Dr. Yauheni PREIHERMAN(*)

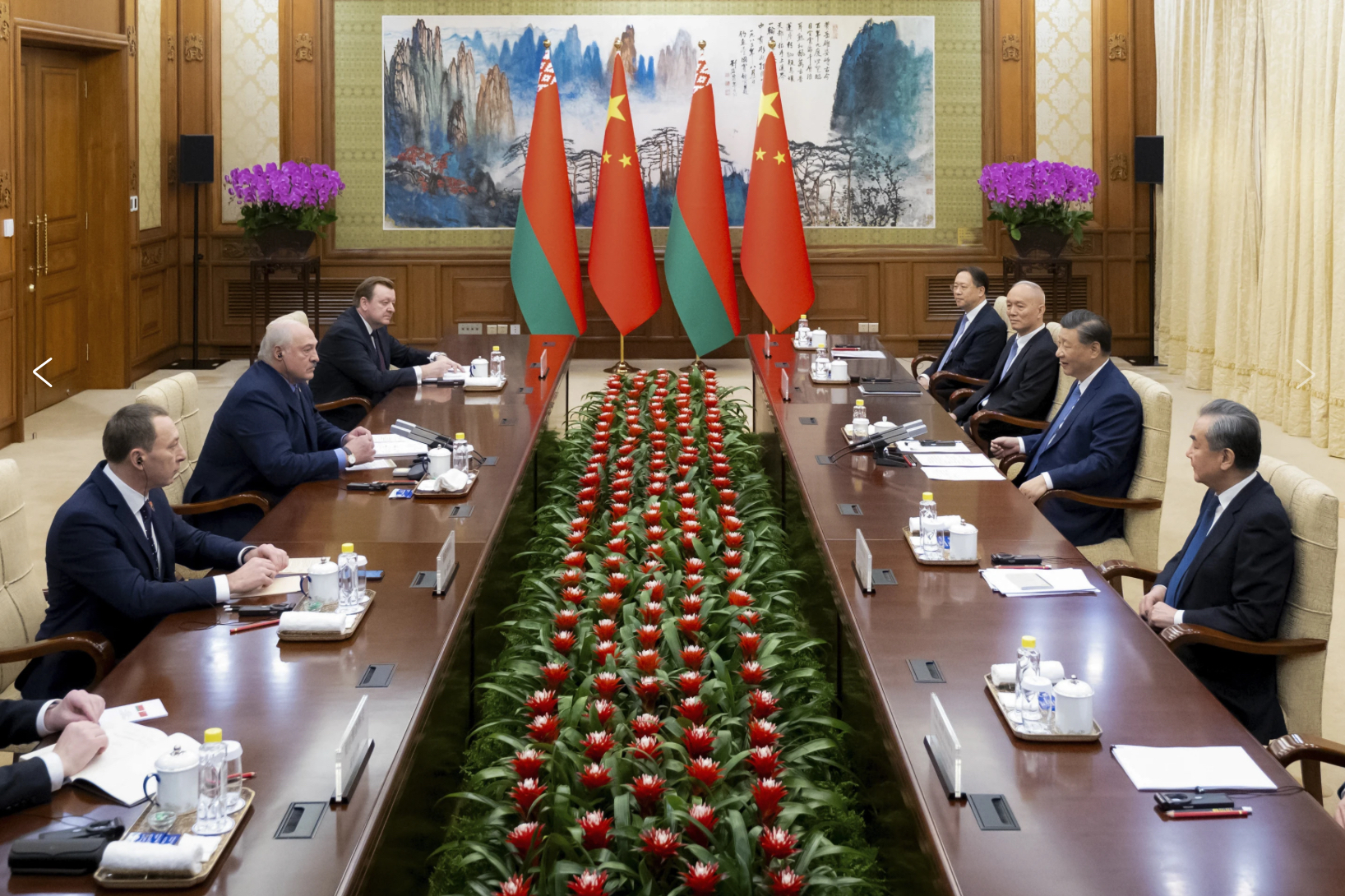

In early December 2023, the President of Belarus, Aleksandr Lukashenko, paid a working visit to China, which looked noteworthy due to at least two factors. Firstly, it had not been announced in advance and, according to the Belarusian leader, was organized “expeditiously.” Secondly, it was already Lukashenko’s second visit to Beijing in 2023; as recently as in March 2023, he paid a state visit bringing along a large government delegation. Such regularity of bilateral visits seems atypical for two disparate states that are approximately 6,000 km apart and, thus, appear not to share a particularly substantive common agenda. Not surprisingly, the very fact of the visit gave birth to numerous speculations.

While the December visit, indeed, came as a surprise to most observers, it should hardly invite sensational interpretations. If anything, the meeting itself and the evolution of Belarus-China relations show that Beijing and Minsk are looking for ways to advance cooperation amid numerous international challenges.

Long-established Relations that Took Off in the 2010s

Belarus and China established diplomatic relations on 20 January 1992. However, until about the 2010s, few noteworthy developments took place in their cooperation. The rise of Beijing’s geostrategic ambitions, and specifically the launch of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, infused new energy into the partnership. For both countries, the rationale looked quite straightforward.

Beijing regarded Belarus’ geographic position as crucial for linking China with the EU along the Eurasian land bridge. Belarus, bordering on the EU and having a well-functioning railway and road network, and border infrastructure, appeared as a natural gateway to the EU. Especially as the fighting in Donbas and the Russian takeover of Crimea started to undermine the stability of Ukraine already in early 2014, which made the latter a less attractive logistical alternative. Belarusian membership of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) and other post-Soviet groupings, such as the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) and the Union State of Belarus and Russia, provided another potential benefit for Chinese investors – that is, tariff-free exports of goods produced in Belarus to post-Soviet markets. Thus, Belarus’ location looked appealing not only as an efficient transit corridor but also as a logistical and production hub with relatively easy access to both the EU and EAEU.

