HISTORIANS WITHOUT BORDERS

THE USE AND ABUSE OF HISTORY IN CONFLICTS

19-20 MAY 2016

HELSINKI, FINLAND

SEARCHING FOR THE RIGHT APPROACH TO SOLVE THE TURKISH-ARMENIAN CONTROVERSY

Turgut Kerem Tuncel

History often plays a central role in present-day conflicts. Many present-day conflicts have their roots in history. In such cases, what occurred in the past functions as the cause, trigger or catalyzer of current controversies. Most historians agree that the disregard to Germany’s self-determination after World War I as a punishment had been an important factor for the eruption of the next disaster, namely, World War II. History may also be used as an ideological instrument by the parties of present-day rivalries. In such cases, history serves as a justification of present-day ambitions. It has not been long since Serbians relied on history, particularly by presenting Croatians as ustasha, Bosnian Muslims as mujahidin, and themselves as the ‘protector of the Christian Europe from the Ottoman Islamization’ to legitimize their actions while perpetrating an ethnic cleansing in the Balkans. Real or perceived wrong-doings in the past are frequently instrumentalized by the ‘victim’ to achieve certain objectives vis-à-vis the ‘victimizer’ or the third-parties. History has witnessed so many cases in which the ‘victim’ of the past eventually turns into the ‘victimizer’ of the present. Most often than not, after a certain threshold, it becomes impossible to distinguish the victim from the victimizer; who can really tell who the victim and who the victimizer is in Genesis 34? In certain cases, barbarity reaches to such a level that this distinction becomes irrelevant.

The Turkish-Armenian controversy is one of the prime examples of a contemporary conflict in which the past plays a major role both as an objective ground and an ideological tool. The general framework of the historical controversy between Turks and Armenians, and between Turkey and Armenia plus the Armenian diaspora is widely known. However, we are still yet to reach a comprehensive understanding of the complicated history of these two nations, notwithstanding the enormous literature, which is, however, mostly composed of repetitive and mickey mouse publications that are devoid of academic character. Even in 2014, a book could still be published on the ‘Armenian genocide’, which states that those Armenians in Istanbul who were arrested on 24 April 1915 were transported in ships to military prisons near Ankara.[1] I this book, however, the author does not explain “how this was possible when Ankara is hundreds of kilometers from the nearest coast.”[2] Books and articles based on ‘documents’, the falsehood of which has long been proved can still be published. We see studies that distort authentic documents, as well.[3]

The purpose of this paper is not to discuss the complicated Turkish-Armenian history or review the relevant literature to unveil its incompetency that is in serious need of improvement. Instead, the aim here is to draw attention to certain mistakes that contribute to the perpetuation of the dispute in order to find the appropriate, effective, and constructive approach that can help the normalization between Turkey and Armenia, and, as the next step, reconciliation between Turks and Armenians.

What is the controversy all about?

Although much of the debate revolves around different interpretations of the common history of Turks and Armenians with a burgeoning literature, in reality, the historical controversy between Turks and Armenians has got stuck in just one word: genocide. Armenians resolutely reject any characterization of the terrible events of 1915 besides genocide. On the other hand, Turks, admitting the great tragedy of 1915, categorically refuse this characterization. In fact, it can be said that the controversy between Turks and Armenians is much narrower and maybe even something other than a historical debate. It is rather a ‘war’ fought for and against a single word.

Significantly, most of the literature is composed of studies that aim to prove the truth or untruth of ‘genocide’ rather than to unveil the details of the events and the causal relationships among them. This partisan and retrospective approach, however, diminishes the quality and reliability of this literature, and often makes it difficult to distinguish scholarly analyses from political manifestos, and arguments from slogans. Scholars and public figures acting as partisans do not hesitate to blame the ‘other’ as paid agents of the ‘antagonist’. In such an environment, it becomes less bizarre than it should be to see scholars shouting slogans in public rallies.[4] Unfortunately but understandably, this context alienates independent and free-minded researchers from the subject.

