China's "preventive" security mechanisms are based on identifying individuals who are deemed to be prone to crime and implementing the necessary actions concerning them. After China's transition to a market economy, China needed "preventive" security practices after an increase in social unrest due to reasons such as the loss of the function of the neighborhood committees in the working units (danwei), the development of communication tools, the increase in mobility etc. We will discuss four of these “preventive” security mechanisms in our article.

The Grid Management System (Wanggehua Guanli)

The grid management system is conducted by dividing urban areas into a number of grids in digital maps and assigning controllers to each grid.[1] The supervisor, who is a resident of that region, reports the problems in the region and the situations he deems "suspicious" to the public officials via the provided mobile device.[2] In addition, supervisors are expected to regularly submit information about a certain number of households to the determined authority.[3] Thus, it is aimed to solve problems quickly and prevent crime. Records of previous events in each grid are also archived electronically.[4]

This system, which was first applied in the Dongcheng district of Beijing in 2004, has become widespread throughout China and is carried out in rural areas as well as cities. How much area each grid covers depends on the geographical area. It is stated that the grid management system is useful for fast detection and solution in cases such as lost manhole covers in cities, damage to public facilities, garbage dumping, as well as functional for ensuring public safety.[5]

In terms of security, one reason why China has created the grid system is that the neighborhood committees are no longer functional. Neighborhood committees were created as a grassroot organization in 1952. Under the household registration system (hukou), in work units (danwei) where education and health services, housing and work were carried out in a single unit, neighborhood committees played role in monitoring people, acting as an intermediary for the provision of control and political education.[6] However, after China’s transition to a market economy, urbanization and mobility increased, and those who did not want to work in danweis, who wanted to work in the places they chose, and illegal immigrants increased.[7] Therefore, the grid management system responded to the need to manage and control the consequences of the dissolution of production-oriented communities and the increasing mobility of the population in China.

Besides, the fact that these supervisors ("auxiliary public order officials", as author Zhou Wang calls them) do not have fixed working hours, are only responsible for reporting suspicious things to the authorities, and that they thus receive a small salary of 300 to 500 yuan (50 to 80 dollars) a month enables the Chinese state to devote less resources to police employment as public servants.[8]

The most important function of the grid management system is social control. For example, in 2008, in the Dai-Lahu-Va Autonomous County of Menglian in Yunnan province, where the majority of the Dai ethnic group live, rubber farmers had started protests against the rubber company they worked for and this had turned into clashes with the police. After these events, it had been decided to implement the grid management system in this region.[9] Furthermore, as Wu Qiang points out, just after the Jasmine Revolution broke out, the President of that period, Hu Jintao, called for finding innovative ways of carrying out social management. The implementation of the grid management system by portraying it as a social management innovation reveals the security dimension of this system.[10]

During the period of Chen Quanguo, who was the general party secretary between 2011 and 2016 in Tibet, the grid management system started to be implemented in Tibet.[11] Later, after being appointed as party secretary in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region (XUAR) in 2016, Chen drew on his experience in Tibet and ensured the establishment of a grid management system in this region and increased security measures with other applications.[12]

The Social Credit System

The Social Credit System (SCS), which was established as a commercial credit rating system, was later expanded as a system which also scores the social behavior of the citizens. It was announced that the credit system for scoring citizens' social behavior, which is being evaluated in pilot projects, is planned to be implemented throughout China.[13]

In 2014, the State Council of China issued a plan under the name “Planning Outline for The Construction of a Social Credit System.” This notice calls on local authorities, ministries, and commissions to establish a full-scale SCS.[14] Following this call of the State Council, local authorities have created pilot projects and several companies, including technology companies, have created joint projects with the government. For example, according to a study by Martin Maurtvedt on the SCS, the government and the private sector acted together in the Honest Shangai Project, and people could see their scoring via a smart phone app based on criteria such as whether they paid their bills on time.[15] The Alibaba company’s “Sesame Credit” project carried out evaluations by observing people’s shopping habits and its website provided advantages to high-credit people.[16] Some applications such as these that resemble games have had significant effects on people's private lives. For example, people with low scores have been banned from traveling by plane.[17]