Minsk, on its part, also perceived multiple economic and even national security opportunities in enhancing cooperation. Expanding Chinese export potential, including BRI’s massive designs, corresponded to Belarusian interest in maximizing its own logistical capacities and becoming a crucial element of transcontinental supply chains. Revealingly, in the 2010s, the transport sector – primarily, road and railway transport services – accounted for about 5-6% of the country’s GDP. Belarus’s share in global transport services exports amounted to 0,404% in 2020, whereas its overall share in the global economy stayed at 0,144%. Yet, according to the Belarusian government, cargo transit corridors in the country were used only up to 25-40% of their capacity, which incentivized Minsk to look for ways of further intensifying transport flows.

In addition, Belarus had an interest in accessing Chinese investment, funding, and technology, both bilaterally and within the BRI framework. Moreover, Beijing presented a far-away geopolitical option to slightly diversify country’s key traditional relationships with Russia and the EU. While China could not become a real substitute for those partners (and no one in Minsk was thinking in substitution terms), its cooperation helped Belarus to acquire additional room for international maneuver, which is always vital for smaller states that find themselves in-between competing geopolitical rationalities.

Cooperation Agenda Prior to 2020

In line with the mutually beneficial rationale, Minsk and Beijing began to expand cooperation in various fields. The first noticeable developments took place in late 2009-early 2010, when China’s Eksimbank and State Development Bank allocated $5.7 billion and $8.3 billion, respectively, for investment projects in Belarus. In March 2010, during a visit to Minsk by Xi Jinping, then China’s deputy president, the two countries reached multiple economic agreements and issued a joint communiqué, which, inter alia, reconfirmed Belarus's commitment to the “One China policy.”

In 2011-2012, Minsk and Beijing signed and then ratified an agreement that launched, arguably, their most ambitious project – the Great Stone Industrial Park on the outskirts of Minsk. Its construction began in 2014. The countries declared that it would become China’s largest overseas industrial park. Later, the Great Stone secured the free customs zone status within the EAEU, which, in addition to the abolition of profit tax for the first ten years, made it particularly attractive for foreign investors. Besides its production capacity, the park was meant to become a logistical hub, a financial center, and even a residential area with the space to accommodate up to 200,000 people.