Having said that, it would be naïve to believe that the controversy is simply about determining whether 1915 events were genocide or not per se. The struggle for the recognition of the ‘genocide’ has, in time, become an instrument for the constitution of the contemporary Armenian identity and the unity amongst Armenians around the globe. Because Armenians have turned their belief in the ‘genocide’ into the central pillar of their identity, invalidation of the genocide claim would lead to a crisis in the Armenian world. Besides this, ‘genocide’ is a leverage used by Armenians and some third parties to achieve certain objectives. This can be seen by recalling the arguments about the alleged imperative of opening of the land border between Turkey and Armenia, which is almost always associated with genocide claims, or EU progress reports on Turkey that simultaneously bring forward the matters of recognition of the 1915 events as genocide and the opening of the Turkey-Armenia land border.[5] Reviewing the Armenian traditional and social media contents produced during the clashes between Armenian and Azerbaijani forces on 1-5 April 2016 helps one to realize that genocide allegations are even instrumentalized to claim some of the territories within the internationally recognized borders of Azerbaijan.

Two Wrong Approaches

At the heart of the disagreement on the nature of the events of 1915 lies a fundamental, yet less-known, technicality. Those who support the genocide claim, including non-legal scholars such as historians, sociologists, and political scientists, regard any mass atrocity that results in huge number of losses and heavy sufferings as genocide. Importantly, they tend to characterize the events by looking at their consequences. On the other hand, those who reject genocide claims including legal scholars, highlight the fact that genocide is a legal term. They rely on the legal definition of the crime of genocide and draw attention to the distinction between the two components of a crime, namely, the actus reus (the objective element of a crime) and the mens rea (the guilty mind; a guilty or wrongful purpose; a criminal intent; guilty willfulness). They insist that irrespective of the consequences, the mens rea element of the crime of genocide is missing in the events of 1915, therefore, in legal terms, this tragedy cannot be characterized as genocide. Put differently, they argue that genocide is not a historical, sociological, or philosophical term, but a legal term and a crime, and unless the mens rea element of the alleged crimes in 1915 is proved beyond doubt, it is not possible to characterize the 1915 events as genocide.

Secondly, it can be seen that those who struggle for the recognition of the 1915 events as genocide do so in wrong venues. To understand this, one needs a clear grasp of the strategy employed by the advocates of the genocide hypothesis. Since 1987 or 1999, when Turkey applied for membership to the European Economic Community and Turkey was approved as a EU member candidate, respectively, for this group, the main method of winning the dispute on the characterization of the 1915 events have been pushing international organizations, supra-national bodies and the parliaments of third countries to issue resolutions and statements on the ‘Armenian genocide’. Lobby organizations and the Armenian governments concentrated much of their effort to ensure the passage of such resolutions and statements by third parties.

This approach is wrong, first of all, and probably first and foremost, because history is a science that should be studied and debated over and over again by historians, not something to be decided by politicians. Science, hence history, shall be free from political statements and should beyond political objectives. Loads of words can be said on this point, yet this is not the purpose of this paper. For some mind opening debates on this issue, one may refer to, for example, the website of the association Liberté pour l’Histoire.[6] Here, it suffices to say that what we witness is a much broader and serious problem than different interpretations of 1915 events. What is at stake is a threat against historical scholarship. Secondly as mentioned above, in fact, the core of the controversy is not about history per se, but the legal characterization of a historical event. Therefore, the ultimate venue for determining the nature of the 1915 events, and hence the solution of the controversy, is not halls that host history conferences, not to mention parliaments, but courtrooms of the authorized tribunals defined by Article 6 of the 1948 Genocide Convention.[7]

To summarize, first we see a problem in determining the right way to establish an event as genocide. Whereas one group looks at the consequences, the other group, underlining that genocide is a legal term and crime instead of a historical, sociological or philosophical term, puts emphasis to the intent of the actors, i.e., the mens rea element. Secondly, those who insist that the 1915 events were genocide try to impose this view through resolutions and statements of political bodies and actors. This is a threat against the science of history. Moreover, ultimately, neither historians nor politicians, but only judges can make a decision regarding a legal issue. The following three examples shall help to elaborate these points in order to arrive at the correct approach. Certainly, many more examples can be utilized, yet for this paper following three examples will be sufficient.

