Şakir FAKILI(*)

United Nations (UN) have since 1948 adopted several resolutions to monitor, appease or settle conflicts at various parts of the world with peacekeeping forces totaling approximately seventy thousand field personnel. In essence, the overarching goal is to foster the necessary “conditions for lasting peace” in countries ravaged by conflict[1]. It is curious, however, to know whether all UN missions are as successful and innocent as we presume or whether corrections could be made if they fail or make things worse.

Former UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon stated in 2014 that the UN was ashamed of the peacekeepers’ conduct at the Rwanda Genocide of 1994. He admitted that the UN troops were withdrawn when they were most needed, and instead of overseeing national reconciliationü they only became eyewitnesses[2]. The outcome; 800,000 mostly ethnic Tutsis and moderate Hutus died at the hand of Hutu extremists. UN itself described its own record as "disgraceful" in its report of 1999.

Europe’s only acknowledged genocide since the Holocaust, committed against Muslim Bosnians in Srebrenica in 1995, took place in areas claimed "safe" by the UN, where Mr. Ban said, "Innocents were abandoned to slaughter".

Another such mission, the UN Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP), known as one of the oldest of UN endeavors, has a similar story of unprecedented bias against one of the people it is intended to protect. Known during the recent five decades as a force "protecting" a ceasefire line that has been incredibly quiet, it continues to antagonize the Turkish Cypriot people. This bitterness not only stems from its loss of impartiality on the ground, but is primarily rooted in the UN resolution that established its mandate.

Before it was destroyed, the Republic of Cyprus, founded by the London and Zurich Treaties of 1960, was based on a delicate balance drawn between Turkey and Greece by the Treaty of Lausanne in 1923. The 1960 Republic was a partnership state bringing the Turks and Greeks of the island together on equal terms. Based on this equality, it gave the Turks substantial rights, among others, the power of veto.

One of Cyprus Republic’s founding documents, the Treaty of Guarantee had given Turkey a significant right to intervene unilaterally in order to ensure the continuity of the 1960 state of affairs. With this Treaty Turkey was also able to send troops to the island for the first time since 1878, the year when British domination began. The Treaty brought the Turkish Cypriots a much longed for security benefit against the attacks of the Greek Cypriots.

However, it did not take long before this hard-won stability began to disturb the Greek Cypriot side. On 21 December 1963, the Greek Cypriots, with an aim to overthrow the established Republic and to unite the island with Greece, launched an overall armed attack against the Turkish population throughout the island. This ruthless aggression, known in history as "Bloody Christmas", caused the Turks more than 800 deaths. 103 Turkish villages were burned, their residents forced to flee. Turkish officials were forcefully expelled from the constitutional institutions, the government and the parliament. In a short time, the partnership state of Cyprus was converted into a Greek Cypriot entity. On 1 January 1964, Greek Cypriot leader Archbishop Makarios announced that he revoked all 1960 Treaties and the constitution, in a way the legitimacy of which is still disputed.

Britain’s efforts as former colonial power to seek reconciliation by having a meeting in London in January 1964 failed on account of Makarios' attempts to internationalize the problem. A conference was later convened in New York on 18 February at the UN Security Council. Talks ended on 4 March 1964 with the adoption of the infamous resolution number 186 (S/5575), which envisaged that the UN Peacekeeping Force to be set up to prevent bloodshed in Cyprus would operate under the approval of the Greek Cypriot Administration which acted as the "Government of the Cyprus Republic". Accordingly, it designated the Greek Cypriot side to be responsible for restoring law and order on the island. This meant that the fate of the Turks was handed over to their old "partner", meaning the fox was entrusted to safeguard the henhouse. This major flaw in the establishment of the Peace Force meant pouring gas into the Cyprus fire. Following this resolution, as expected, the Greek Cypriot attacks continued unabated. Worse, under watching eyes of the Peace Force, Greece managed to bring a total of 12,000 troops to the island between 1964 and 1967.

At the UN meeting held in New York, Britain’s priority was to maintain its influence and military presence on the island, not worrying much about the new structure of the government there. In fact, continued functioning of the British military bases depended more on cooperating with the Greeks than with the Turks[3]. Furthermore, aligning with the Greek cause had deep historical roots within British policy; in exchange for entering World War I, Britain had in 1915 offered its colony Cyprus as an inducement to Greece[4]. Obviously, the provocative role of Britain in Greece's occupation of Anatolia in 1919 is another well-known fact. Asked in 1964 if there existed a government in Cyprus after Bloody Christmas, Sir Francis Vallat, British Foreign Office official, replied "We have no information that there is no government"[5]. Further British attitude proved that Britain continued to behave as though the constitutional order on the island had not been broken. Apparently, Britain did not care much about the fate of the Turkish population.

