Ali Sinan GÜLTEKİN

Traineeship Program Participant

Abstract: President of Belarus Alexander Lukashenko has succeeded in becoming the longest-serving leader in Europe, labeled in Western media as ‘the last dictator in Europe’. Belarus, which gained independence on July 27, 1990, appears to be an exceptional example to those post-Soviet countries struggling to constitute their own identities. This identity depression is crucial to shedding light on contemporary Belarusian politics. Impasses, for instance, which the Belarusian Popular Front used to go through during the glasnost era, overlap with those which pro-Western and liberal opposition has been experiencing afterwards. While this opposition has some continuities in itself, disruptions and changes in time and also contradictions arising from dialectics have given birth to contemporary dissidence. An opposition cannot be reduced to any one of these attributes, but must be considered a totality of them. Elucidating these continuities and contradictions, unlike some reductionist accounts, could provide a projection about Belarus’ today and future. It seems impossible to make sense of Belarusian politics without considering upon which class interests and historical conjuncture the opposition has been based. This report strives to put Belarusian identity which has dicotomically been constructed in relation to that of Russia, in its historical context and clarify further what kind of a ‘counter historical bloc’ the opposition seeks to establish so as to give meaning to symbols, words and values in political discourse. Then, it is going to discuss at-length how these super-structural deficiencies are essential to establish a historical bloc which lead the opposition to a fundamental obscurity.

Key Words: Belarus, Alexander Lukhasenko, Belarusian Democracy Movement

AVİM’s Note: This report was prepared prior to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine that began on 24 February 2022. As such, Belarus is beginning to find itself in a rapidly changing geo-political landscape in comparison to the time when this report was prepared.

INTRODUCTION

Today’s liberal narratives tend to evaluate Belarusian politics as the sphere of a struggle between authoritarianism and democracy. Yet, this sort of assessment may be reductionist and misleading. This would be the case because the material base is neglected, but also because the current political struggle in Belarus is, in some sense, abstracted and detached from a historic explanation. There appears uncertainty regarding several extra-historical aspects. Thus, a structural and critical explanation is necessary to comprehend the trajectory and framework of Belarus. This report will attempt to analyse the origins as well as the current opportunities of the opposition against the ‘Europe’s last dictator’ Alexander Lukashenko. In so doing, first, it will inspect the history of the country from the era of Kyivan Rus’ to 1991 in order to make sense of the current struggle over symbols and origins. Second, the opposition’s discourse in concealing its class consensus will be clarified to understand the superstructure level of Belarus. And lastly, the opposition’s future projection and the paradox of Belarusian politics will be critiqued.

A BRIEF HISTORY OF BELARUS BEFORE 1922

The Belarusian region, which is located at the crossroads of today’s Russia to the east, Poland to the west, Lithuania to the north and Ukraine to the south, is known to have a long history of settlement. The name ‘Belarus’ comes from the expression “Belaya Rus” which means “White Rus”[1]. By the early stages of 6th century, Slavic tribes began to dominate the inhabited areas of the region[2]. From then on, Slavs have been the chief residents.

The Kyivan Rus’, which is accepted as the cultural origin by Russians, Ukrainians, and Belarusians, controlled what is now modern day Belarusian territory in the 9th-13th centuries. However, this polity never had ‘state’ mechanisms, instead, it operated as a loose unity of Slavic tribes at the time. Although some describe the Kyivan Rus’ as the first state established by Russians, the nationalist narrative of Belarus claims that Belarusians came from the principality of Polatsk[3]. Given the unprecedented Great Mongol incursions in the 13th century into lands of Eastern Europe, the principality of Polatsk, in some sense, was the least affected part of Kyivan Rus’. However, due to the collapse of that loose union and a dangerous and chaotic environment in what is now modern-day Belarusian territory, those principalities sought protection from the Great Duchy of Lithuania[4]. That is why the historical course of the Belarusian and Ukrainian people took separate paths. While north-eastern Slavic peoples began living under the rule of Mongolian Empire, their brethren in the West were a part of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Consequently, up to the nineteenth century, the territory of Belarus had been a space for the competition for territorial control between the Russian Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. As it is explained at-length in the next chapters, symbols inherited from the period of the Commonwealth are prominently used in the flags by dissidents in Belarus.

The modern-day Belarusian territory, thus, had been taken over sequentially by the Russian Empire and the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth. Indeed, it is quite observable today that, although official narratives of Belarus consider its society as Eastern Slavic, there are some societal features inherited from Western Slavs, i.e., Poles[5]. In interpreting this period of history, the national narrative of 1990s Belarus differed from that of Belarus SSR. The impact of the ‘epistemological break’ from the Russian-centered narratives writing is best illustrated in history: the war of 1654-55 between Russia and the Commonwealth of Poland, for instance, started being named as an ‘annexationist’ act of aggression of Russia, which is just the opposite to the previous interpretation that had perceived the war as an effort of ‘liberating’ Belarus[6].

In contrast to the Ukrainian experience, Belarus had never enjoyed even a short period of independent political life until March 1918. Following the Bourgeois Revolution in March and the Bolshevik Revolution in November 1917, the Belarusian elites, i.e., small businessmen, landowners, etc., decided to remain neutral and chose a policy of wait-and-see, unlike the Ukrainians who considered the breakout of the crisis as an opportunity for independence. After the signing of the Brest-Litovsk Treaty between Russia and the German Empire on 3 March 1918, a would-be independent state, named the Belarusian People’s Republic, in Belarus was established. Yet, the lifespan of this ‘artificial’ state was limited due to the Brest-Litovsk Treaty, because there was no popular demand for Belarusian sovereignty. Additionally, this entity functioned not as a sovereign state, but as a German stronghold[7]. Following the German withdrawal from the First World War (WWI) and the emergence of a danger of revolution in November 1918, the peace treaty was declared null and void and the Red Army’s offensive into the territories previously occupied by the Germans began. Consequently, after the foundation of a Bolshevik state, Belarus became one of the four Soviet republics which signed the Declaration and Treaty on the Creation of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR)[8].