The Three Examples

1987 and 2015 European Parliament Resolutions and the Judgment of the Court of Justice of the European Union in 2003

On 15 April 2015, the European Parliament adopted a resolution titled “European Parliament Resolution on the Armenian Genocide 100th Anniversary”[8] with 351 to 269 votes and 22 absentees. The Parliament declared that it recognized “the tragic events that took place in 1915-1917 against the Armenians in the territory of the Ottoman Empire” as “genocide as defined in the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of 1948” with words of certainty by relying on the “increasing number of [EU] Member States and national parliaments” that recognize the ‘Armenian genocide’. The Resolution also “invite[d] Armenia and Turkey take steps for reconciliation” including opening of the Turkey-Armenia border.[9] Article 2 of this resolution referred to another European Parliament resolution that was issued in 1987 with the title “Resolution on a Political Solution to the Armenian Question”[10] which labeled 1915 events as genocide some twenty-eight years ago.[11]

In fact, the aftermath of the 1987 resolution needs to be remembered in order to archive an understanding of the nature of this and similar resolutions. After Turkey was given the status of candidate state for the European Union membership in December 1999, Euro-Arménie ASBL based in Marseille and two French-Armenians applied to the Court of First Instance of the European Communities (which became the General Court as a constituent court of the Court of Justice of the European Union after 2009)[12] for “compensation for the harm caused to them by, inter alia, recognition of Turkey's status as a candidate for accession to the European Union, although that State has refused to acknowledge the genocide perpetrated in 1915 against the Armenians living in Turkey”.[13] The applicants argued that the European Parliament Resolution of 18 June 1987 was “on a political solution to the Armenian question binding legal force in respect of the European Community”.[14] The applicants insisted that 18 June 1987 Resolution made Turkey’s accession to the European Union conditional on the recognition of the 1915 events as genocide. The complaint was that the European Council did not honor that resolution. Applicants claimed that “as members of the Armenian community and descendants of survivors of the genocide in question, they have suffered non-material damage.”[15] They argued that the conduct of the European Council affronted their dignity.[16]

The Court judged that there was no causal relationship between European Council’s acceptance of Turkey’s candidacy to the EU membership and the allegedly harmed dignity of the Armenians. The Court, accordingly, defied the related claims.[17]

Yet, what was important as regards to the 1987 European Parliament Resolution, hence for similar resolutions and statements, was that the Court stated the following:[18]

It suffices to point out that the 1987 Resolution is a document containing declarations of a purely political nature, which may be amended by the Parliament at any time. It cannot therefore have binding legal consequences for its author nor, a fortiori, for the other defendant institutions.

As such, the Court not only determined the political nature of this and similar resolutions, but also disclosed that they could be altered at any time.

France

On 29 January 2001, the French Parliament passed a one-article law that states “France officially recognizes the 1915 Armenian genocide.” In 2012, before the April-May 2012 presidential election, a law that criminalized the denial of the genocides recognized by law was passed. The next month, the French Constitutional Council declared that this law was against the freedom of expression and the separation of powers. On this ground, the French Constitutional Council invalidated this law.[19]

In October 2015, French citizen Vincent Reynouard, who was convicted for denying the Holocaust, applied to the French Constitutional Council against the Gayssot Act that criminalizes the denial of crimes against humanity defined in the Charter of the International Military Tribunal of 1945, on the basis of which Nazis were tried and convicted by the International Military Tribunal at Nuremberg. Reynouard claimed that the Gayssot Act was a violation of freedoms of expression and opinion. He also argued that the Gayssot Act violated the principle of equality before the law by stressing that denial of crimes against humanity other than those indicated in the Gayssot Act was not punishable. In order to substantiate his argument, Reynouard insisted that whereas “denial of the Armenian genocide” was not a breach of freedom of expression, denial of the Holocaust was so. On these bases, Reynouard demanded that Holocaust denial should be de-criminalized. The French-Armenian associations intervened and asked for the criminalization of the ‘denial of the Armenian genocide’, just like the Holocaust.

In January 2016, the French Constitutional Council declared its judgment. The Council stated that disputing the existence of crimes committed during World War II that were established by French or international courts was in itself an incitement to racism and antisemitism. As to the question of equality, the French Constitutional Council drew a distinction between the denial of crimes against humanity established by a French court or authorized international court and those that have not been established by either of these two.[20]

By this way, the French Constitutional Council made a categorical distinction between the Holocaust and the events of 1915. The Council stated that whereas Holocaust is a crime against humanity established by an authorized court and its denial is an incitement to racism, none of these two is true with respect to the 1915 events.