Genia Kostka, who surveyed public opinion in China about the Social Credit System, expected before starting her research that educated, urban people who have high-income would have had a more liberal understanding, and would thus approach to SCS with suspicion.[18] However, her research has shown the opposite. It has been observed that people with higher income support the system more than people with low income and that those living in cities support the system more than those living in rural areas.[19] The researcher concluded that sections of the population who think that they stand to benefit from this system show support for it.[20] It is also noted that ethnic minorities approach SCS with suspicion.[21]

According to a report by Human Rights Watch, it is stated that in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, people with links to one of "26 sensitive countries" (including Kazakhstan, Turkey, Malaysia, Indonesia) are categorized as "suspects". Alongside this, individuals who have “abnormal” beards or religious names are considered "suspects" on the grounds that they are prone to separatism and extremism.[22] Detention of “risky” individuals in re-education camps and subjecting them to indoctrination justifies the suspicions of minorities concerning the Social Credit System.

Re-education Camps

The re-education camps are the most radical example of preventive security practices. Initially, Chinese officials had stated to the world public that these centers were vocational training centers.[23] However, after the legalization of these centers, it was revealed that they enact anti-extremist ideological education.[24]

In August 2018, in the session of the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination in China, Gay McDougall asked about the detention and disappearance of Uyghur students returning from abroad.[25] In July 2019, 22 countries (Australia, Austria, Belgium, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, Japan, Latvia, Lithuania, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and the UK) wrote a letter to the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights calling China to end the detentions.[26] This issue has thus become the focus of the world agenda, and Human Rights Watch has published a comprehensive report on re-education camps.[27]

The origins of the concept of "re-education" go back to earlier times in Chinese history. The first modern prisons were established in the modernization process of China at the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. While modern prisons seen in the West started to be implemented in the same way, and in addition to this, in connection with the Confucian theory, the importance of moral improvement and education in prisons was emphasized. It was stated that the crime was a disease, and prisons would provide education and transformation and would thus play the role of a hospital.[28] However, Sinologist Klaus Mühlhahn, who has studied the penal system in China, states that due to Confucius' distrust of law, re-education in prisons is not related to Confucius's views, but his idea of reintegrating people into society through education has been instrumentalized in the process of modernization.[29] Mühlhahn also states that rather than moral education, political indoctrination is carried out in re-education.

We also see the re-education practice in the 1930s, where the political opponents of the Guomindang (Nationalist Party of China) were detained in mass internment camps.[30] In these camps, inmates were called “people in self-cultivation” or “convalescents.”[31] Practices such as Confucian moral thinking and examinations through individual discussions, and self-cultivation reports were implemented to persuade inmates to “correct” their thinking.[32] At the time of the Guomindang, the Soviet corrective labor practices in prisons were also cited as a model.[33] In the 1950s, in the framework of reform through labor in prisons, there were prisons which functioned almost as factory camps.[34]

The difference of the current re-education camps is that suspects are arrested as a preventive security mechanism simply because they represent a “risk”. For example, around 8000 Tibetan people who attended the religious ceremony the Kalachakra religious ceremony in India were detained for “re-education” when they returned.[35] In the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, it is claimed that approximately 1 million people are detained in re-education camps. The "Xinjiang Victims Database" published on the Shahit.biz website, which is founded by Gene Bunin, documents the situation of more than 10,000 people in camps, prisons, or in police custody based on interviews with their families.[36] Kazakhstan-based human rights organization, Atajurt Kazakh Human Rights[37], has been broadcasting with the testimonies of Uyghur Turks, Kazakh Turks, and other ethnic groups in the region and has provided a lot of information about re-education camps.[38]

With the US-China rivalry intensifying, news about arrests in re-education camps is receiving more coverage in the West. On the other hand, it is noted that the Frontier Services Group (FSG), led by Erik Prince, the founder of the notorious private security company Blackwater that was known for the crimes it committed in Iraq, has worked to train counter-terrorism personnel in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region.[39] Also, the report of the Australian Strategic Policy Institute, of which Vicky Xiuzhong Xu is the lead author, claimed that companies, including well-known western brands, were involved in the supply chain of factories which used forced labor of Uyghur Turks as part of re-education.[40] These raise doubts about the western supporters of these practices, contrary to what appears in the media.