BELARUSIAN SSR: THE FORMATION OF THE BELARUSIAN IDENTITY

In the aftermath of the Second World War (WWII), Belarus had been razed to the ground and lost a quarter of its population[9]. That is why the plan of a rapid construction began, owing to funds coming from Moscow. It is undoubtedly true that, by virtue of the emergence of satellite states of the USSR between Belarus and the Western Bloc, Belarus was finally able to enjoy a period in which it was not a subject of power competition. Thus, it was much easier to invest in the industrialization of the region. According to figures, by 1989, Belarus had become the chief success of the Soviet Union, leading 15 other states in the Union in achieving an increase of individual wealth[10]. It is thus no wonder why Alexander Lukashenko has utilized the ‘Sovietization’ discourse unlike other ex-Soviet republics, since the term ‘Soviets’ has a positive connotation to the Belarusian people.

CORRUPTION: A CAUSE OR A RESULT?

The USSR, after a drawn-out existential crisis resulting from several causes such as rampant corruption, an expensive arms race due to US President Ronald Reagan’s desire to prolong the Cold War in the 1980s, a mentally and economically costly war in Afghanistan which lasted for a decade, and the materialization of statecraft contradicting with Marxist tradition of thought, finally came to its end in December 1991. Even though the main reason behind this collapse remains a fundamentally controversial topic among scholars, i.e., depending on what one’s perspective is, where one looks at and which indicators one finds there, at the time of the USSR’s disintegration, the peoples of the USSR mostly agreed on the idea that the disintegration had been caused by the corruption that had become ingrained within the Soviet society and polity[11].

Conversely, as mentioned above, the situation was quite the opposite for the Belarusians, since they had enormously benefited from the achievements of the USSR throughout the Cold War. Up to 1991, giant industrial complexes owned by the state had not only provided jobs to the Belarusians, but also created a social security sphere for individuals to endure hardships. Similar to the experiences of proletarianized masses of the capitalist industrialization’s first generation during the early decades of 19th century, the working masses of Belarus, after the USSR’s disintegration, started to suffer from the loss of previously obtained social rights granted by a state-socialist economy[12]. After the USSR’s disintegration, in order to make former socialist economies integrated into the global capitalist market, the technocrats of the world’s leading financial organizations, e.g., International Monetary Fund (IMF) and World Bank (WB), agreed upon a ‘remedy’ that consisted of a list of economic reforms aiming to dismantle state subsidies. And Belarus was no exception. Following independence, from 1991 to 1994, Belarusian Head of State Stanislau Sushkevich and Prime Minister Vyacheslav Kebich did not hesitate to sell state plants and comply sincerely with this ‘shock therapy’.

When one looks at the case of Russia’s economic transformation after the USSR’s disintegration, it is quite apparent that the abundant wealth of the oligarchs, who had had bureaucratic professions which afterwards granted them absolute privilege in accumulating capital in the crucial conditions of the capitalist free market, was a product of rents of extractive natural sources, be it oil or natural gas[13]. The scenario was rather contradictory for Belarus, where there was only one profitable, rentable source: potassium. Therefore, in contrast to the course of privatization in Russia, because Belarus did not have adequate internal sources to accumulate capital, the emergent oligarchs were rather mostly ‘outsiders’, especially Russians. Yet, this fact might be misleading, since Vladimir Putin of Russia came to power in 2000, and only a few Russian oligarchic formations, namely Gazprom, had been permitted to operate in Belarus[14]. The Belarusians’ grievances, stemming from the loss of social security, brutal market conditions and corruption, would be a perfect backdrop for a ‘populist’, independent, ‘neither leftist nor rightist’ president as A. Lukashenko[15]. Preceding 1991, Lukashenko had served as a manager of a state farm, and then as a member of the Soviet Army. Following the elections for the Supreme Council of the Republic of Belarus in 1991, he was reputed to be a stubborn opponent of corruption.[16] Consequently, Lukashenko’s main discourse for the presidential election in 1994 was based on a war against corruption, market brutality, and the ‘Westernization’ of Belarus.

The period of 1991-94 might also lead us to think of the process of forming a national identity after the independence. In this regard, it is essential to look at the words of the first ruling elites of the independence period. The most remarkable thing that precisely accounts for national identity formation in Belarus is that neither Kebich nor Sushkevic was willing to speak Belarusian, even though Belarusian was both their mother tongue and the state’s official language. As Zaprudnik puts it, “Kebich used to behave as if he had been appointed by Moscow.”[17] The primacy of Russian, either in daily usage or in the official domain, was not a controversial topic either at the state or public levels. Although Lukashenko was in a race against those who had been ruling the country from 1991, his presidential campaign mainly depended on economic rather than identity issues. Neither did Lukashenko think that Belarusian had to be the sole official language, which is why, after getting into the office, his call for a referendum in 1995 included a demand to add Russian as the second official language, which was approved by four out of five Belarusians[18].

Lukashenko’s 1994 success did not come as a surprise for those who thought that Belarus’ socio-economic and political systems were on the verge of vanishing because of would-be reforms implemented without public consent. There used to be an oligarchic and non-consensual regime between 1991-94. The civil society seemed to be separated into two solidified sides: on the one hand pro-Westerners and liberals whose economic ideas were in power, and on the other, the statist and conservative political structure that reluctantly complied with IMF’s remedy. The subsequent political schedule under the government of Lukashenko was seen as a counter-revolution in the name of neo-Soviet economic policy against the capitalist market system after the presidential election of 1994[19]. Thus, it was argued by the former Belarusian deputy minister of foreign affairs that this economic policy had ideological ingredients based on a conscious choice of identity, i.e., economically close relations with Russia and bearing a resemblance to the Soviet economy[20].

A STRUGGLE OVER SYMBOLS AND THE INTENSIFICATION OF LUKASHENKO’S POWER

Following the independence and the endorsement of a new constitution, Belarus’ state symbols were changed to those implying the country’s Lithuanian past and the ‘artificial’ state that was formed under the German invasion in 1918. The newly-adopted flag had also been used by pro-German ‘traitors’ during the Patriotic War of 1941-45. In this regard, along with the economic chaos, the new state’s ideological apparatuses were deficient in the beginning. Lukashenko, being a non-partisan presidential candidate, did not hesitate to mobilize public grievances on these related issues. According to him, the economic chaos and the effort of establishing Belarus’ western roots were absolutely related. However, it must be stated that Lukashenko was a product of the socio-economic problems at the time, not a man who had ‘created’ them in the people’s minds[21].