Sweden

On 12 June 2008, the Swedish parliament voted a resolution for the recognition of the 1915 events as genocide. The resolution was rejected with a vote 245 to 37 (1 abstain, 66 absent),

Four reasons were underlined for the rejection of this resolution. They were as follows:

1) “no particular consideration regarding the Armenian situation has ever been in form of an UN Resolution, either in 1985 or any other occasion.”

2) “the Committee understands that what engulfed the Armenians, Assyrian/Syrians and Chaldeans during the reign of the Ottoman Empire would, according to the 1948 Convention, probably be regarded as genocide, if it had been in power at the time.”

3) “there is still a disagreement among the experts regarding the different course of events of the dissolution of the Ottoman Empire. The same applies to the underlying causes and how the assaults shall be classified.”

4) “[in regard to the development in Turkey] ‘…in the time being, it would be venturesome to disturb an initiate and delicate national process’ [which could fuel the extremists in the country]” [21]

21 months later, on 11 March 2010, the same Swedish parliament adopted a resolution that recognized the ‘genocide of “Assyrians/Syriacs/Chaldeans and Pontic Greeks of 1914-1923’ with a vote 131 to 130, and 88 abstain or absent.[22]

Some Lessons

The decision of the General Court as a constituent court of the Court of Justice of the European Union in 2003 in the case of the 1987 European Parliament Resolution and the following lawsuit is a key document that clarifies the nature of the European Parliament Resolutions and similar texts. According to the judgment of this court, these resolutions and statements are legally non-binding and inconsequential political declarations that may be amended at any time.

This point should be underlined with further clarification that was mentioned above. Genocide is a narrowly defined and a strictly legal term and a crime defined by law. For this basic reason, this crime can be established only through a legal process. The main international document on the crime of genocide is the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of 1948. It is a binding document for its signatories. Article 2 of the Convention defines the crime of genocide. Article 3 identifies which acts are punishable. Article 6, on the other hand, outlines the procedure of the legal establishment of this crime, as follows:

Persons charged with genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in Article 3 shall be tried by a competent tribunal of the State in the territory of which the act was committed, or by such international penal tribunal as may have jurisdiction with respect to those Contracting Parties which shall have accepted its jurisdiction.[23]

As such, Article 6 explicitly and beyond any question reveals that only a competent tribunal can judge whether an act is crime of genocide; the crime of genocide can be established only by such judgment. Unless there is such a judgment, genocide claims remain as only claims. The ruling of the French Constitutional Council also indirectly highlighted this point.

International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY) established in 1993 and International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda (ICTR) established in 1994 are the two examples of a competent court and its functioning for the trial of crimes such as genocide. Importantly, the ICJ in Application of the Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Bosnia and Herzegovina v. Serbia and Montenegro) explained the standard of proof of the crime of genocide as follows:

The Court has long recognized that claims against a State involving charges of exceptional gravity must be proved by evidence that is fully conclusive. It requires that it be fully convinced that allegations made in the proceedings, that the crime of genocide or the other acts enumerated in Article III have been committed, have been clearly established.

The same standard applies to the proof of attribution for such acts. In respect of the Applicant’s claim that the Respondent has breached its undertakings to prevent genocide and to punish and extradite persons charged with genocide, the Court requires proof at a high level of certainty appropriate to the seriousness of the allegation.

As such, the ICJ set a very high threshold for the determination of the genocidal intent (dolus specialis), in other words, the mens rea component of the crime of genocide, and on that ground refused the genocide claims whether the actus reus component of the crime was present or not. This means that neither resolutions, which “may be amended by the Parliament at any time”, nor popular discourses, ‘public opinion’, or even high quality scholarly studies can decide whether an event is genocide or not. Only an authorized court can do this, and only if the mens rea of the acts are established “beyond doubt”. In fact, this seems to be the reason why so much effort and resource are allocated to PR campaigns to ensure resolutions and statements instead of applying to courts, which is, however, the correct approach for those who insist on the genocide hypothesis.

Uneasy Questions

Turning back to the above mentioned examples, some further interesting points can be detected. Many resolutions underline higher ideals of humanity such as justice, peace, and human rights as European values and associate the recognition of 1915 events as genocide with internalization of these values. Alas, this rhetoric raises some questions.