The attitude of the United Nations was no different. In 1990, British MP Sir Anthony Kershaw ridiculed the contradictory landscape of that period: "The United Nations treated the Greek Cypriots as the one and only government. For them the legal basis for this was the Treaties (of 1960) and the constitution, which had been repudiated by the Greek Cypriot Government itself."[6]

What was the approach of the Turkish side? Mr. Rauf Denktaş, President of the then Turkish Communal Chamber, who was given the opportunity to speak at the Security Council to represent the Turkish Cypriots, stressed that, instead of sending a peacekeeping force to Cyprus, the guarantor countries should increase their troop contingents, as a valuable opportunity readily provided in the Guarantee Agreement[7]. Speaking about those days, Mr. Denktaş said that in New York he strongly opposed the draft resolution together with Turkey and managed to block it for one week. But the USA and Britain advised them not to stick to the word "government". He said they were trying to assure the Turkish side that what should be understood from the word "Government" was actually the bi-communal Government in line with the constitution!

When the attacks began, Turkey had wanted to exercise its right of intervention under the Treaty of Guarantee in order to save the lives of Cypriot Turks and prevent further bloodshed. Thus, the first USA draft to be submitted to the Security Council included, upon Ankara’s request, the view that Cyprus' independence stemmed from the London and Zurich Treaties and that such independence could only exist as long as these Treaties were in force. Greece and Makarios, on the other hand, were working hard to block this proposal through various maneuvers. The Archbishop, who was politically closer to the Non-Aligned Movement and the Soviet Union at the time, was not sparing any effort to get rid of especially the Guarantee Treaty. He therefore believed that if the issue could be addressed within the United Nations framework, he would have a wider scope for action. Turks, meanwhile, who were prevented from exercising their constitutional powers and forced out of state bodies, could attend Security Council meetings as private individuals while the Greek side continued to sit as a full member of the UN.

Final version of the Resolution 186 suited just what the Greek side wanted. Thus, the UN not only failed to condemn the usurpation of the constitution but also recognized the usurper as Government. Mr. Denktaş left the meeting at the edge of tears[8]. The Peace Force, which began operations in Cyprus with only face-saving neutrality was mostly a bystander, if not a tacit accomplice of the stronger side, while the Turks continued to face ruthless attacks.

Turkish Cypriot newspapers of the time[9] contained reports of horrible killings of Turks by Greek Cypriot men while UN forces were on duty. On 15 August 1974, like in Srebrenica, in the Turkish village of Taşkent, UNFICYP gathered the weapons of the villagers and handed them over to the Greek Cypriot police, causing 84 Turks aged 14 and over to be shot and killed by the Greek Cypriot gunmen[10]. What is more, residents of three Turkish villages, Atlılar, Muratağa and Sandallar, were all massacred and put in mass graves before the Turkish troops could reach their rescue during the second phase of the peace operation of the Turkish army that started on 14 August 1974. These crimes were committed when the Turkish delegation at the Geneva Peace Conference was desperately insisting that Turkish villages should be protected by the UN forces on the island and demanding the lifting of the Greek Cypriot blockade around these villages.

In the ensuing years, Resolution 186 dramatically distorted the perception of the Cyprus issue, emboldening the Greek Cypriot side to believe that they no longer needed a "settlement". At no cost, they continued to avoid the London and Zurich Treaties. Instead, they tried to pull all conciliatory talks to international grounds or to the UN, where great powers have veto power. For years, they generously used the title of "Government representing the Republic", while their old Turkish partners could only be represented at the table as "Community". As is the case with all negotiations where one party has unequal status, no tangible progress could be achieved. Prolonged talks led to the Turkish side being chained to the negotiating table and living in isolation for years. Resolution 186 was also used as a pretext in 2004 for Greek Cypriot administration's unfair accession to the European Union, contrary again to the 1960 arrangements which forbid Republic of Cyprus to join any international organization in which both Turkey and Greece are not members.

Thus, born with a partiality disputed by many for six decades, the UNFICYP has not been able to perform as an ideal instrument for peace and stability. Therefore, as political developments unfolded, it has become more of an entity open to question, if not always part of the problem, than a robust body trusted by all. It had aimed at its outset to prevent the so-called intercommunal strife, when even this labeling was widely disputed. As the conflict continued, it has become more and more evident that the root of the problem was actually somewhere else; there was a serious political conflict and ethnic cleansing, but it was ignored that one side of the conflict, namely the Greek Cypriots, had attacked the other side, destroyed their common state and threw out their Republic’s co-founder from all constitutional bodies by force of arms.