Due to the Belarusian Popular Front’s[22] (BPF) failure to mobilize masses in the urban centers and fulfill its promises of creating a sovereign nation based on a nation-wide growth of wealth compared to its previous era, Lukashenko profoundly succeeded in establishing a new stage for politics: Protecting people from the brutality of ‘shock therapy’, i.e., capitalism, that plunged neighboring countries, Russia, and Ukraine, into total chaos. He gradually strived to change what had been done in 1991-94: 1) preserving state enterprises that were the biggest job-providers in the country; 2) eliminating ‘alien’ state symbols; 3) establishing deeper relations with former-Soviet republics, particularly Russia.

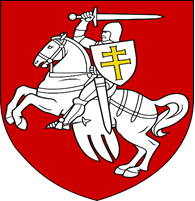

In this regard, in 1995, by virtue of his popularity, Lukashenko confidently proposed a referendum consisting of 4 questions: I) assigning Russian as the second official language; ii) approving the President’s policy of integration with Russia; iii) new state flag and coat of arms; iv) constitutional changes for giving the president the power of elimination of the Supreme Soviets of Belarus in case of systematical violations of the Constitution[23] (see, fig. 1, 2, 3 and 4). In 1996, another referendum, this time regarding the consolidation of the President’s power, was held. Lukashenko was given a wide range of authority that was quite incompatible with democracy, which included the legislature becoming directly subordinated under the rule of president[24]. Additionally, as a result of the approval of the referendum in 2004, the constitutional article which confined the president’s terms in office to two-five years was changed and Lukashenko was enabled to become president for as long as he wishes[25].

Figure 1. Belarusian Coat of Arms, 1991-94[26]

Figure 2. Belarusian Coat of Arms, 1995-present[27]

Figure 3. Belarusian Flag, 1918 and 1991-94[28]

Figure 4. Belarusian Flag, 1995-present[29]

DISSIDENCE AGAINST LUKASHENKO

Following the materialization of the indications of the of the USSR’s collapse in the late 1980s, divergent groups of interests appeared on the scene of politics in Belarus promulgating their views on the future of the country. Although nationalist movements emerged, they lacked popular and intellectual support which was essential in fostering a national state. First, as Hobsbawm puts it, nationalism requires a group of elites whose publications standardize and nationalize, indeed ‘invent’, a dialectic of a language[30]. The Belarusian Popular Front and Belarusian Association of Servicemen movements were far from being adequate examples of this kind, as these movements were not a product of historical dialects but that of the USSR’s leader Mikhail Gorbachev’s glasnost[31]. Additionally, the national cause needs collective traumas, e.g., the German invasion of Belarus in 1941-1944, which can be used in inventing a nation. Yet, the nationalist movements of Belarus were not effective in using WWII in fostering Belarusian identity and this resulted in using symbols recalling collaborators of the foreign invasion. Marples suggests that the Belarusian national identity was mutually structured with Soviet identity by the upsetting experiences of WWII[32]. Consequently, even though dissident symbols may be seen as a reference to the country’s Western roots, these roots themselves have a fundamentally negative effect on the Belarusians’ perception towards the opposition.

Following Lukashenko’s reforms on the constitution, a relatively large protests occurred in 1996-97, named the Minsk Spring[33]. In this regard, the opposition agreed upon some fundamental principles, fostered an umbrella organization, and declared Charter 97 aiming to democratize Belarus’ regime to possess more Western liberal values[34]. The constitutional change in 2004 concerning presidential terms, which paved the way for Lukashenko to serve for unlimited terms, also sparked a rather mild protest. As observed in other post-Soviet republics, there emerged a colour revolution named the Jeans, or Denim[35], Revolution in the aftermath of Lukashenko’s third election victory in 2006. This uprising was followed by those had occurred in Georgia in 2003, Ukraine in 2004, and Kyrgyzystan in 2005. Yet, unlike the others, the Denim Revolution failed. Subsequently, dissidents, although discouraged by the elections and economic crisis, sought to topple Lukashenko and took to the streets in 2010, 2011, and 2017. However, none of them were enough to unseat Lukashenko.

RECENT DEMONSTRATIONS

The recent demonstrations began in the wake of Lukashenko’s sixth victory in the 2020 elections. Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, who ran for presidency in the elections, appeared to be the ‘inherent’ leader of the opposition movement. She decided to become a candidate after her husband, a dissident Youtuber and blogger Sergei Tsikhanouskaya had been arrested by Belarusian authorities prior to the presidential election. He was arrested right after his statement on being a presidential candidate and declaring the ‘Cockroach Revolution’[36]. When Lukashenko announced his victory according to official results, thousands had already taken to the streets to protest the ‘pre-determined’ election[37]. The opposition’s candidate Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya suddenly disappeared and showed up a few weeks later in Lithuania wherein Western-oriented Belarusian opposition has always found institutional support. In addition to providing shelter to dissidents, the Foreign Ministry of Lithuania also accredited the Belarusian opposition with diplomatic recognition[38].

DISCOURSE AND SYMBOLS USED BY OPPOSITION: A WICKED GAME

First, by emphasizing discourse, this report does not refer to a post-structuralist perspective. Rather, one must bear in mind that discourse, or the power of the words, serves as a tool that creates a space for politics under which a class consensus operates. To put it another way, words are prominent tools at superstructure level to produce, exchange and delineate beliefs and values. They are useful means to interpret reality. ‘Nothing is suspended in the air’[39], and nor is political discourse. Studying discourse and symbols can help in shedding light on the components of the opposition’s class consensus.