The rule of law and separation of powers are the main principles of democracy that the EU champions as one of its core values. In this regard, it is striking that legislative and executive bodies in Europe assume the role of the judiciary and issue resolutions on a legal matter. Moreover they overlook the clearly defined process of the establishment of the crime of genocide as set by the 1948 Genocide Convention.

The reference to European values raises other questions, as well. The 2015 European Parliament Resolution was adopted by 351 votes from the total of 642. This is equal to %54.7 of the total votes, which neither means unanimity nor a substantial majority. Recall that the Swedish resolution of 2010 was passed by just one vote.

Besides the question on whether it is legitimate and correct to make decisions on controversial historical events with a small margin and if politicians are licensed to make judgments on the character of such complex set of events, the question remains whether % 45.3 of the MPs in the European Parliament or 130 members of the 261 seated Swedish Parliament are remorseless and unethical ‘deniers’, who have not internalized “European values”. If one or more of these is true, the legitimacy of the entire European Parliament and many of the European country parliaments should be questioned.

One must also find an answer to the following question: if the ‘Armenian genocide’ is such an established fact, how can % 45.3 of the MPs in the European Parliament and almost half of the Swedish MP’s vote against the resolution? Inter alia, as to the argument of ‘established truth’, one has to remember that, the Second Chamber of the European Court of Human Rights in its verdict on Perinçek v. Switzerland case on 17 December 2013 stated that:

It is even doubtful that there could be a ‘general consensus’, in particular a scientific one, on events such as those that are in question here, given that historical research is by definition open to debate and discussion and hardly lends itself to definitive conclusions or objective and absolute truths.[24]

Talking about the “truth”, as to the Swedish Parliament’s differential decisions, one may wonder what changed in the ‘truth of the Armenian genocide’ in two years between 2008 and 2010. Likewise, one may expect accuracy with respect to the timeline of an historical truth, not different dates in different resolutions like we see in the European Parliament and Swedish resolutions.

Lastly, resolutions as a rule underline the need for the Armenian-Turkish reconciliation. As to that, a more pragmatic consideration would be to investigate if these resolutions serve this purpose. Those who are familiar with the social and political spheres in Turkey would answer this question negatively.

What Shall be Done?

Given that parliamentary resolutions and social and political pressures do not help to resolve the controversy between Turks and Armenians, constructive and correct ways to achieve this end shall be investigated. The starting point of this endeavor shall be to frame the controversy in a correct way. The core of the controversy is the politicization of history. Through historical claims, political ends are sought and while doing that history is written and/or interpreted accordingly. Particularly, history is written retrospectively to prove or disprove the existence of genocide. In brief, the historical serves the political.

This must be changed. The first constructive step, therefore, should be to free the historical from the political. This requires independent and high quality historical scholarship. It is apparent that those who even have not taken a look at the map of Anatolia once and yet dare to write a book on the ‘Armenian genocide’, and certain international associations of “genocide scholars” composed of researchers who have built their carriers to prove what they believe to be the truth, cannot contribute to this cause. For that, despite all the practical difficulties ahead, ways should be found to bring historians together to carry out scholarly research on the 1915 events and feed each other with their converging or diverging findings.

Secondly, attention should be paid to the judgments of the French Constitutional Council in 2012 and 2016, as well as the judgment of the European Court of Human Rights on Perinçek v. Switzerland case that was declared on 15 October 2015.[25] As mentioned above, the French Constitutional Council determined that whereas there is an international court decision about the Holocaust, in the case of the 1915 events, such a valid judgment does not exist. By that way, the Council affirmed the unique status of the Holocaust. Like the French Constitutional Council, the ECtHR that handled the Perinçek v. Switzerland case, in its judgment, once again pointed out the right venue for making such a judgment. It should be kept in mind that the 1948 Genocide Convention is the fundamental international document, and ICTY and ICTR are the two examples that set out the legal procedures and arguments. All these make it clear that the legal character of an event can only be determined through a legal process by an authorized court following the legal procedures and methods.

In any case, historical scholarship should not be the servant of any goal. It should be studied by scholars whose aim is to uncover the past events in their causal relationships for scholarly passions, not to prove or disprove a claim for this or that objective. Fortunately, the ECtHR judgment on Perinçek v. Switzerland and the French Constitutional Council’s decision on Vincent Reynouard application are two positive developments that should encourage scholars to work on Turkish-Armenian history, as they invalidate accusations of denialism, racial hatred, anti-Armenianess and so on that are directed to those who bring new arguments forward.