We should note that as the reactions of the international public have increased, the number of arrests in re-education camps has decreased recently. However, in place of arrests in re-education camps, it is reported house arrest and forced labor practices have been introduced[41] and that China’s focus has shifted more to the transfers of inmates to prisons.[42]

Home Visits

Another “preventive” security and surveillance practice is home visits by government officials and party members.[43] First, in 2014, under the program of “Visit the People, Benefit the People, and Bring Together the Hearts of the People”, 200,000 party members visited homes in Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region,[44] expressing the aim of listening to the voice of the people and solving the difficulties of their lives.[45]

In 2016, under the program of “Becoming Family”, 110,000 officials visited the rural areas of the region.[46] In 2017, this campaign was expanded, and more than 1 million officials spent a week at a time in the homes of Uyghur and Kazakh families.[47] In 2018, this was converted to regularly visits every two months.[48]

However, Daren Byler states in his research that, according to the manuals provided by the government, the officials visiting houses are responsible for detecting "suspicious situations" and implementing political indoctrination.[49] The author claims that these families are visited especially if a family member is detained at a re-education center.[50]

*Photograph: The New York Times

[1] Wu Qiang, “Urban Grid Management and Police State in China: A Brief Overview”, China Change, August 12, 2014, https://chinachange.org/2013/08/08/the-urban-grid-management-and-police-state-in-china-a-brief-overview/

[2] Wu Qiang, “Gridding, Mass Line and Social Management Innovation, A Comparative Study of Gridding Management in China from an Anthropological-Political Perspective”, The China Nonprofit Preview, 7(1), 2015, p. 121.

[3] Yongshun Cai, “Grid Management and Social Control in China”, The Asia Dialogue, April 27, 2018, https://theasiadialogue.com/2018/04/27/grid-management-and-social-control-in-china/

[4] Wu Qiang (2015), p. 121.

[5] Yan Yaojun, 城市网格化管理的特点及启,《城市问题》年第 2 期, 2006, p. 76.

[6] Allen C. Choate, “Local Governance In China -Part II, An Assessment Of Urban Residents Committees And Municipal Community Development”, The Asia Foundation Working Paper Series, Working Paper No. 10, 1998, p. 8-9.

[7] Lisa M. Hoffman, “The Urban, Politics And Subject Formation”, International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 38(5), 2014, p. 1581.

[8] Zhou Wang, “Is China’s Grassroots Social Order Project Running Out of Money?”, Sixth Tone, June 1, 2018, https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1002393/is-chinas-grassroots-social-order-project-running-out-of-money%3F

[9] Shu-Wang Zhang, Can Guo and Jeff Wang, “The Improvement of Grid Management in Rural Community from the View of Social Governance-Based on the Investigation of Menglian”, International Conference on Advanced Education and Management Science, 2017, p. 159.

[10] Wu Qiang (2015), p. 112.

[11] “The Origin of the ‘Xinjiang Model’ in Tibet under Chen Quanguo: Securitizing Ethnicity and Accelerating Assimilation”, International Campaign for Tibet, December 19, 2018, https://savetibet.org/the-origin-of-the-xinjiang-model-in-tibet-under-chen-quanguo-securitizingethnicity-and-accelerating-assimilation/

[12] Sophie Richardson, (2017), “China Poised to Repeat Tibet Mistakes”, Human Rights Watch, January 20, 2017, https://www.hrw.org/news/2017/01/20/china-poised-repeat-tibet-mistakes

[13] Fan Liang, Vishnupriya Das, Nadiya Kostyuk, and Muzammil M. Hussain, “Constructing a Data-Driven Society: China’s Social Credit System as a State Surveillance Infrastructure”, Policy & Internet, 10(4), 2018, p. 416.

[14] “Planning Outline for the Construction of a Social Credit System (2014-2020)”, China Copyright and Media, June 2014, https://chinacopyrightandmedia.wordpress.com/2014/06/14/planning-outline-for-the-construction-of-a-social-credit-system-2014-2020/

[15] Martin Maurtvedt, “The Chinese Social Credit System Surveillance and Social Manipulation: A Solution to “Moral Decay?”, Master’s Thesis, Department of Culture Studies and Oriental Languages, University Of Oslo, 2017, p. 23.

[16] Ibid, p. 24.

