. [17]While formulating their ideas, Lipset and Rokkan focus on two main revolutions, National Revolution and Industrial Revolution. It was argued that the European Party Systems are frozen since there is no new revolution.

The Rokkanean model is still very important for the study of European Party systems. However, since the development of the model dates back to the 1960s, there are some new conceptualizations with respect to cleavage structure. In addition to these cleavages, some scholars, such as Kriesi et al., conceptualize a new type of cleavage, Globalization Cleavage[18]. This conceptualization is mainly based on the distinction between winners and losers of globalization. Losers of globalization are basically defined as a group of people who think that their comparative advantage status in society is gone because of the new circumstances. Here it can be seen that globalization does not affect everyone in the society in the same way. Globalization negatively changed the relative position of some people in society. This viewpoint can be considered in line with Rokkanean conceptualization because they reflect globalization as a revolution. Martin also uses the term Global Revolution. In this respect, Martin mentions the emergence of new cleavage between identity and cosmopolitanism[19]. The emergence of the global revolution can be traced back to the period after 1945 when international organizations such as NATO, UN, and EU were created. Undoubtedly, globalization has enormous effects on national borders. It can be seen that with globalization, the importance of national borders decreased. Globalization fosters mobilization in transnational, international, and supranational ways.[20] In this way, it also increases cultural diversity and makes the society more heterogeneous.

The multiculturalism that globalization brings is seen as a threat to national identity and national sovereignty by the losers of globalization. Therefore, it leads to the emergence of a group of people who feels like their identity is under threat.

This globalization cleavage is very useful to explain the rise of far-right parties because the voter base of far-right parties consists of the people who think that their current status is under threat, i.e., losers of globalization. So, basically, losers of globalization will want to vote for parties who are not in favor of globalization because they don’t like what globalization brings. Kriesi et al. argue that “European integration can also be seen as special cases of the more general phenomenon of globalization”.[21] Therefore if this situation is considered in the context of the European Union, these types of parties are classified as Eurosceptic.

As noted above, far-right parties tend to be Eurosceptic. Here we can add that the common goal of the far-right is “to protect national sovereignty from globalizing forces, which they see as a threat to each nation-state’s independence and right to self-determination.”[22] So, far-right parties also do not have a positive attitude towards globalization. Globalization is considered a threat to national sovereignty by the far-right. Therefore, it will not be surprising that the people who don’t like the idea of globalization and correspondingly have a negative attitude towards European integration support Eurosceptic far-right parties.

Here it needs to be highlighted that Eurosceptic parties can be both far-right and far-left. However, this explanation is more suitable for the far-right because it mainly considers the cultural dimension of integration. Far-left Euroscepticism focuses more on the economic dimension of European integration. Kriesi et al. argue that losers of globalization have the feeling of a national community[23]. In line with that, McLaren explains one of the main drivers of mass level Euroscepticism as the perception of the EU as a threat to national identity and national sovereignty[24]. As noted above, nationalism is one of the core ideologies of the far-right. So, in line with that ideological characteristic, it would not be surprising that the far-right is not in favor of the notion such as cultural diversity or supranationalization that European integration brings. Therefore, here we can conclude that the losers of globalization tend to vote for far-right parties because their main concerns are more compatible with the ideological features of the far-right instead of the far-left.