Sviatlana, for instance, often refers to the EU as a body that encompasses Belarus, i.e., assigning a Europeanness to the Belarusian society. During the ceremony of the Sakharov Human Rights Prize given by the EU, she said “Without a free Belarus, Europe is not fully free either”[40]. Furthermore, she repeatedly calls for Western powers to impose or broaden sanctions on the Belarusian authorities and Lukashenko-backed oligarchs[41]. On 28 May 2021, Ursula Von der Leyen, head of the European Union (EU) Commission, outspokenly promised Sviatlana that the EU would provide a 3 Billion euro aid for post-Lukashenko Belarus under a proposal called ‘the EU Plan for Democratic Belarus.’[42] One can easily notice that her speech is laden with an apparent economic manifest. In so doing, she seeks to render her class interests, which envisage significant benefits through comprehensive relations with the West, the national interest[43]. That is not to say she herself is a physical member of the given class, as she is a teacher and mother of two children of ordinary means. But she is also, in a Gramscian sense, an ‘organic intellectual’ who is a product of the emergent economic class[44].

To put it another way, an existing, albeit limited, relations of production which strive to shift Belarus’ current dominant economic relations from being Russian-oriented to a far more liberal one must create their own ideologues so as to generate consent for their anticipated order in society. It goes without saying that in industrialized countries wherein reside differentiated relations of production and indeed a civil society, taking over mere state apparatus through a bloody resurrection, i.e., through a war of maneouvre as Gramsci puts it, is not a plausible way to build up an alternative order. Instead, a counter hegemonic movement must conduct a war of position, meaning that civil society must be persuaded to join the upcoming new order[45]. Thus, the limited presence of the Western-oriented bourgeoisie in Belarus has engendered its own organic intellectuals, including Sviatlana.

Conversely, classes forming the ‘historical bloc’ that supports Lukashenko’s regime strive to ensure the protection of their prevailing roles in the existing ‘market socialism’ that is based on a model that currently leaves little room for foreign and private investments[46]. This economic model mostly depends on close trade relations with Russia. However, it would be irrational to argue that the economy of Belarus harbouring several oligarchs on the outside of the state-control is a succession of the Soviet model that used to be based completely on state socialism. Even though these few oligarchs have flourished under the wings of the state, it does not mean that Belarus’ regime is oligarchic. On the contrary, with a state that has operations in the biggest and crucial terrains of economy, Belarus ought to be anti-oligarchic to reproduce itself. Indeed, a mode of production in which the absolute majority of the means of production belong to the state cannot be named oligarchic[47]. Perhaps this is why it has been possible for a separate interest group among the rich to emerge, mobilize, and aspire for the government.

OPPOSITION’S FOREIGN TIES

Not surprisingly, the EU and the United States (the US) have been funding the Belarusian opposition since the late 1990s[48]. In this regard, by virtue of a law, the Belarusian government abolished participation in unregistered organizations, undoubtedly, to eliminate mostly Western-backed organizations. While some distinguish between the US funds transferred to financing dissident NGOs and the EU funds transferred to consulting companies[49], in time, both international parties have succeeded in unifying their efforts. As mentioned above, since 2017, the EU has repeatedly announced several aid programs for the Belarusian opposition. This funding reached new levels after the 2020 presidential elections and seems be increasing at an intensified pace[50]. However, this funding has so far failed to topple Lukashenko.

Previously, low accessibility to internet in Belarus had caused the failure of the opposition to promulgate their ideas through society. However, according to World Bank data, the percentage of internet users in the Belarusian population almost tripled, from 16.2% to 54.1%, between 2005-2013[51]. The simultaneous process of the accumulation of foreign funds and increase in the internet usage paved the way for opposition to propagate their views and messages. The uncontrollable nature of the internet has always provided an important backdrop for the opposition[52]. Thus, after 2010, a much more concentrated and effective opposition has emerged in Belarus.

A SHIFT IN POLITICS AFTER THE 2014 UKRAINE CRISIS

It might be argued that Russia has unconditionally been supporting Lukashenko from the beginning given his doubts about the West. Lukashenko has also been accused of Russifying Belarus[53]. Yet, in the aftermath of 2014 Ukraine Crisis, Lukashenko displayed a critical shift in his rhetoric and policy towards Russia and initiated a normalization with the EU by reducing suppression against the opposition[54]. This is because “after Crimea, Belarusian authorities realized the risks of a national identity that has not yet fully formed”[55]. Even though Lukashenko sought to weaken the opposition’s main finance and maintain his authority as much as possible, he was eager to balance Russia with the EU, which made Russia uneasy about this normalization[56]. Lukashenko himself spoke of a ‘soft-Belarusization’ in January 2015[57]. Poshokin upholds this conceptualization and argues that after 2014, Belarusian authorities showed a tendency to regard Belarusian identity as the nation’s existential condition, while Russian identity was regarded as practical[58]. In so doing, Lukashenko fortified his power as he appeared to have refuted the criticisms directed at his close relations with Russia.

This shift was undoubtedly evident in Lukashenko’s rhetoric. For the first time ever, in 2014, he gave a speech in Belarusian[59]. Together with the aforementioned normalization with the EU, he now sought to establish a separate identity laden with a firm discourse of sovereignty. Yet, the process was hampered by several causes and, today, while still persistent to establish a separate Belarusian identity, lacking an international recognition, Lukashenko seems to have relinquished dreams of maintaining a regime balancing between the West and Russia.

AN IMPASSE FOR THE OPPOSITION: FOSTERING A ‘WESTERN’ BELARUSIAN STATE

The opposition’s failure to mobilize a nation-wide movement against Lukashenko stems from several historical and structural reasons. The main cause behind the failure is that symbols and discourse used by the opposition have had an appalling reputation in the minds of the Belarusian people from the very beginning. This flawed set of concepts lead the opposition to fail in converting their specific class interests to a ‘national interest’. Such conversions are what make revolutions possible. First seen during the nationalist movement in the late 1980s and then observable in the dissidence against Lukashenko, the desire to form a separate identity from Russia has led to a ‘disoriented nationalism’. By using Western money and influence outspokenly, the opposition is unable to persuade Belarusians that they are actual members of the society. Rather, these direct foreign aids make it easy for Lukashenko to accuse the opposition of being puppets of the West[60]. That is to say, as mentioned above, neglecting a given society’s collective traumas, e.g., Patriotic War of 1941-45 in the example of Belarus, the opposition seeks to build a ‘nation’ state that is unfamiliar to the nation.