[17] Simina Mistreanu, (2019), “Fears About China’s Social-Credit System Are Probably Overblown, But It Will Still Be Chilling”, the Washington Post, March 8, 2019, https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2019/03/08/fears-about-chinas-social-credit-system-are-probably-overblown-it-will-still-be-chilling/

[18] Genia Kostka, “China’s Social Credit Systems And Public Opinion: Explaining High Levels Of Approval”, New Media & Society, 21(7), 2019, p. 1579.

[19] Ibid, p. 1577.

[20] Ibid, p. 1579.

[21] Maurtvedt (2017), p. 35.

[22] Human Rights Watch, “Eradicating Ideological Viruses, China’s Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang’s Muslims”, HRW, September 9, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/report_pdf/china0918_web.pdf

[23] “China Denies Having 'Concentration Camps,' Tells US to 'Stop Interfering'”, CNN, May 6, 2019, https://edition.cnn.com/2019/05/06/asia/china-us-xinjiang-concentration-camps-intl/index.html

[24] “China Legalizes Xinjiang 'Re-education Camps' After Denying They Exist”, CNN, October 11, 2018, https://edition.cnn.com/2018/10/10/asia/xinjiang-china-reeducation-camps-intl/index.html

[25] Nick Cumming-Bruce, “U.N. Panel Confronts China Over Reports That It Holds a Million Uighurs in Camps”, the New York Times, August 10, 2018, https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/10/world/asia/china-xinjiang-un-uighurs.html

[26] ”Joint Statement”, Human Rights Watch, July 8, 2019, https://www.hrw.org/sites/default/files/supporting_resources/190708_joint_statement_xinjiang.pdf

[27] “Eradicating Ideological Viruses, China’s Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang’s Muslims”

[28] Klaus Mühlhahn, Criminal Justice in China: A History, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts and London, England, 2009, p. 80.

[29] Ibid, p. 75.

[30] Klaus Mühlhahn, “The Concentration Camp in Global Historical Perspective”, History Compass, 8(6), 2010, p. 551.

[31] Ibid, p. 553.

[32] Ibid, p. 553.

[33] Mühlhahn (2009), p. 79.

[34] Adrian Zenz, “Thoroughly Reforming Them Towards a Healthy Heart Attitude: China’s Political Re-education Campaign in Xinjiang”, Central Asian Survey, 38(1), 2018, p. 3.

[35] “Lockdown in Lhasa At Tibetan New Year; Unprecedented Detentions Of Hundreds Of Tibetans After Dalai Lama Teaching in Exile”, International Campaign for Tibet, February 22, 2012, https://savetibet.org/lockdown-in-lhasa-at-tibetan-new-year-unprecedented-detentions-of-hundreds-of-tibetans-after-dalai-lama-teaching-in-exile/

[36] Xinjiang Victims Database, https://shahit.biz/eng/

[37] Atajurt Kazakh Human Rights Facebook Page, https://www.facebook.com/kazakhrights/

[38] Mehmet Volkan Kaşıkçı, “Documenting the Tragedy in Xinjiang: An Insider’s View of Atajurt”, The Diplomat, January 16, 2020, https://thediplomat.com/2020/01/documenting-the-tragedy-in-xinjiang-an-insiders-view-of-atajurt

[39] Gerald Roche, “Transnational Carceral Capitalism in Xinjiang and Beyond”, Made in China Journal, February 12, 2019, https://madeinchinajournal.com/2019/02/12/transnational-carceral-capitalism-xinjiang/

[40] Gülperi Güngör, “Factorıes Usıng Forced Labour Of The Uyghurs …”, AVİM, March 9, 2020, https://avim.org.tr/en/Yorum/FACTORIES-USING-FORCED-LABOUR-OF-THE-UYGHURS-PROVIDE-SUPPLIES-FOR-83-WELL-KNOWN-BRANDS

[41] Chris Rickleton, Mehmet Volkan Kaşıkçı, “Kazakh family of writers and musicians caught in the Xinjiang vortex”, Global Voices, January 22, 2020, https://globalvoices.org/2020/01/22/kazakh-family-of-writers-and-musicians-caught-in-the-xinjiang-vortex/