4. THE EUROSCEPTIC FAR-RIGHT IN EUROPE TODAY

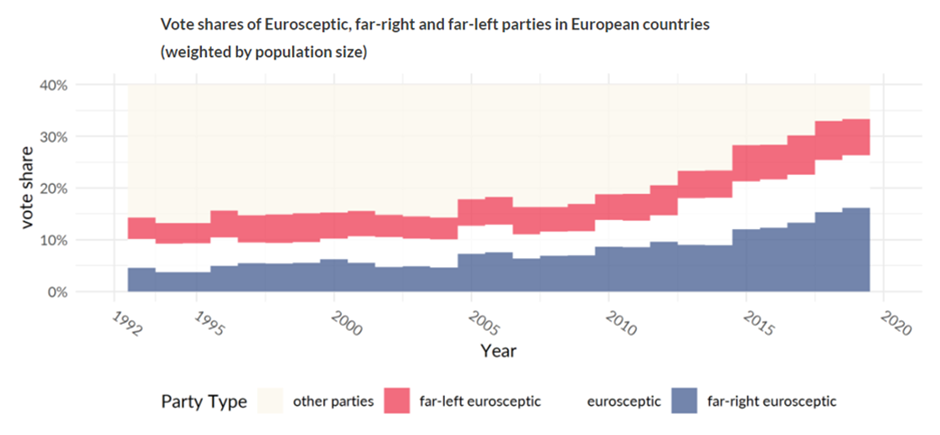

In order to better understand the current role of far-right parties in European politics, in this section, the data that shows the vote share of Eurosceptic parties provided by PopuList will be used. In addition to that, to prove the rising role of far-right parties in the EU, the last two European Parliament elections held in 2014 and 2019 will be discussed.

Now let’s start with examining the overall situation of far-right Eurosceptic parties in Europe. From the figure below, it can be seen that there has been an important success of Eurosceptic parties over the years. They increase their vote shares year by year and become an integral part of European party politics. Also, among the Eurosceptic parties, the significant success of far-right Eurosceptic parties can be seen. According to the latest 2019 data provided by PopuList, far-right Eurosceptic parties made up almost half of the total percentage of the vote share of Eurosceptic parties.

Figure 2: Shares of Eurosceptic, far-right, and far-left parties' votes weighted by population size[25]

Here one point needs to be highlighted. It would be wrong to say that the far-right has dominance in national elections. Generally, they are not powerful enough to gain a majority in the parliament. However, it can be seen that many far-right parties in Europe participate in government coalitions. This increases the policy-making capacity of the far-right and enables them to be directly involved in the agenda-setting process. In this way, they can influence the creation of policies. It can be seen that the policy effect of the far-right is not the same in all areas. For example, with respect to economic policies, there is no common ground that all far-right parties agree on. Therefore, it can be said that the economy is not a priority for the far-right. However, in some policy areas, such as the immigration and integration process specifically, the far-right can create a huge impact. So, here it can be concluded that the more votes these parties get, the more likely they will be in coalitions. Thus, while their influence on the agenda-setting increases, they are more likely to implement the policies they want in line with their Eurosceptic views.

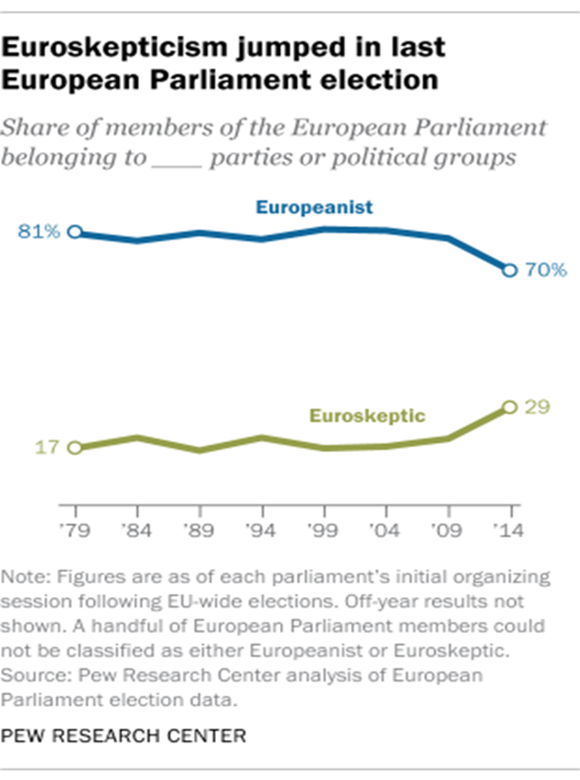

Now, let’s have a look at the 2014 and 2019 EP elections. First of all, the results of the European Parliament elections are very important because it is based on the democratic participation of all EU citizens. It gives voice to EU citizens to form the features of the EU. Also, it provides insights for general public opinion towards the EU. This rise of Euroscepticism, in general, can negatively affect the future of European Integration. Since the EP is the legislative body of the EU, increasing the presence of Eurosceptic groups in the EU can create problems. From the figure below, it can be seen that the gap between Europeanists and Eurosceptics decreased in the European Parliament over the years.