Thus, an independent Belarusian nationality, if there exists such a thing, cannot be taken for granted and the opposition must build it on real-life experiences. On the other hand, the emergent opposition must convince the Belarusian people that a post-Lukashenko and Western-oriented Belarus will become much more liveable. Losing the social rights acquired under Lukashenko is a risk that most of Belarusians seem to be reluctant to take for the sake of liberal democracy. As Žižek puts it, before 1989, Soviet societies ‘had not been aware of the price to live in a risk society’[61]. And Belarusians appeared to be aware of this, as 83 percent of the Belarusians voted in favour of the preservation of the USSR in Gorbachev’s 1991 referendum[62].

Even though official numbers of approval for Lukashenko are quite incongruent with reality, some his opponents and also most scholars deceive themselves by putting trust in internet polls. To exemplify, according to some internet polls, Lukashenko’s approval rating before the 2020 presidential elections was 3%[63]. This number is undoubtedly far from providing accurate information, just like official polls conducted by the government. Thus, discussions about Belarus tend to go back and forth between these two unrealistic poles. Admitting that Lukashenko has lost popular support at an accelerating pace in recent years, yet, these kinds of internet polls that neglect the underpinnings of the regime’s popularity create a deceptive perception and lead them to underestimate Lukashenko.

CONCLUSION

Grasping the insight of the Belarusian opposition must not lead us to run in the circles of an abstract world. As shown above at-length, the power competition in Belarus has connotations of class struggle based on the symbols and words being used, all of which have political implications. On the one hand, there is Lukashenko’s state apparatus and the ‘oligarchs’ whose interests require maintaining the status quo. On the other hand, the opposition consists of the class that attribute the wealth of people to the free market. These people are mostly from the middle class that has flourished in the corners of the existing limited economic system. Thus, the democracy discourse and the demand for a liberal economy are intertwined. Democratic grievances are put forth at the superstructure level, while a demand for a free market takes place at the infrastructure level.

*Photograph: Belarus President Alexander Lukashenko - Andrea Verdelli/Getty Images

BIBLIOGRAPHY

“1996 Human Rights Report: Belarus .” U.S. Department of State, January 30, 1997. https://1997-2001.state.gov/global/human_rights/1996_hrp_report/belarus.html.

“Coat of Arms of Belarus (1991–1995).” Wikimedia Commons. Accessed November 23, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Belarus_(1991).svg?uselang=ru.

“Conclusions of the Expert Discussion ‘Liberalizing Import of Services from Belarus to the EU: A Revolutionary Win-Win Step.’” Official website of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya. Accessed November 27, 2021. https://tsikhanouskaya.org/en/events/news/b1de8d6320627b7.html.

“EU Economic Plan for Democratic Belarus.” Official website of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, July 16, 2021. https://tsikhanouskaya.org/en/economic_support/ad294a8b09bba96.html.

“European Parliament Awards Sakharov Prize to Belarus Opposition.” Voice of America, December 16, 2020. https://www.voanews.com/a/europe_european-parliament-awards-sakharov-prize-belarus-opposition/6199637.html.

“European Union Agrees to End Nearly All Sanctions on Belarus.” Deutsche Welle, February 15, 2016. https://www.dw.com/en/european-union-agrees-to-end-nearly-all-sanctions-on-belarus/a-19050183.

“European Union Steps Up Funding to Belarus Groups.” Euractiv, December 13, 2021. https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/news/european-union-steps-up-funding-to-belarus-groups/.

“Flag of Belarus (1918, 1991–1995).” Wikimedia Commons. Accessed November 23, 2021. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Belarus_(1918,_1991%E2%80%931995).svg.

“Lukashenko Lampooned on Social Media for 3% Approval Rating.” bne IntelliNews, June 15, 2020. https://www.intellinews.com/lukashenko-lampooned-on-social-media-for-3-approval-rating-185414/.

“Protesters Are Western Puppets, Says Lukashenko.” The Hindu, August 20, 2020. https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/protesters-are-western-puppets-says-lukashenko/article32406907.ece.

“State Symbols.” Belarus.by (Republic of Belarus). Accessed November 23, 2021. https://www.belarus.by/en/government/symbols-and-anthem-of-the-republic-of-belarus.

“Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya: EU Sanctions against Belarus Not Enough.” Euronews, December 16, 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/12/16/sviatlana-tsikhanouskaya-eu-sanctions-against-belarus-not-enough-says-opposition-leader.

Adamson, Walter L. Hegemony and Revolution: A Study of Antonio Gramsci's Political and Cultural Theory. London/UK: University of California Press, 1980.

Beissinger, Mark. Nationalist Mobilization and the Collapse of the Soviet State. Cambridge/UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002.

Braguinsky, Serguey. “Postcommunist Oligarchs in Russia: Quantitative Analysis.” The Journal of Law and Economics 52, no. 2 (2009): 307–49. https://doi.org/10.1086/589656.

Cammett, John McKay. Antonio Gramsci and the Origins of Italian Communism. California/US : Stanford University Press, 1967.

Carr, Erward H. The Bolshevik Revolution. 1. Vol. 1. New York/US: W. W. Norton Company, 1985.

Delfi. “Foreign Ministry Accredits Tsikhanouskaya's Team as Belarusian Democratic Representation.” DELFI, July 16, 2021. https://www.delfi.lt/en/politics/foreign-ministry-accredits-tsikhanouskayas-team-as-belarusian-democratic-representation.d?id=87632983.

Dynko, Alyaksandra, and Claire Bigg. “Shocking! Belarusian President Speaks Belarusian.” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, July 2, 2014. https://www.rferl.org/a/shocking-belarusian-president-speaks-belarusian-lukashenka/25443432.html.

Eke, Steven M., and Taras Kuzio. “Sultanism in Eastern Europe: The Socio-Political Roots of Authoritarian Populism in Belarus.” Europe-Asia Studies 52, no. 3 (2000): 523–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/713663061.