[42] Gene A. Bunin, “From camps to prisons: Xinjiang’s next great human rights catastrophe”, Living Otherwise, October 5, 2019, https://livingotherwise.com/2019/10/05/from-camps-to-prisons-xinjiangs-next-great-human-rights-catastrophe-by-gene-a-bunin/

[43] "Eradicating Ideological Viruses, China’s Campaign of Repression Against Xinjiang’s Muslims”

[44] Human Rights Watch, “China: Visiting Officials Occupy Homes in Muslim Region”, HRW, May 13, 2018, https://www.hrw.org/news/2018/05/13/china-visiting-officials-occupy-homes-muslim-region

[45] People's Daily Online http://xj.people.com.cn/GB/188750/361873

[46] “China: Visiting Officials Occupy Homes in Muslim Region”

[47] Ibid.

[48] Ibid.

[49] Darren Byler, “Violent Paternalism: On the Banality of Uyghur Unfreedom”, The AsiaPacific Journal, 16(24), 2018, p. 5

[50] Ibid, p. 4.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

TURKIC COOPERATION IN THE CENTER OF EURASIA: THE TURKIC COUNCIL

TURKIC COOPERATION IN THE CENTER OF EURASIA: THE TURKIC COUNCIL

Gülperi GÜNGÖR 05.02.2021 -

BOOK REVIEW: “ARMENIA’S FUTURE, RELATIONS WITH TURKEY, AND THE KARABAGH CONFLICT”

BOOK REVIEW: “ARMENIA’S FUTURE, RELATIONS WITH TURKEY, AND THE KARABAGH CONFLICT”

Gülperi GÜNGÖR 11.02.2020 -

MONGOLIA’S SEARCH FOR BALANCE IN ITS FOREIGN POLICY

MONGOLIA’S SEARCH FOR BALANCE IN ITS FOREIGN POLICY

Gülperi GÜNGÖR 28.08.2020 -

TRANSPORTATION PROJECTS IN CAUCASIA

TRANSPORTATION PROJECTS IN CAUCASIA

Gülperi GÜNGÖR 27.05.2021 -

CHINA’S INFLUENCE IN CENTRAL ASIAN TRADE

CHINA’S INFLUENCE IN CENTRAL ASIAN TRADE

Gülperi GÜNGÖR 08.06.2020

-

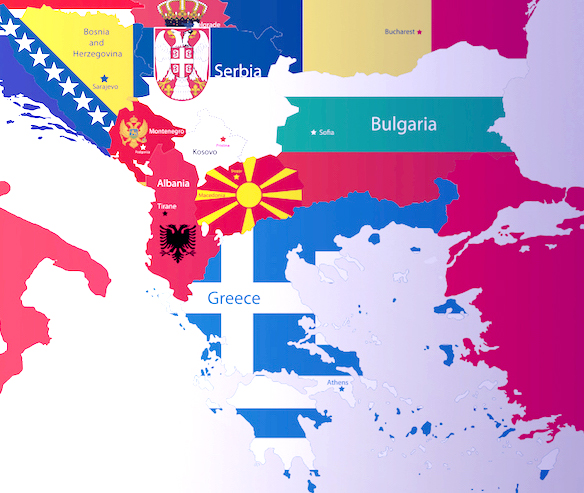

CHAILLOT PAPER ON BALKANS FUTURE: A CASE OF ILL-INFORMED LEADING THE ILL-INFORMED

CHAILLOT PAPER ON BALKANS FUTURE: A CASE OF ILL-INFORMED LEADING THE ILL-INFORMED

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 02.10.2018 -

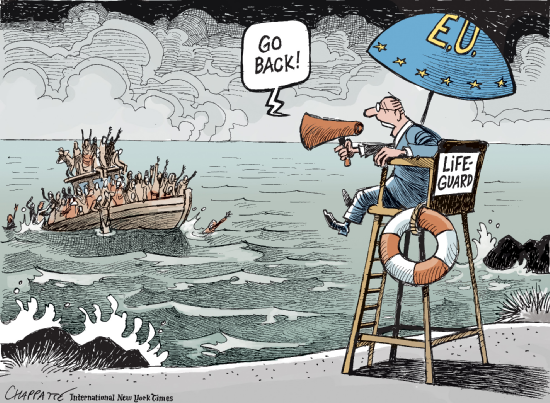

HOW DOES VON DER LEYEN'S DESCRIPTION OF “EUROPEAN WAY OF LIFE” COMPLY WITH EUROPEAN VALUES?