Figure 3: Share of members of the EP[26]

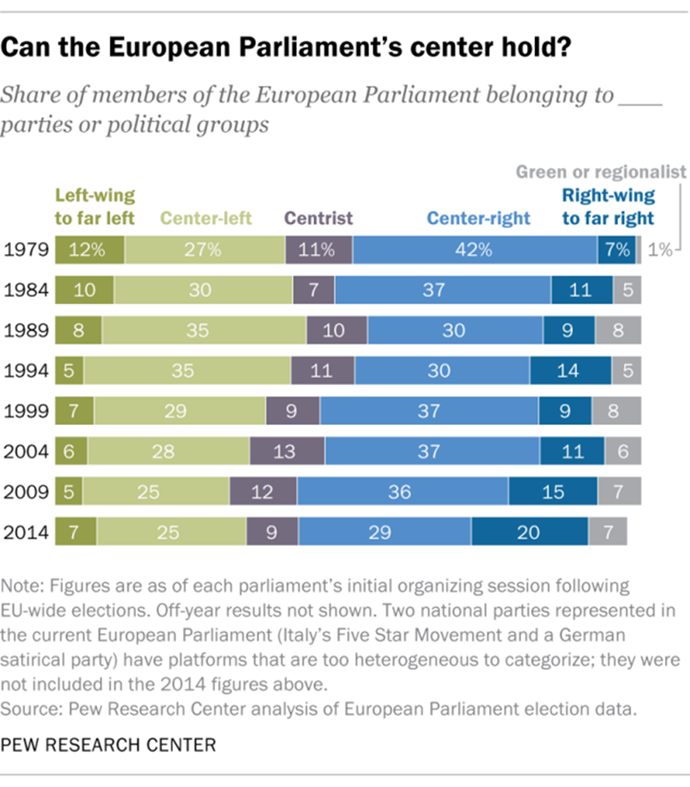

Of course, Eurosceptic parties not only consist of far-right ones, but this paper focuses on far-right parties rather than far-left ones because from the figure below, it can be seen that the vote share of the far-right increased significantly over the years. However, such a significant increase cannot be observed in the far-left.

Figure 4: European Parliament political groups[27]

In the 2019 EP election, Eurosceptics preserved the success that they made in the 2014 EP elections. Right-wing populist parties obtained huge electoral success. In line with this, Brack argues that the 2019 EP elections show that Euroscepticism has become a definite and usual part of European politics[28].

With the latest developments, the effect of far-right Eurosceptic parties on the process of EP decision-making can be expected to increase. However, besides the significant success of far-right Eurosceptic parties and Euroscepticism in general, there are still problems. For example, Brack mentions that “Mainstream politicians do not want to cooperate with Eurosceptics or let them have any kind of influence.”[29] She also suggests that there is not any effective collaboration between far-left and far-right Eurosceptic parties. Also, even the patterns of Eurosceptic opposition of far-right parties are similar.

It is not possible to talk about one single way of far-right Euroscepticism. In this respect, Vasilopoulou explains three patterns of radical right Euroscepticism as rejecting, conditional and compromising patterns. Rejecting category mainly suggests that power should shift back from supranational governance to nation-state and claims the necessity of withdrawal from the EU. Secondly, conditional patterns argue that the EU needs to be governed by intergovernmental institutions rather than supranational ones. Lastly, for compromising Euroscepticism, European integration is not essential, but it accepts that this integration provides some advantages to the member states[30]. In the context of conceptualization, while Front National adopts rejecting Euroscepticism, Lega Nord adopts a conditional pattern. Here we can conclude that there is no one single pattern of far-right. However, Vasilopoulou argues that the common point with respect to far-right Euroscepticism is that far-right parties consider the EU as a threat to national sovereignty[31].

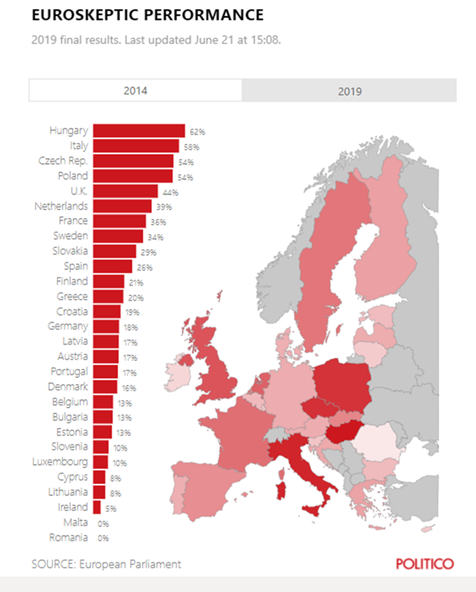

Now, the far-right Euroscepticism will be discussed more specifically by analyzing different parties from different members of the EU. Our cases will be Front National from France and Lega Nord from Italy. The reason these countries were chosen is that according to the data below, their Eurosceptic performance is quite high.