Filtenborg, Emil, and Stefan Weichert. “'He Stopped Listening... and Became Cruel': Lukashenko Remembered by Former Campaign Manager.” Euronews, September 28, 2020. https://www.euronews.com/2020/09/24/he-stopped-listening-and-became-cruel-lukashenko-remembered-by-former-campaign-manager.

Forbrig, Joerg, Robin Shepherd, Balasz Jarábik , and David Marples . “International Democracy Assistance to Belarus: An Effective Tool? .” Essay. In Prospects for Democracy in Belarus, 2. ed. Washington/US: German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2009.

Gramsci, Antonio, Quintin Hoare, and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith. Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci. New York, US: International Publishers, 1971.

Hobsbawm, Eric J. Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality. 2nd ed. Cambridge/UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Hrydzin, Uladz. “Belarusians Protest against Lukashenka's Run for Sixth Term as President.” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, May 25, 2020. https://www.rferl.org/a/belarus-protests-politcs/30632716.html.

Ioffe, Grigory. “Understanding Belarus: Economy and Political Landscape.” Europe-Asia Studies 56, no. 1 (2004): 85–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966813032000161455.

Kłysiński, Kamil, and Jeronim Perovic . “Double Reality: The Russian Information Campaign Towards Belarus.” Edited by Stephen Aris, Mathias Neumann, and Robert Orttung. Russian Analytical Digest 206 (September 17, 2017).

Letain, Margot. “The 'Denim Revolution': A Glass Half Full.” OpenDemocracy, April 10, 2006. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/denim_3441jsp/.

Manaev, Oleg, Natalie Manayeva, and Dzmitry Yuran. “More State Than Nation: Lukashenko's Belarus.” Journal of International Affairs 65, no. 1 (2011): 93–113.

Marples, David R. Belarus: From Soviet Rule to Nuclear Catastrophe. New York /US: St. Martin's Press, 1996.

Marx, Karl. “The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte.” Translated by Saul Padover. Marxist Internet Archive. Accessed November 28, 2021. https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/18th-Brumaire.pdf.

Michaluk, Dorota, and Per Anders Rudling. “From the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to the Belarusian Democratic Republic: The Idea of Belarusian Statehood During the German Occupation of Belarusian Lands, 1915-1919.” The Journal of Belarusian Studies 7, no. 2 (2014): 3–36. https://doi.org/10.30965/20526512-00702002.

Mite, Valentinas. “Opposition Politicians Embrace Internet.” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, April 8, 2008. https://www.rferl.org/a/1065515.html.

Mojeiko , Vadim. “Soft Belarusization: A New Shift in Lukashenka's Domestic Policy?” BelarusDigest. Accessed November 28, 2021. https://belarusdigest.com/story/soft-belarusization-a-new-shift-in-lukashenkas-domestic-policy/.

Mozheĭko, Vadnim. “Мягкая Белорусизация. Как Минск Стремится Обособиться От Москвы.” Republic.ru, April 16, 2018. https://republic.ru/posts/90298.

Nechyparenka, Yauheniya. “III. Case-Study Analysis: Belarus.” Democratic Transition in Belarus: Cause(s) of Failure, January 1, 2011, 12–31.

Nohlen, Dieter, and Stöver Philip. Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook. Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2010.

Plokhy, Serhii. The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

Posokhin, Ivan. “Soft Belarusization: (Re)Building of Identity or ‘Border Reinforcement.’” Colloquia Humanistica, no. 8 (2019): 57–78. https://doi.org/10.11649/ch.2019.005.

Reuveny, Rafael, and Aseem Prakash. “The Afghanistan War and the Breakdown of the Soviet Union.” Review of International Studies 25, no. 4 (1999): 693–708. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0260210599006932.

Sannikov, Andrei. “The Accidental Dictatorship of Alexander Lukashenko.” SAIS Review of International Affairs 25, no. 1 (2005): 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2005.0017.

Smok, Vadzim. “Belarus Has an Identity Crisis.” OpenDemocracy, May 14, 2015. https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/belarus-has-identity-crisis/.

Specter, Michael. “Belarus Voters Back Populist in Protest at the Quality of Life.” The New York Times, June 25, 1994. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/06/25/world/belarus-voters-back-populist-in-protest-at-the-quality-of-life.html.

Szporluk, Roman, and Jan Zaprudnik. “Development of Belarusian National Identity and Its Influence on Belarus's Foreign Policy Orientation .” Essay. In National Identity and Ethnicity in Russia and the New States of Eurasia. New York, US: Sharpe, 1994.

Zaprudnik, Jan. “Belarusian Identity and Foreign Policy .” Essay. In National Identity and Ethnicity in Russia and the New States of Eurasia, edited by Roman Szporluk. Armonk, NY: Sharpe, 1994.

Zaprudnik, Jan. Belarus at a Crossroads in History. Boulder/US: Westview Press, 1993.

Žižek , Slavoj. “The Spiritual Wickedness in the Heavens.” Introduction. In Living in the End Times. New York/US: Verso Books, 2011.

[1] Jan Zaprudnik, Belarus at a Crossroads in History (Boulder/US: Westview Press, 1993), 2.

[2] Ibid, 7.

[3] Serhii Plokhy, The Origins of the Slavic Nations: Premodern Identities in Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus (Cambridge/UK: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 2.

[4] Ibid, 50.

[5] Ibid, 55.

[6] Roman Szporluk and Jan Zaprudnik, “Development of Belarusian National Identity and Its Influence on Belarus's Foreign Policy Orientation,” in National Identity and Ethnicity in Russia and the New States of Eurasia (New York/US: Sharpe, 1994), 132.

[7] Dorota Michaluk and Per Anders Rudling, “From the Grand Duchy of Lithuania to the Belarusian Democratic Republic: The Idea of Belarusian Statehood During the German Occupation of Belarusian Lands, 1915-1919,” The Journal of Belarusian Studies 7, no. 2 (November 2014): pp. 3-36, https://doi.org/10.30965/20526512-00702002, 15-17.