It also important to recall that the ECtHR stated that public and scholarly debates on the 1915 events are “a matter of public interest” and in a democratic country there is no need to subject minority views “to a criminal penalty in order to protect the rights of the Armenian community”. This is an important evaluation, which nullifies the attempts to silence views that fall out of the ordinary. As a correction to this dangerous, reactionist, and despotic approach, the ECtHR defends the freedom of expression of even unpopular views by framing the debate on 1915 as serviceable to the public interest. The ECtHR Grand Chamber’s framing the matter as such might be revealing that Europe has learnt lessons from the dark days of the Middle Ages when freedoms were ignored and suppressed in defense of the ‘sacreds’. Reputable and non-attached scholars must take this as a call to duty to shed light on the complicated Turkish-Armenian history.

[1] See, Geoffrey Robertson Q.C.. An Inconvenient Genocide: Who Now Remembers the Armenians?, London: Biteback Publishing, 2014, p. 48.

[2] Jeremy Salt, A Lawyer’s Blundering Foray into History, Review of Armenian Studies, 2015, No: 31, p. 336.

[3] For some studies that explores such studies, see: Maxime Gauin, “Aram Andonian’s ‘Memoirs of Naim Bey’ and the Contemporary Attempts to Defend their Authenticity’”, Review of Armenian Studies, 2011, No. 23, pp. 233-292; Şinasi Orel and Sürreya Yuca, The Talât Pasha “Telegrams”: Historical fact or Armenian fiction?, Nicosia-Oxford: K. Rüstem & Brothers/Oxford University Press, 1986; Jeremy Salt, “Forging the Past: OUP and the Armenian Question”, Eurasia Critique, January 2010,

http://www.tc-america.org/scholar/forging_the_past_OUP_and_the_Armenian%20question.html.

For the studies that demonstrate how authentic documents are distorted, see: Maxime Gauin, “Review Essay: ‘Proving’ a ‘Crime against Humanity’?”, Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, Vol. 35, No. 1, March 2015, pp. 141-157; Guenter Lewy, The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey, Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005, pp. 46, 82-89, 94 and 160-161; Erman Şahin, “Review Essay: A Scrutiny of Akçam’s Version of History and the Armenian Genocide”, Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, Vol. 28, No. 2, August 2008, pp. 303-319.

[4] See, for example the YouTube video that shows Taner Akçam, a ‘genocide scholar’ and a champion of the cause of the ‘recognition of the Armenian genocide’, giving a speech at a public rally in New York in April 2015 at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KCBEswJ2P8U.

[5] Turkey closed its land border with Armenia not as a reaction to the genocide allegations, but as a protest to the Armenian occupation of Kalbajar region of Azerbaijan in 1993. Note that the Turkey-Armenia border was established by Kars Treaty in 1921. However, Armenian political elite refuse to openly declare that Armenia recognizes this border. For an example, see Mehmet Oğuzhan Tulun, The Art of Dodging the Question, 19.03.2015, http://avim.org.tr/en/Yorum/THE-ART-OF-DODGING-THE-QUESTION (latest access 28.04.2016).

[6] For the website of Liberté pour l’Histoire, visit

http://www.lph-asso.fr/index.php?option=com_content&view=category&layout=blog&id=1&Itemid=5&lang=e. n (latest access 26.04.2016).

[7] Article 6 of the 1948 Genocide Convention states:

Persons charged with genocide or any of the other acts enumerated in article III shall be tried by a competent tribunal of the State in the territory No. I02Z 282 United Nations Treaty Series 1951 of which the act was committed, or by such international penal tribunal as may have jurisdiction with respect to those Contracting Parties which shall have accepted its jurisdiction.

[8] The resolution is available at http://great-nephew4.rssing.com/browser.php?indx=3666141&item=10577 (latest access 28.04.2016).

[9] This is another example of associating the recognition of 1915 events as genocide and opening of the land border between Turkey and Armenia.

[10] The resolution is available at

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/intcoop/euro/pcc/aag/pcc_meeting/resolutions/1987_07_20.pdf (latest access 28.04.2016).