Figure 5: Eurosceptic performance[32]

FN from France and Lega Nord from Italy was chosen because these parties are very important far-right parties. The success of these parties can be seen in the 2019 EP elections. Both of the parties became the first party in their country.

4.1 Front National from France

Front National has been an important far-right Eurosceptic party in France since 1972. So it is a long-established and influential party in French politics. Since 2011, the party has been ruled by Marine Le Pen, who is quite a controversial figure. Especially about the EU, she uses radical discourse.

With respect to the general position of FN to the EU, Vasilopoulou claims that FN adopts a rejecting attitude. They are not in favor of the idea of cooperation. They are very skeptical about EU Treaties[33]. In line with this, they discuss the probability of withdrawal from the EU. For example, during the 2017 presidential election campaign, the leader of FN Le Pen mentioned the possibility of an exit referendum if she is elected. Ivaldi analyzes FN Presidential manifestos between the years 2002 and 2017. This study explains that since then, FN decisively supports the idea of Europe of independent nations and highlights the necessity of exiting the Schengen area[34]. Moreover, they always want to restore national sovereignty. He also argues that “FN has essentially channeled European crises into its established Eurosceptic framework to mobilize a wide range of cultural, economic, and political issues and grievances about the EU.”[35]

Day by day, the usage of social media by politicians is increasing. The far-right commonly use social media tools in order to express their ideas and mobilize the masses. Social media is especially important for the far-right because it enables them to reach more people. At that point, Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripolles argue that “the consolidation of digital media has played a key role in the circulation of populist messages to a large number of people. Such messages have questioned the political and legitimacy terms of the European Union, leading to the ideal scenario of Euroscepticism.”[36]

In this respect, FN is not an exception. Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripolles investigate how Front National frames its communication strategies with respect to Euroscepticism by analyzing its tweets during the 2019 EP election campaign[37]. In the tweets of FN, it can be seen that they harshly criticize the technocratic institution structure of the EU and question the legitimacy of the European Council. Also, with regards to immigration, FN adopts a very negative attitude and highlights the importance of borders. They associate immigration with terrorism. There is a strong division between us (French people) vs. them (immigrants). They mention the negative effects of immigration, and they defend the priority of French interests. In the light of these tweets, FN uses social media “to generate fear and insecurity among citizens and present themselves as the only political option that will protect them from immigration and its consequences”.[38]

Therefore, it can be said that the most sensitive issue for the FN is national sovereignty and border control. FN commonly blames the EU and its technocratic decision-making structure for the bad situation in France. “The Front National argues that under the increasing powers of globalization the state cannot perform its primary purpose, which is to protect the culture of France, because of its suppression of national borders.”[39] The emphasis on identity can be easily seen in the Euroscepticism of FN.

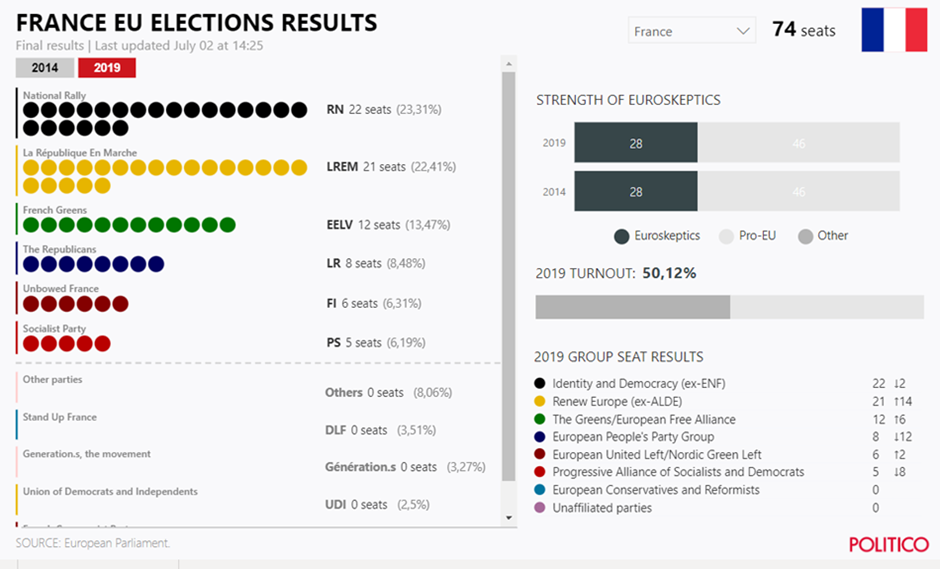

Figure 6: France EP Results 2019[40]