[8] Erward H. Carr, The Bolshevik Revolution, vol. 1 (New York/US: W. W. Norton Company, 1985), 397.

[9] Grigory Ioffe, “Understanding Belarus: Economy and Political Landscape,” Europe-Asia Studies 56, no. 1 (2004): pp. 85-118, https://doi.org/10.1080/0966813032000161455, 86.

[10] Ibid, 87.

[11] Rafael Reuveny and Aseem Prakash, “The Afghanistan War and the Breakdown of the Soviet Union,” Review of International Studies 25, no. 4 (1999): pp. 693-708, https://doi.org/10.1017/s0260210599006932, 695.

[12] Ioffe, “Understanding Belarus”, 89.

[13] Serguey Braguinsky, “Postcommunist Oligarchs in Russia: Quantitative Analysis,” The Journal of Law and Economics 52, no. 2 (2009): pp. 307-349, https://doi.org/10.1086/589656, 320-22.

[14] See; Gazprom Transgaz Belarus, accessed November 20, 2021, https://belarus-tr.gazprom.ru/

[15] Emil Filtenborg and Stefan Weichert, “'He Stopped Listening... and Became Cruel': Lukashenko Remembered by Former Campaign Manager,” Euronews, September 28, 2020, https://www.euronews.com/2020/09/24/he-stopped-listening-and-became-cruel-lukashenko-remembered-by-former-campaign-manager.

[16] Michael Specter, “Belarus Voters Back Populist in Protest at the Quality of Life,” The New York Times, June 25, 1994, https://www.nytimes.com/1994/06/25/world/belarus-voters-back-populist-in-protest-at-the-quality-of-life.html.

[17] Zaprudnik, “Belarusian Identity”, 131.

[18] Dieter Nohlen and Stöver Philip, Elections in Europe: A Data Handbook (Baden-Baden: Nomos, 2010), 255-56.

[19] Oleg Manaev, Natalie Manayeva, and Dzmitry Yuran, “More State Than Nation: Lukashenko's Belarus,” Journal of International Affairs 65, no. 1 (2011): pp. 93-113, 89.

[20] Andrei Sannikov, “The Accidental Dictatorship of Alexander Lukashenko,” SAIS Review of International Affairs 25, no. 1 (2005): pp. 75-88, https://doi.org/10.1353/sais.2005.0017, 77-78.

[21] Ibid, 94-95.

[22] Belarusian Popular Front, in Belarusian Беларускі Народны Фронт, was a political movement led by politicians, authors, artists and journalists in the late 1980s and early 1990s that produced a nationalist program, including sovereignty and language reforms. However, in contrast to other post-Soviet nationalist movements, its influence was limited to a few elites’ thoughts. See, Mark Beissinger, Nationalist Mobilization, and the Collapse of the Soviet State (Cambridge/UK: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2002), 254-55.

[23] Yauheniya Nechyparenka, “III. Case-Study Analysis: Belarus,” Democratic Transition in Belarus: Cause(s) of Failure, January 1, 2011, pp. 12-31, 23.

[24] Steven M. Eke and Taras Kuzio, “Sultanism in Eastern Europe: The Socio-Political Roots of Authoritarian Populism in Belarus,” Europe-Asia Studies 52, no. 3 (2000): pp. 523-547, https://doi.org/10.1080/713663061, 523.

[25] Yauheniya, “Case Study”, 24.

[26] “Coat of Arms of Belarus (1991–1995),” Wikimedia Commons, accessed November 23, 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Coat_of_Arms_of_Belarus_(1991).svg?uselang=ru.

[27] “State Symbols,” Belarus.by (the Republic of Belarus), accessed November 23, 2021, https://www.belarus.by/en/government/symbols-and-anthem-of-the-republic-of-belarus.

[28] “Flag of Belarus (1918, 1991–1995) ,” Wikimedia Commons, accessed November 23, 2021, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Flag_of_Belarus_(1918,_1991%E2%80%931995).svg.

[29] Belarus.by, “State Symbols.”

[30] Eric J. Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism since 1780: Programme, Myth, Reality, 2nd ed. (Cambridge/UK: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 54-55.

[31] Marples, Nationalist Mobilization, 253.

[32] David R. Marples, Belarus: From Soviet Rule to Nuclear Catastrophe (New York/US: St. Martin's Press, 1996), 117-18.

[33] See, for instance, U.S. Department of State’s report on Minsk Spring protests in 1996; “1996 Human Rights Report: Belarus”, U.S. Department of State, January 30, 1997, https://1997-2001.state.gov/global/human_rights/1996_hrp_report/belarus.html.

[34] See; “Belarus Government Accused of Human Rights Abuses”, BBC News, November 11, 1997, http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/europe/29562.stm.

[35] This name was surely a reference to the other colour revolutions that occurred in other post-Soviet republics; however, the Jeans Revolution’s influence was both limited and immaterial. Nevertheless, in inventing a different symbol such as “denim”, the opposition appeared to find an embedded, or a consent-generating space of politics. See, Margot Letain, “The 'Denim Revolution': A Glass Half Full,” OpenDemocracy, April 10, 2006, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/denim_3441jsp/.

[36] The term ‘cockroach’ was chosen to refer to a children poem written by Korney Chukovsky. See, Vitali Shkliarov, “Belarus Is Having an Anti-'Cockroach' Revolution,” Foreign Policy, June 4, 2020, https://foreignpolicy.com/2020/06/04/belarus-protest-vote-lukashenko-stop-cockroach/.

[37] Uladz Hrydzin, “Belarusians Protest against Lukashenka's Run for Sixth Term as President,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, May 25, 2020, https://www.rferl.org/a/belarus-protests-politcs/30632716.html.

[38] “Foreign Ministry Accredits Tsikhanouskaya's Team as Belarusian Democratic Representation,” Delfi.en, July 16, 2021, https://www.delfi.lt/en/politics/foreign-ministry-accredits-tsikhanouskayas-team-as-belarusian-democratic-representation.d?id=87632983.