[11] Article 2 of the 1987 Resolution stated the following:

Believes that the tragic events in 1915-1917 involving the Armenians living in the territory of the Ottoman Empire constitute genocide within the meaning of the convention on the prevention and the punishment of the crime of genocide adopted by the UN General Assembly on 9 December 1948; Recognizes, however, that the present Turkey cannot be held responsible for the tragedy experienced by the Armenians of the Ottoman Empire and stresses that neither political nor legal or material claims against present-day Turkey can be derived from the recognition of this historical event as an act of genocide.

Interestingly, articles 10 and 11 of the Resolution expressed concerns of the European Parliament about the Armenian communities in Iran and the USSR.

[12] Before 2009, the Court of First Instance was the European juridical body that was to hear the cases that were opened by individuals and member states against the institutions of the European Union. After 2009, the Court of First Instance was transformed into the General Court as a constituent court of the Court of Justice of the European Union.

[13] For the judgment visit, http://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?docid=48869&doclang=EN (latest access 28.04.2016).

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] Ibid. The applicants stated that:

…the memory of the victims of that genocide and the concern for historical truth are an integral part of the dignity of all Armenians. Moreover, since that genocide is an integral part of the history and identity of the Armenian people, the identity of the applicants is itself irreparably affected by the conduct of the defendant institutions. Finally, calling into question the reality of the [Armenian] genocide brings about marginalisation and a feeling of inferiority within the Armenian community. Thus the attitude of the Republic of Turkey has the effect of ostracising the applicants, since they are regarded as second-rate victims. Those circumstances result in the applicants' harbouring feelings of deep injustice, which also prevents them from completing the mourning process satisfactorily.

[17] Ibid.

Secondly, as regards the requirement that the applicants must have suffered actual and certain damage, the applicants clearly confined themselves in their application to relying in general terms on non-material damage caused to the Armenian community, without giving the least indication as to the nature or extent of the damage which they consider they had suffered individually. Therefore the applicants have supplied no information that would enable the Court to find that the applicants in fact suffered actual and certain damage themselves (see, to that effect, Case T-99/98 Hameico Stuttgart and Others v Council and Commission [2003] ECR II-2195, paragraphs 68 and 69).

[18] Ibid.

[19] For the French Constitutional Council’s judgment in 2012 visit: http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/conseil-constitutionnel/english/case-law/decision/decision-no-2012-647-dc-of-28-february-2012.114637.html

[20] For the French Constitutional Council’s judgment in 2016 visit http://www.conseil-constitutionnel.fr/conseil-constitutionnel/francais/les-decisions/acces-par-date/decisions-depuis-1959/2016/2015-512-qpc/decision-n-2015-512-qpc-du-8-janvier-2016.146840.html (latest access 28.04.2016).

It should be highlighted that the French Constitutional Council highlighted the fundamentally racist dimension of Holocaust denial. Contrary to what most of the people believe the Gayssot act does not deal with Holocaust denial only. It generally reinforces the Pleven Act of 1972 against racism, particularly in adding ineligibility to the list of sentences that can be pronounced in case of incitement to racism or refusal of service/sale for racist reasons. Secondly, the French Constitutional Council stated that verdicts of a foreign national court cannot have the legal value of an international one recognized by France or a decision taken by French justice.

[21] Vahagn Avedian, “Editorial: Sweden: The Champion of Human Rights, Revised”, 12.06.2008, http://www.armenica.org/editorial/ledare080612.html

[22] For the resolution visit: http://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/motion/folkmordet-1915-pa-armenier_GW02U332 (latest access 28.04.2016).

[23] For this convention visit: https://treaties.un.org/doc/Publication/UNTS/Volume%2078/volume-78-I-1021-English.pdf (latest access 28.04.2016).

[24] For the text of this judgment visit http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{"itemid":["001-139724"]} (latest access 28.04.2016). The Grand Chamber judgment did not delve specifically into this issue like the Second Chamber did, yet it made no effort to refute the Second Chamber’s reasoning. This comes to mean that the Grand Chamber judgment simply clarified and reinforced the Second Chamber’s judgment.

[25] The text of this judgment is available at: http://hudoc.echr.coe.int/eng#{"fulltext":["perincek v.switzerland"],"documentcollectionid2":["GRANDCHAMBER"],"itemid":["001-158235"]} (latest access 28.04.2016).