HOW DOES VON DER LEYEN'S DESCRIPTION OF “EUROPEAN WAY OF LIFE” COMPLY WITH EUROPEAN VALUES?

AVİM 30.09.2019 -

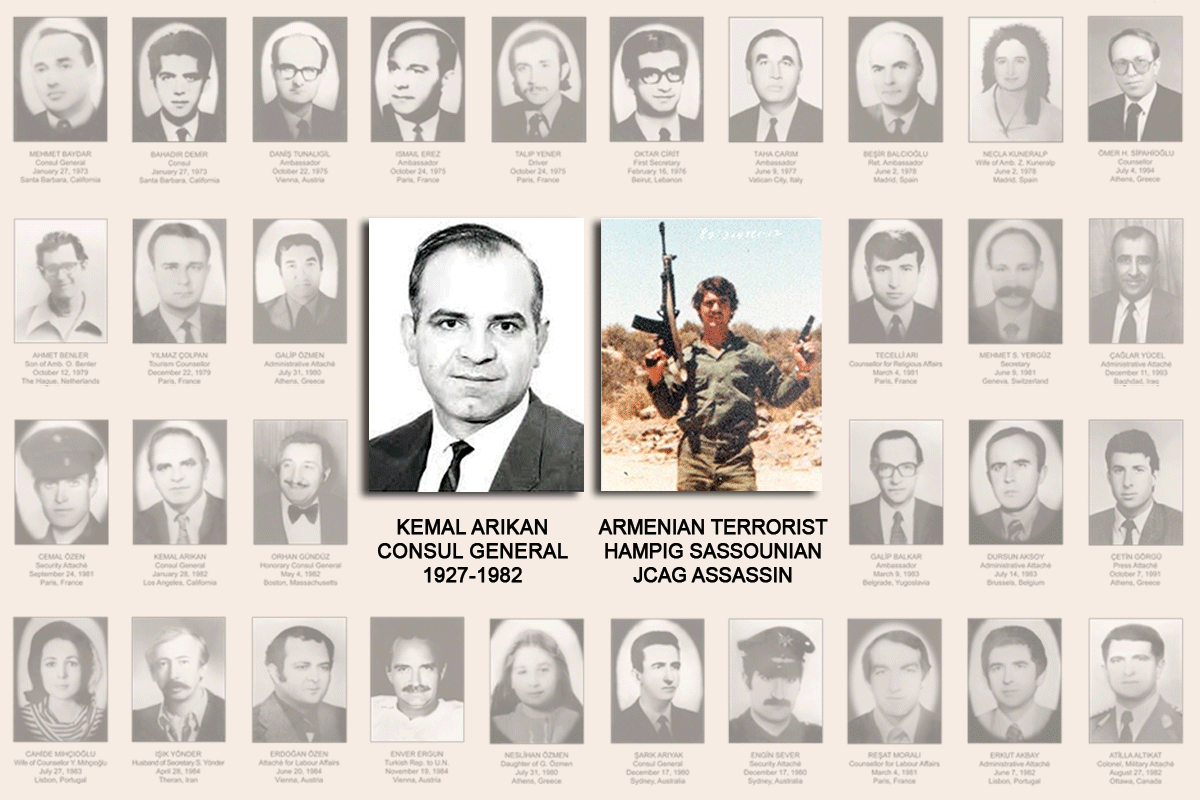

THE DECISION TO RELEASE SASSOUNIAN

THE DECISION TO RELEASE SASSOUNIAN

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 16.03.2021 -

1934 PACT OF BALKAN ENTENTE: THE PRECURSOR OF BALKAN/SOUTHEAST EUROPE COOPERATION

1934 PACT OF BALKAN ENTENTE: THE PRECURSOR OF BALKAN/SOUTHEAST EUROPE COOPERATION

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 06.08.2020 -

BLACK SEA NEEDS CONFIDENCE AND SECURITY BUILDING MEASURES MORE THAN EVER

BLACK SEA NEEDS CONFIDENCE AND SECURITY BUILDING MEASURES MORE THAN EVER

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 30.10.2018

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"