The electoral results of FN in the 2019 EP elections can be considered a huge success. With gaining 28 seats and becoming the first party in France, FN consolidated its role in both French politics and in the EP in general as an important far-right Eurosceptic party.

4.2 Lega Nord from Italy

Lega Nord is an influential far-right party in Italy. It was founded in 1989. Originally the party emerged as a regional party, and its initial name was Lega Nord. The party has been transformed by its new leader Matteo Salvini. In the 2018 elections, the party gained huge success and became the 3rd party in Italy.

With regards to the pattern of EU opposition, Vasilopoulou argues Lega Nord adopts a conditional one[41]. In this respect, they don’t have the willingness to leave the EU, and they are not against the idea of cooperation. However, they have problems with how the EU is practiced today.

Just like all other far-right parties, Lega Nord actively uses social media, especially Facebook and Twitter. The powerful leader of the party, Matteo Salvini, is very popular on social media. Currently, he has 5 million followers on Facebook. Therefore, social media is a very influential communication for Lega to spread the party’s ideas.

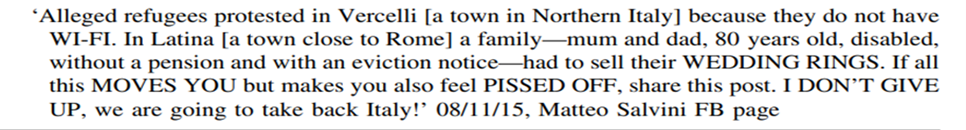

Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripolles also investigate how Lega Nord frames its communication strategies with respect to Euroscepticism by analyzing its tweets during the 2019 EP election campaign[42]. They argue that Lega Nord mentions the issue of immigration frequently. Their leader Salvini argues that immigrants create insecurity in the country. “The Lega Nord manifest a much more restrictive and even xenophobic attitude that defends the prohibition of immigrants entering Italy.”[43] They even propose the establishment of a wall to prevent the entrance of immigrants into the country. It is obvious that Lega Nord demands a solution to the immigration issue. Also, they highlight the importance of traditional values and their religion. Let's have a look at a post that Salvini posted on his Facebook page.

Figure 7: Mateo Salvini Facebook Post[44] (Bobba, 2018, p.18)

This example shows how Lega Nord uses an angry frame towards the situation. Here it can be seen how the notion of national sovereignty is important for them. Just like FN, national sovereignty and border control are vitally important for Lega Nord.

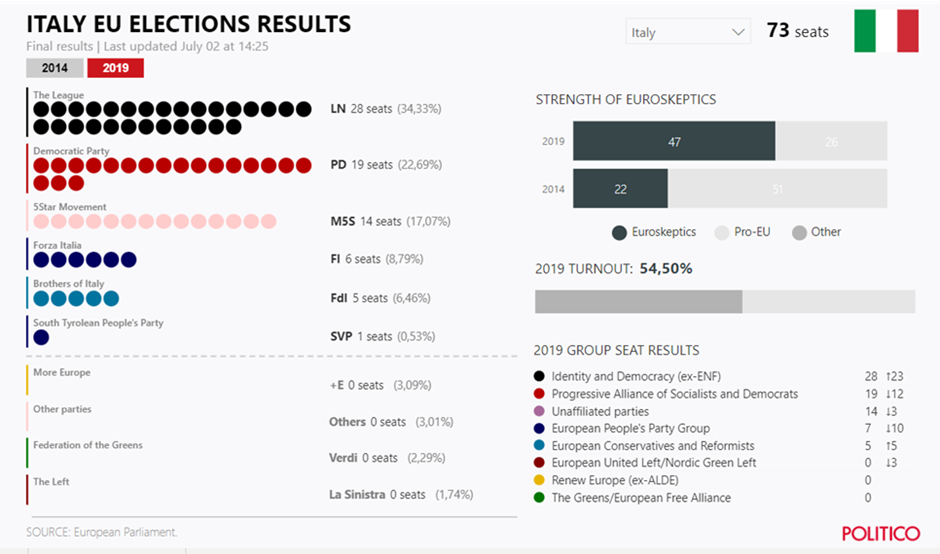

Figure 7: Italy EP Elections 2019[45]

In the last EP elections held in 2019, the party gained important success and became the first party in Italy with 28 seats and further increased its importance in Italian politics.