© 2009-2025 Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi (AVİM) Tüm Hakları Saklıdır

Henüz Yorum Yapılmamış.

-

LAVROV’UN ERİVAN’DAKİ AÇIKLAMALARI TÜRKİYE-RUSYA İLİŞKİLERİNİN GELECEĞİNE İŞARET EDİYOR (ÖZEL)

LAVROV’UN ERİVAN’DAKİ AÇIKLAMALARI TÜRKİYE-RUSYA İLİŞKİLERİNİN GELECEĞİNE İŞARET EDİYOR (ÖZEL)

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 18.10.2016 -

REVERSALS OF RESOLUTIONS ON 1915 EVENTS

REVERSALS OF RESOLUTIONS ON 1915 EVENTS

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 28.11.2016 -

SEARCHING FOR THE RIGHT APPROACH TO SOLVE THE TURKISH-ARMENIAN CONTROVERSY

SEARCHING FOR THE RIGHT APPROACH TO SOLVE THE TURKISH-ARMENIAN CONTROVERSY

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 15.02.2017 -

NATO GERÇEK HEDEFİNİ HAZİRANDA AÇIKLAR - ANAYURT GAZETESİ - 30.03.2022

NATO GERÇEK HEDEFİNİ HAZİRANDA AÇIKLAR - ANAYURT GAZETESİ - 30.03.2022

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 31.03.2022 -

WHAT’S NEXT AFTER PUTIN’S FOURTH ELECTORAL VICTORY? - HÜRRIYET DAILY NEWS - 30.03.2018

WHAT’S NEXT AFTER PUTIN’S FOURTH ELECTORAL VICTORY? - HÜRRIYET DAILY NEWS - 30.03.2018

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 30.03.2018

-

STRATEGICALLY MUM: THE SILENCE OF ARMENIANS (PART FIVE) - 08.2021

STRATEGICALLY MUM: THE SILENCE OF ARMENIANS (PART FIVE) - 08.2021

Iver TORIKIAN 03.12.2021 -

STUDENT GROUP AT CAL STATE NORTHRIDGE BOASTS OF ‘SHUTTING DOWN’ SPEECH BY AWARD-WINNING SCHOLAR - WASHINGTON POST - 15.11.2016

STUDENT GROUP AT CAL STATE NORTHRIDGE BOASTS OF ‘SHUTTING DOWN’ SPEECH BY AWARD-WINNING SCHOLAR - WASHINGTON POST - 15.11.2016

Eugene VOLOKH 16.11.2016 -

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH PRIME MINISTER OF TRNC: 'THE FEDERAL SOLUTION' CANNOT GO BEYOND A DREAM - UNITED WORLD - 20.07.2020

EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW WITH PRIME MINISTER OF TRNC: 'THE FEDERAL SOLUTION' CANNOT GO BEYOND A DREAM - UNITED WORLD - 20.07.2020

Mehmet PERİNÇEK 23.07.2020 -

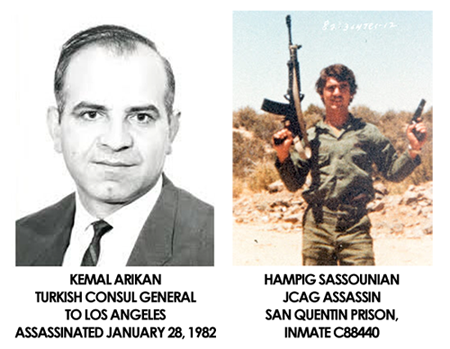

EARLY PAROLE HEARING FOR ARMENIAN TERRORIST IN US DENIED – DAILY SABAH – 01.08.2019

EARLY PAROLE HEARING FOR ARMENIAN TERRORIST IN US DENIED – DAILY SABAH – 01.08.2019

Daily Sabah 01.08.2019 -

AZERBAIJAN TALKS UP ZANGAZUR CORRIDOR AMONGST ARMENIAN CONCERNS AS TRANSIT TRADE GROWS - SILK ROAD BRIEFING - 18.07.2022

AZERBAIJAN TALKS UP ZANGAZUR CORRIDOR AMONGST ARMENIAN CONCERNS AS TRANSIT TRADE GROWS - SILK ROAD BRIEFING - 18.07.2022

Silk Road Briefing 22.07.2022