This way the UN Force, meant at the start to protect the law and order in the island, started to function under the terms dictated by the victimizer.

Another likely reason why this resolution failed to bring any settlement in Cyprus was the wish of great powers to shape, according to their individual strategic thoughts, an issue which could have been settled far more easily if parties to the conflict could at good will adhere among themselves to the 1960 Agreements that formed the Republic and were efficient tools at the disposal of all concerned.

Therefore, quite understandably, the long history of the UNFICYP is not in short supply of allegations of being one sided. Both Ankara and the Turkish Cypriots brought their complaints to the UN[11], but, while the UNFICYP watched, the Turkish Cypriots suffered enormous human and material losses between 1963 and 1974 under the attacks of the Greek Cypriot side.

To better understand the situation, it must be revealing to know that 33% of the UN Peacekeeping Force's budget is still paid by the Greek Cypriot administration and 11% by Greece. Today, the Peacekeeping Force does not have jurisdiction over the territory of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. A status of forces agreement does not exist with the Turkish side. After 1974 Turkish Cypriots have successfully established their own security under the roof of their own state. For the UN, though, with so much blunder caused by Resolution 186, the Cyprus issue still remains as an unresolved one.

One incident of biased UN action took place recently on 18 August 2023, when United Nations peacekeepers attempted to block the construction of a road to connect two neighboring villages having Turkish populations, namely, Pile in the Buffer Zone and Yiğitler at the territory of the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus. Notably, Pile is also home to Greek Cypriots.

Previously, a road construction from the Greek Cypriot side to Pile had been connived by the United Nations. Now, however, a similar move of the Turkish side met a UN blockade. It was at first sight hard to understand why a UN force that everybody thinks is responsible for peace and prosperity acted in a discriminatory way and obstructed a humanitarian move. The answer leads us again back to Resolution 186, which has been one of the root causes of injustice to date against the Turkish Cypriot people. It is the reason for a series of distortions, misconceptions, and wrong doings around the Cyprus issue.

So how could such an unfair decision be taken in the United Nations Security Council?

Basically, everyone who watches Cyprus closely knows that the real peace and security on the island has been provided by another peacekeeping force, the Turkish military, since 1974.

Perhaps another UN resolution is needed to correct the foregoing misconceptions of the past six decades. Consequently, the UN should seriously reconsider the paradox it has created on the island with an ineffective and impotent military unit. The international community as well should be aware that the Greek Cypriot Administration of Southern Cyprus is the only EU country with a peace keeping force on its territory and the only one that exists with an unresolved political conflict.

* Ret. Ambassador who previously served as Türkiye’s Ambassador to Lefkoşa/Nicosia – the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus

** Image: A member of the UN Peacekeeping Force in the island of Cyprus looks at a map of the buffer zone between the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus and the Cypriot Greek Administration of Southern Cyprus – Source: Business Insider

[1] ”Peace Begins with Me”, United Nations Peacekeeping, https://peacekeeping.un.org/en

[2] “Rwanda Genocide: UN Ashamed Says Ban ki-moon”, BBC News, 7 April 2014.

[3] Michael Moran, Resolution 186, Its Genesis and Significance, Nicosia, CYREP, 1999, p. 35.

[4] Paul Helmreich, From Paris to Sèvres, Columbus, Ohio State University Press, 1974, p. 40.

[5] Salahi R. Sonyel, Cyprus, The Destruction of a Republic and Its Aftermath, British Documents 1960-1974, Lefkoşa, CYREP, 2003, p. 73.

[6] Ibid., p. 75.

[7] Moran, ob. cit, p.5.

[8] Ibid., p. 13.

[9] “Birleşmiş Milletler Barış Gücünün Görev Başında Olmasına Rağmen Rumlar Dün 4 Türk’ü Kurşuna Dizdi (Despite the Presence of United Nations Peace Force, Greek Cypriots Gunned Down 4 Turks)“, Bozkurt (Turkish Cypriot daily), 8 April 1964.

[10] “Taşkent Katliamı ve Şehitlerimize Sahip Çıkmak (Massacre of Taşkent, We Must Uphold Our Devotion to Our Martyrs)”, Kıbrıs (Turkish Cypriot daily), 17 August 2023.

[11] “Turkey Protests to UN on Cyprus; Sees a Danger to Peace in Greek Cypriot Attacks on Turkish Community”, The New York Times, 21 April 1964.

© 2009-2025 Avrasya İncelemeleri Merkezi (AVİM) Tüm Hakları Saklıdır

Henüz Yorum Yapılmamış.