5. CONCLUSION AND DISCUSSION

To conclude, there is a significant increase of far-right parties in the politics of Europe. This increase also brings the rise in Euroscepticism. As noted above, far-right parties tend to be Eurosceptic. In line with their ideological features, they are not satisfied with the results of globalization and, more specifically, the EU. The main emphasis of the far-right is on national sovereignty. They are against any kind of development that will restrict national sovereignty. This feature of far-right Euroscepticism can be seen in the examples of FN and Lega Nord.

FN and Lega Nord are two parties to do so successfully. As Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripolles analyzed in their study, if the position of FN and Lega Nord with regards to EU is compared, a couple of similar points can be identified[46]. First of all, they both define the problem as a loss of sovereignty. They both highlight the importance of national security and, specifically, the borders. Lastly, what they offer is a total re-foundation of the EU. On the other hand, they differ in their pattern of Euroscepticism. Vasilopoulou (2011) argues that while FN adopts rejecting pattern, Lega Nord uses a conditional one[47].

Far-right parties also have the ability to affect the future of European integration. As noted above, they can participate in government coalitions and become influential in the policy-making process, especially in the areas such as immigration. Moreover, with their increasing presence in the EP, their impact on the decision-making of the EU is getting more and more important. All of these developments demonstrate that far-right influence in EU politics is indisputable.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Alonso-Muñoz, Laura, and Andreu Casero-Ripolles. “Populism Against Europe in Social Media: The Eurosceptic Discourse on Twitter in Spain, Italy, France, and United Kingdom During the Campaign of the 2019 European Parliament Election.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, August 7, 2020. https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3694640.

Bobba, Giuliano. “Social Media Populism: Features and ‘Likeability’ of Lega Nord Communication on Facebook.” European Political Science 18 (January 22, 2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0141-8.

Brack, Nathalie. “Towards a Unified Anti-Europe Narrative on the Right and Left? The Challenge of Euroscepticism in the 2019 European Elections.” Research & Politics 7, no. 2 (April 1, 2020): 2053168020952236. https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168020952236.

Chirinos, Ella Adriana. “‘When in France, Do as the French Do!’: The Front National and the European Union; A Battle for the Preservation of French Culture.” Mapping Politics 9, no. 0 (September 11, 2018). https://journals.library.mun.ca/ojs/index.php/MP/article/view/1923.

“Contesting the EU in Times of Crisis: The Front National and Politics of Euroscepticism in France - Gilles Ivaldi, 2018.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0263395718766787.

Pew Research Center. “‘Euroskeptics’ Are a Bigger Presence in the European Parliament than in Past.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/22/euroskeptics-are-a-bigger-presence-in-the-european-parliament-than-in-past/.

Grande, Edgar, Hanspeter Kriesi, Martin Dolezal, Romain Lachat, Simon Bornschier, and Timotheos Frey, eds. “Globalization and Its Impact on National Spaces of Competition.” In West European Politics in the Age of Globalization, 3–22. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790720.002.

Hooghe, Liesbet, and Gary Marks. “Sources of Euroscepticism.” Acta Politica - ACTA POLIT 42 (July 1, 2007): 119–27. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500192.

“In Graphics: How Europe Voted – POLITICO.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.politico.eu/article/how-europe-voted-election-2019-parliament-results/.

Lipset, Seymour Martin, Stein Rokkan, and Immanuel Maurice Wallerstein. Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives. New York: Free Press, 1967.

Martin, Pierre. “Resumen.” Revue internationale de politique comparee 14, no. 2 (December 14, 2007): 263–80.

Mclaren, Lauren. “Explaining Mass-Level Euroscepticism: Identity, Interests, and Institutional Distrust.” Acta Politica - ACTA POLIT 42 (August 1, 2005). https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500191.

Mudde, Cas. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492037.

———. The Far Right in America. London: Routledge, 2017. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315160764.