The project looked even more promising; as already in 2018 the contracted amount of investments of its residents reached $1 billion, coming not just from China and Belarus, but also Germany, Austria, the US, Lithuania, Russia, and other countries. Even more revealingly, the world’s biggest inland port, German Duisburger Hafen, acquired a shareholding in the Great Stone’s management company.

Following the establishment of the park, Belarus and China reached a series of agreements that further upgraded their relationship. In 2013, they signed a declaration on strategic partnership and a package of treaties in the areas of energy, industry, construction, and transport infrastructure worth about $3.5 billion. In May 2015, during President Xi’s stay in Minsk, the Friendship and Cooperation Agreement and a declaration on enhancing comprehensive strategic partnership were adopted.

Remarkably, in August 2015, President Lukashenko signed Directive No. 5 on the development of the relations with China. Presidential directives have a high status in the country’s legal hierarchy, and it remains the only such document focused on relations with a foreign country (normally, directives regulate domestic affairs). Among other things, the document required enlarging the number of specialists involved in the relations with China. The governmental export diversification strategy of 2016 also stressed the centrality of cooperation with Beijing.

Importantly, Chinese investments and joint projects were not limited to the industrial park only. For instance, Belarus and the Chinese automaker Geely established the joint venture motor company BelGee with ambitious plans to enter the EAEU markets. Another example was the Zoomlion-Maz factory producing automobile cranes with the largest lifting capacity ever built in Belarus. In a different realm, Chinese partners constructed the most powerful Belarusian hydropower station in Vitebsk in August 2018. In 2015, Chinese state and private entities expanded the program of attractive loans and funding for joint projects, when over $15 billion were made available.

Military cooperation also intensified significantly. In addition to multiple joint drills, anti-terrorist activities, and educational programs, Beijing expressed particular interest in the military-technical area, where Minsk traditionally has a lot to offer. Belarus, in its turn, looked for China’s help to strengthen its defense capacity. The Palanez multiple-launch rocket system (MLRS) has been the most outstanding example of the joint venture of the Belarus-China military industry since 2015.

However, the exponential growth of cooperation notwithstanding, the bilateral relations faced certain problems and challenges, especially for Belarus. Increasing trade volumes generated huge deficits for Minsk, as imports from China were outpacing Belarusian exports significantly. Beijing’s cheap loans, like in its other partnerships, were tied to strict conditions, which sometimes favored Chinese counterparts at the expense of Belarusian interests. In some cases, Minsk publicly criticized the quality of Chinese equipment and services and even terminated several projects.

Watershed Developments

The evolution of Belarus-China cooperation appeared set to continue in line with the linear logic that shaped it in the 2010s. However, the outbreak of the COVID pandemic brought an unexpected disruption to the overall logistical and supply chain designs at the center of the two countries’ partnership. That shock was followed by another watershed development, that is, the rapid and drastic worsening of Belarus’ relations with the West, and particularly the European Union. Massive Western sanctions following the 2020 presidential elections and especially after the start of the war in Ukraine, as well as the transport semi-blockade that the neighboring EU states imposed unilaterally on Belarus, clearly started to undermine the latter's logistical advantages and investment potential for China. Based on that, numerous commentators and Western diplomats expected that Belarus-Chinese cooperation and political ties would soon be curtailed. However, the reality proves to be different.

Continuing intense political dialogue, including the two visits President Lukashenko paid to Beijing in 2023, shows that the countries retain mutual interest in cooperation even under the significantly transformed geostrategic circumstances. Revealingly, in September 2022, they signed a declaration elevating their relationship to the level of an all-weather comprehensive strategic partnership. In the Chinese diplomatic hierarchy, this is the second highest level out of about 25 formats. While largely symbolic, the upgrade should not be dismissed as meaningless. Reflective of that, in March 2023, the countries signed about 40 agreements in fields as broad as banking and finances, agriculture and food production, construction, heavy industry, healthcare, sports and tourism, media, and academic cooperation. Between March and December 2023, more than 120 mutual visits on various governmental levels took place.