-

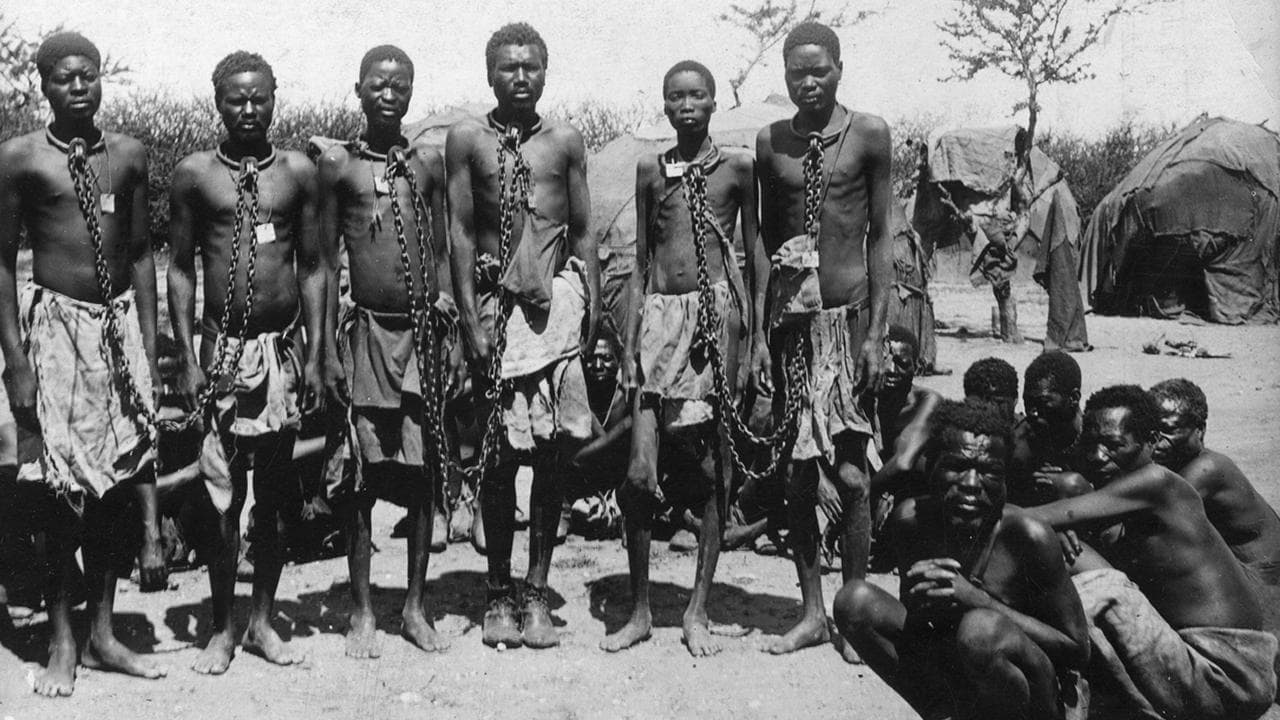

NAMİBYA’DA SOYKIRIM YAPAN ALMANYA’YA KARŞI NEW YORK MAHKEMESİ’NDE AÇILAN TAZMİNAT DAVASI DEVAM EDİYOR - T24 - 08.08.2019

NAMİBYA’DA SOYKIRIM YAPAN ALMANYA’YA KARŞI NEW YORK MAHKEMESİ’NDE AÇILAN TAZMİNAT DAVASI DEVAM EDİYOR - T24 - 08.08.2019

Hasan Servet ÖKTEM 15.08.2019 -

SİYASİ KRİZ İÇİNDE ARNAVUTLUK

Erhan TÜRBEDAR 05.05.2010 -

“TÜRKİYE’DEKİ ERMENİ GÖÇMENLERİN DURUMU” KONULU TOPLANTIYA DAİR

Oya EREN ÖZER 16.02.2010 -

BMGS GUTERRES’İN 5+1 KIBRIS KONFERANSI HAKKINDAKİ AÇIKLAMASI VE DEĞERLENDİRME - 31.01.2021

BMGS GUTERRES’İN 5+1 KIBRIS KONFERANSI HAKKINDAKİ AÇIKLAMASI VE DEĞERLENDİRME - 31.01.2021

Tugay ULUÇEVİK 03.02.2021 -

UN REPORT ON MYANMAR REVEALS THE GENOCIDAL INTENT AGAINST ROHINGYA MUSLIMS - DAILY SABAH - 03.10.2018

UN REPORT ON MYANMAR REVEALS THE GENOCIDAL INTENT AGAINST ROHINGYA MUSLIMS - DAILY SABAH - 03.10.2018

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 05.10.2018