Mudde, Cas, and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Populism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.veryshortintroductions.com/view/10.1093/actrade/9780190234874.001.0001/actrade-9780190234874.

Pirro, Andrea L. P., and Stijn van Kessel. “United in Opposition? The Populist Radical Right’s EU-Pessimism in Times of Crisis.” Journal of European Integration 39, no. 4 (June 7, 2017): 405–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2017.1281261.

Taggart, Paul, and Aleks Szczerbiak. “Parties Positions and Europe: Euroscepticism in the EU Candidate States of Central and Eastern Europe,” January 2001.

The PopuList. “The PopuList,” February 24, 2020. https://popu-list.org/explore-data/.

Vasilopoulou, Sofia. “European Integration and the Radical Right: Three Patterns of Opposition.” Government and Opposition 46, no. 2 (ed 2011): 223–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2010.01337.x.

———. Far Right Parties and Euroscepticism: Patterns of Opposition, 2018.

———. “The Radical Right and Euroskepticism.” The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, April 26, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190274559.013.7.

“Vote 2014 Election Results for the EU Parliament UK Regions - BBC News.” Accessed March 4, 2022. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/events/vote2014/eu-uk-results.

Werts, Han, Peer Scheepers, and Marcel Lubbers. “Euro-Scepticism and Radical Right-Wing Voting in Europe, 2002–2008: Social Cleavages, Socio-Political Attitudes and Contextual Characteristics Determining Voting for the Radical Right.” European Union Politics 14, no. 2 (June 1, 2013): 183–205. https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512469287.

[1] “Vote 2014 Election Results for the EU Parliament UK Regions - BBC News,” accessed March 4, 2022, https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/events/vote2014/eu-uk-results.

[2] Cas Mudde, The Far Right in America (London: Routledge, 2017), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315160764., 1.

[3] Mudde, 2

[4] Cas Mudde, Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511492037.

[5] Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser, Populism: A Very Short Introduction, Populism: A Very Short Introduction (Oxford University Press), accessed March 4, 2022, https://www.veryshortintroductions.com/view/10.1093/actrade/9780190234874.001.0001/actrade-9780190234874., 6

[6] Sofia Vasilopoulou, Far Right Parties and Euroscepticism: Patterns of Opposition, 2018., 5

[7] Liesbet Hooghe and Gary Marks, “Sources of Euroscepticism,” Acta Politica - ACTA POLIT 42 (July 1, 2007): 119–27, https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500192.

[8] Sofia Vasilopoulou, “European Integration and the Radical Right: Three Patterns of Opposition,” Government and Opposition 46, no. 2 (ed 2011): 223–44, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1477-7053.2010.01337.x., 224

[9] Paul Taggart and Aleks Szczerbiak, “Parties Positions and Europe: Euroscepticism in the EU Candidate States of Central and Eastern Europe,” January 2001.

[10] Han Werts, Peer Scheepers, and Marcel Lubbers, “Euro-Scepticism and Radical Right-Wing Voting in Europe, 2002–2008: Social Cleavages, Socio-Political Attitudes and Contextual Characteristics Determining Voting for the Radical Right,” European Union Politics 14, no. 2 (June 1, 2013): 183–205, https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116512469287., 187

[11] Andrea L. P. Pirro and Stijn van Kessel, “United in Opposition? The Populist Radical Right’s EU-Pessimism in Times of Crisis,” Journal of European Integration 39, no. 4 (June 7, 2017): 405–20, https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2017.1281261.

[12] Vasilopoulou, “European Integration and the Radical Right.”

[13] Mudde, Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe., 164

[14] Werts, Scheepers, and Lubbers, “Euro-Scepticism and Radical Right-Wing Voting in Europe, 2002–2008.”

[15] Werts, Scheepers, and Lubbers., 196

[16] Pirro and van Kessel, “United in Opposition?”, 407

[17] Seymour Martin Lipset, Stein Rokkan, and Immanuel Maurice Wallerstein, Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross-National Perspectives (New York: Free Press, 1967).

[18] Edgar Grande et al., eds., “Globalization and Its Impact on National Spaces of Competition,” in West European Politics in the Age of Globalization (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2008), 3–22, https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511790720.002.

[19] Pierre Martin, “Resumen,” Revue internationale de politique comparee 14, no. 2 (December 14, 2007): 263–80.