[39] Karl Marx , “The 18th Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte,” trans. Saul Padover , Marxist Internet Archive , accessed November 28, 2021, https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/download/pdf/18th-Brumaire.pdf, 62.

[40] “European Parliament Awards Sakharov Prize to Belarus Opposition,” Voice of America, December 16, 2020, https://www.voanews.com/a/europe_european-parliament-awards-sakharov-prize-belarus-opposition/6199637.html.

[41] “Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya: EU Sanctions against Belarus Not Enough,” Euronews, December 16, 2020, https://www.euronews.com/2020/12/16/sviatlana-tsikhanouskaya-eu-sanctions-against-belarus-not-enough-says-opposition-leader.

[42] “EU Economic Plan for Democratic Belarus,” Official website of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, July 16, 2021, https://tsikhanouskaya.org/en/economic_support/ad294a8b09bba96.html.

[43] The Research Center of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya's Office, for instance, has arranged dozens of seminars in which scholars from different European countries have participated to discuss and reconcile interests of Belarusian opposition class and that of the EU. See, “Conclusions of the Expert Discussion ‘Liberalizing Import of Services from Belarus to the EU: A Revolutionary Win-Win Step,’” Official website of Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, accessed November 27, 2021, https://tsikhanouskaya.org/en/events/news/b1de8d6320627b7.html.

[44] Antonio Gramsci, Quintin Hoare, and Geoffrey Nowell-Smith, Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (New York/US: International Publishers, 1971), 10.

[45] Walter L. Adamson, Hegemony and Revolution: A Study of Antonio Gramsci's Political and Cultural Theory (London/UK: University of California Press, 1980), 10-11.

[46] Li Yan, and Enfu Cheng. “Market Socialism in Belarus: An Alternative to China’s Socialist Market Economy.” World Review of Political Economy 11, no. 4 (2020): 432–43. https://doi.org/10.13169/worlrevipoliecon.11.4.0428.

[47] Li and Cheng, “Market Socialism”, 443.

[48] Yauheniya, “Case Study,” 19.

[49] Joerg Forbrig et al., “International Democracy Assistance to Belarus: An Effective Tool?,” in Prospects for Democracy in Belarus, 2. ed. (Washington/US: German Marshall Fund of the United States, 2009), 87.

[50] “European Union Steps Up Funding to Belarus Groups,” Euractive, December 13, 2021, https://www.euractiv.com/section/europe-s-east/news/european-union-steps-up-funding-to-belarus-groups/.

[51] By 2020, 86% of the Belarusian population have access to the internet. This percentage is much higher than some globally more-integrated countries, such as Turkey. See, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/IT.NET.USER.ZS?locations=BY&view=map&year=2020.

[52] Valentinas Mite, “Opposition Politicians Embrace Internet,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, April 8, 2008, https://www.rferl.org/a/1065515.html.

[53] Vadzim Smok, “Belarus Has an Identity Crisis,” OpenDemocracy, May 14, 2015, https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/odr/belarus-has-identity-crisis/.

[54] In return, except for the arms embargo, whole-scale sanctions on Belarusian authorities including Lukashenko had been lifted by the mid-2016 by the EU. See; “European Union Agrees to End Nearly All Sanctions on Belarus,” Deutsche Welle, February 15, 2016, https://www.dw.com/en/european-union-agrees-to-end-nearly-all-sanctions-on-belarus/a-19050183.

[55] Vadnim Mozheĭko, “Мягкая Белорусизация. Как Минск Стремится Обособиться От Москвы,” Republic.ru, April 16, 2018, https://republic.ru/posts/90298.

[56] Kamil Kłysiński and Jeronim Perovic, “Double Reality: The Russian Information Campaign Towards Belarus,” ed. Stephen Aris, Mathias Neumann, and Robert Orttung, Russian Analytical Digest 206 (September 17, 2017), 5-6.

[57] Vadim Mojeiko, “Soft Belarusization: A New Shift in Lukashenka's Domestic Policy?,” BelarusDigest, accessed Decem, 2021, https://belarusdigest.com/story/soft-belarusization-a-new-shift-in-lukashenkas-domestic-policy/.

[58] Ivan Posokhin, “Soft Belarusization: (Re)Building of Identity or ‘Border Reinforcement,’” Colloquia Humanistica, no. 8 (2019): pp. 57-78, https://doi.org/10.11649/ch.2019.005, 66.

[59] Alyaksandra Dynko and Claire Bigg, “Shocking! Belarusian President Speaks Belarusian,” RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty, July 2, 2014, https://www.rferl.org/a/shocking-belarusian-president-speaks-belarusian-lukashenka/25443432.html.

[60] “Protesters Are Western Puppets, Says Lukashenko,” The Hindu, August 20, 2020, https://www.thehindu.com/news/international/protesters-are-western-puppets-says-lukashenko/article32406907.ece.

[61] Slavoj Žižek, “The Spiritual Wickedness in the Heavens,” Introduction. In Living in the End Times (New York/US: Verso Books, 2011), vii.

[62] Marples, Nationalist Mobilization, 254.

[63] “Lukashenko Lampooned on Social Media for 3% Approval Rating,” bne IntelliNews, June 15, 2020, https://www.intellinews.com/lukashenko-lampooned-on-social-media-for-3-approval-rating-185414/.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

AVİM’de tüm yıl boyunca Uygulamalı Eğitim Programı (UEP) devam etmektedir. Avrasya bölgesine dair çalışmalara ilgi duyan adaylar, bu programa kısa veya uzun dönemli katılımlar için başvuruda bulunabilirler.

Bu sayfada AVİM Uygulamalı Eğitim Programı katılımcılarının hazırlamış oldukları raporlardan bazı örnekler yayınlanmaktadır. Yayınlanan raporlar yalnızca yazarlarının görüşlerini temsil etmektedir ve bu raporların AVİM için bağlayıcılığı bulunmamaktadır.

The Traineeship Program at AVİM is offered throughout the year. Applicants are expected to possess a high interest in Eurasian affairs. Applications for the program may be made either for the short or the long term.

Some examples of the reports prepared by Traineeship Program participants are published on this page. These reports solely reflect the views of their authors and are not binding for AVİM.