For Minsk, the importance of Beijing has only grown by 2020 due Western sanctions and political pressures. Belarusian officials are looking for ways of partially offsetting losses from the sanctions by augmenting exports and investment, financial, and production cooperation with Chinese counterparts. Politically, Minsk also needs enhanced relations with China to ensure that it has more breathing space in international affairs. Therefore, besides bilateral dealings, Belarus has activated diplomacy on multilateral platforms – like the Shanghai Cooperation Organization and BRICS – where China plays a key role.

The latest developments, including the improvement of the relations, imply that Beijing also continues to perceive Belarus as an attractive partner, irrespective of the currently adverse geopolitical processes around Belarus. Looking at the map, it is easy to see why. Even as Western sanctions are undermining Belarus's own potential, Beijing does not seem to have many alternative options for preserving its foothold in Eastern Europe and re-arranging its logistical network in the region. Ukraine is at war and will likely remain destroyed and destabilized for a long time. The “16/17+1” framework that China promoted for collaboration with Central and Eastern European nations is effectively dead now. Finally, Lithuania, which, due to its geography, could serve as a logistical gateway for China's access to the EU, refuses to follow the “One China policy” and is, hence, subjected to Chinese sanctions.

All this obviously keeps Belarus on Beijing’s strategic radar. The ongoing crises in the Middle East, and specifically the tensions in the Red Sea that are disrupting maritime transport communication between China and Europe, will strengthen the interest even further. While China-Europe freight train routes, where Belarus plays a crucial role, lack sufficient capacity to fully replace maritime transport, they can offer a critical alternative.

* Dr. Yauheni Preiherman is the founder and director of the Minsk Dialogue Council on International Relations (Belarus)

** This article was published as part of AVİM's partnership program. For AVİM’s partnership program, please click here.

***Picture: Belarusian and Chinese delegations meeting on 4 December 2023 – Source: Zhai Jianlan/Xinhua-AP

© 2009-2025 Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi (AVİM) Tüm Hakları Saklıdır

Henüz Yorum Yapılmamış.

-

TÜRKİYE-ERMENİSTAN İLİŞKİLERİ - DİPLOMATİK GÖZLEM - KASIM 2020

TÜRKİYE-ERMENİSTAN İLİŞKİLERİ - DİPLOMATİK GÖZLEM - KASIM 2020

Alev KILIÇ 05.11.2020 -

ABD BAŞKAN YARDIMCISI VANCE’IN GÜNEY KAFKASYA ZİYARETİ: STRATEJİK ORTAKLIK VE BÖLGESEL BAĞLANTI HAMLELERİ - ANADOLU AJANSI - 12.02.2026

ABD BAŞKAN YARDIMCISI VANCE’IN GÜNEY KAFKASYA ZİYARETİ: STRATEJİK ORTAKLIK VE BÖLGESEL BAĞLANTI HAMLELERİ - ANADOLU AJANSI - 12.02.2026

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 12.02.2026 -

THE POLITICIZATION OF GENOCIDE: IS THERE A GENOCIDE IN KARABAKH? - E-INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS - 20.09.2023

THE POLITICIZATION OF GENOCIDE: IS THERE A GENOCIDE IN KARABAKH? - E-INTERNATIONAL RELATIONS - 20.09.2023

Hakan YAVUZ 22.09.2023 -

SEÇİMİ HRİSOSTOMOS KAZANDI

Ata ATUN 17.02.2013 -

BULGARIA: AN UNLIKELY PERSONALITY CULT - NEW EASTERN EUROPE - 07.09.2018

BULGARIA: AN UNLIKELY PERSONALITY CULT - NEW EASTERN EUROPE - 07.09.2018

Tomasz Kamusella 10.09.2018