[20] Grande et al., “Globalization and Its Impact on National Spaces of Competition.”

[21] Grande et al., 3

[22] Vasilopoulou, Far Right Parties and Euroscepticism., 5

[23] Grande et al., “Globalization and Its Impact on National Spaces of Competition.”

[24] Lauren Mclaren, “Explaining Mass-Level Euroscepticism: Identity, Interests, and Institutional Distrust,” Acta Politica - ACTA POLIT 42 (August 1, 2005), https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ap.5500191.

[25] “The PopuList,” The PopuList (blog), February 24, 2020, https://popu-list.org/explore-data/.

[26] “‘Euroskeptics’ Are a Bigger Presence in the European Parliament than in Past,” Pew Research Center (blog), accessed March 4, 2022, https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/05/22/euroskeptics-are-a-bigger-presence-in-the-european-parliament-than-in-past/.

[27] “‘Euroskeptics’ Are a Bigger Presence in the European Parliament than in Past.”

[28] Nathalie Brack, “Towards a Unified Anti-Europe Narrative on the Right and Left? The Challenge of Euroscepticism in the 2019 European Elections,” Research & Politics 7, no. 2 (April 1, 2020): 2053168020952236, https://doi.org/10.1177/2053168020952236.

[29] Brack., 6

[30] Vasilopoulou, “European Integration and the Radical Right.”

[31] Sofia Vasilopoulou, “The Radical Right and Euroskepticism,” The Oxford Handbook of the Radical Right, April 26, 2018, https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780190274559.013.7.

[32] “In Graphics: How Europe Voted – POLITICO,” accessed March 4, 2022, https://www.politico.eu/article/how-europe-voted-election-2019-parliament-results/.

[33] Vasilopoulou, “European Integration and the Radical Right.”

[34] “Contesting the EU in Times of Crisis: The Front National and Politics of Euroscepticism in France - Gilles Ivaldi, 2018,” accessed March 4, 2022, https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.1177/0263395718766787.

[35] “Contesting the EU in Times of Crisis: The Front National and Politics of Euroscepticism in France - Gilles Ivaldi, 2018.”, 281

[36] Laura Alonso-Muñoz and Andreu Casero-Ripolles, “Populism Against Europe in Social Media: The Eurosceptic Discourse on Twitter in Spain, Italy, France, and United Kingdom During the Campaign of the 2019 European Parliament Election,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, August 7, 2020), https://papers.ssrn.com/abstract=3694640., 1

[37] Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripolles.

[38] Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripolles., 7

[39] Ella Adriana Chirinos, “‘When in France, Do as the French Do!’: The Front National and the European Union; A Battle for the Preservation of French Culture,” Mapping Politics 9, no. 0 (September 11, 2018), https://journals.library.mun.ca/ojs/index.php/MP/article/view/1923., 12

[40] “In Graphics: How Europe Voted – POLITICO.”

[41] Vasilopoulou, “European Integration and the Radical Right.”

[42] Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripolles, “Populism Against Europe in Social Media.”

[43] Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripolles., 6

[44] Giuliano Bobba, “Social Media Populism: Features and ‘Likeability’ of Lega Nord Communication on Facebook,” European Political Science 18 (January 22, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0141-8.

[45] “In Graphics: How Europe Voted – POLITICO.”

[46] Alonso-Muñoz and Casero-Ripolles, “Populism Against Europe in Social Media.”

[47] Vasilopoulou, “European Integration and the Radical Right.”

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

AVİM’de tüm yıl boyunca Uygulamalı Eğitim Programı (UEP) devam etmektedir. Avrasya bölgesine dair çalışmalara ilgi duyan adaylar, bu programa kısa veya uzun dönemli katılımlar için başvuruda bulunabilirler.

Bu sayfada AVİM Uygulamalı Eğitim Programı katılımcılarının hazırlamış oldukları raporlardan bazı örnekler yayınlanmaktadır. Yayınlanan raporlar yalnızca yazarlarının görüşlerini temsil etmektedir ve bu raporların AVİM için bağlayıcılığı bulunmamaktadır.

The Traineeship Program at AVİM is offered throughout the year. Applicants are expected to possess a high interest in Eurasian affairs. Applications for the program may be made either for the short or the long term.

Some examples of the reports prepared by Traineeship Program participants are published on this page. These reports solely reflect the views of their authors and are not binding for AVİM.