The characteristics of the previous works of Taner Akçam are well-known by those who are acquainted with the Armenian question.

Nevertheless, Akçam continues to present these works and claims that are full of distortions and lies as if they are newly-discovered documents and information.

Previously, claims by Akçam were refuted and distortions exposed with a detailed analysis written by AVİM Honorary President Ömer Engin Lütem that was published in Ermeni Araştırmaları (İssue 55) and Review of Armenian Studies (Issue 34) titled “An Assessment on Aram Andonian, Naim Efendi and Talat Pasha Telegrams” (Aram Andonyan, Naim Efendi ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları Üzerine Bir Değerlendirme).

However, it is seen that Akçam’s propagandist works continue to be published by the support of Armenians and those who support Armenian claims.

Thus, as AVİM, we share this valuable work by Ömer Engin Lütem again to inform the public and to remind and warn them of the baseless claims and distortions presented in these publications.

We continue to believe this analysis by Lütem still holds great importance to learn the truth through objective and academic works, and not distortions, and to advise those who are not knowledgeable about this issue not to give credit to smear and defamation campaign.

BOOK REVIEW

AN ASSESSMENT ON ARAM ANDONIAN, NAIM EFENDI AND TALAT PASHA TELEGRAMS

REVIEW OF ARMENIAN STUDIES

ISSUE:34

Taner Akçam – Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları, Krikor Gergeryan Arşivi

İletişim Yayınları, İstanbul, 2016, 278 Sayfa.

Ömer Engin LÜTEM

In his book titled Naim Efendi’nin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları (En. The Memoirs of Naim Efendi and Talat Pasha Telegrams) (İletişim Yayınları, 2016), Taner Akçam argues that the telegrams and documents that were published 96 years ago by Aram Andonian and which are attributed to several high-ranking Ottoman officials, particularly Minister of the Interior (Tr. Dâhiliye Nazırı) Talat Pasha, are in fact real and authentic. Akçam’s main argument is based on the claim that the book Ermenilerce Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü (En. The Talat Pasha Telegrams: Historical Fact or Armenian Fiction?) by Şinasi Orel and Süreyya Yuca, which was published in 1983 and puts forward concrete arguments on the forged nature of the above-mentioned documents, is full of errors and that their accusations with regard to the documents are unjustified.

According to Akçam, contrary to Orel’s and Yuca’s claims, there was an Ottoman official by the name of Naim Efendi, it was him who provided Andonian with the documents, and the memoirs published by Andonian was personally written by Naim Efendi. Accordingly, Akçam claims that an official by the name of Naim Efendi is spoken of in three documents that he claims to be Ottoman archival documents. Furthermore, Akçam publishes in his book memoirs that he found in the personal papers of Krikor Guerguerian and which he claims to have been written by Naim Efendi. According to Akçam, Krikor Guerguerian found these memoirs in the Nubarian Library located in Paris.

At this juncture, let us state that there is no evidence (name, signature, initials, date etc.) indicating that these memoirs were actually written by Naim Efendi. Furthermore, even if the memoirs were in fact written by Naim Efendi, there is no information on whether changes were made on the text or whether the text was subsequently edited by someone or some people. In objective sources for which there is no dispute, there are no samples of the handwriting of the so-called Naim Efendi, and therefore, there is no possibility to compare them with the handwriting in the published memoirs. Also, the text of the supposed memoirs does not resemble the texts of classically what we know as “memoirs”. The said memoirs do not provide a narration of Naim Efendi’s role during the events, his dialogues with others, and the chronology of events. It provides texts that is alleged to be official correspondences and includes occasional commentaries on these correspondences. The aforementioned events are presented in a convoluted manner and the text does not follow a chronological narration. For instance, telegrams dated September 1915 are provided following telegrams dated January 1916, and this continues to be the case throughout the text of the memoirs. Again, a telegram dated February 1917 is followed by other telegrams dated 1915 and 1916. Moreover, throughout the text, there is no indication on what Naim Efendi’s duty was and where he served. In this respect, as mentioned above, the text does not resemble texts of standard memoirs, and gives the impression that it was written per order.

The text published by Akçam is also glaringly different from the text of the memoirs published by Andonian in 1920. For instance, while the text published by Andonian contains statements about the places where and position in which Naim Efendi served, no such statements are contained in the text published by Akçam. Thus, the first suspicion that comes to mind is that the text might have been changed by Andonian for his self-interests (and by the Armenian Bureau in London and the Armenian National Delegations in Paris who made changes on the text as mentioned by Andonian in one of his letters). However, Akçam, who is completely convinced of the authenticity Andonian’s narrative and his published documents, does not consider and discuss this possibility. Akçam, who puts Andonian on a pedestal and insists on the authenticity of Andonian’s narrative, explains this situation with the assumption that there must be another sample of the memoirs other than the ones published by Andonian. In other words, according to Akçam, another text exists besides the memoirs published by him; it was this text that was published by Andonian, and this is the reason why there are two different texts. However, Akçam is unable to provide any evidence or indication supporting this possibility. As a matter of fact, it is actually this approach by Akçam that constitutes the book’s main problem. In fact, in cases where there is no evidence to prove the authenticity of these documents, Akçam tries to dispel inconsistencies and suspicions by making an assumption on top of another assumption.

It must be noted that Andonian’s explanations and comments on different dates about same events and people contradict with each other, and therefore it is quite problematic to accept Andonian’s statements as fact in terms of historiography. For instance, Andonian depicted the so-called Naim Efendi as a kind-hearted and charitable person, and wrote that Naim Efendi, despite his poor financial situation, provided him with these documents without expecting anything in return simply to ease his own conscience.[1] However, in a letter he wrote in 1937, he describes Naim Efendi as “an alcoholic and gambler” and “an entirely dissolute creature”, and states that the documents were acquired from Naim Efendi in return for money.[2]

Similarly, Andonian, in his letter dated 1937, claims that the authenticity of the documents he published were confirmed by the German Court in Berlin in 1921 during the trial of Soghomon Tehlirian who had assassinated Talat Pasha. However, when the proceedings of the court are checked, it can be seen that this is not the case. According to the court proceedings, despite Tehlirian’s attorney’s request to submit five documents from Andonian to the court, it is seen that he dropped his request following German prosecutor’s objections. According to the prosecutor, it was not for the court to decide whether Talat Pasha was guilty or not, and such determination necessitated a historical research. This effort necessitated the examination of materials different from those that were present. According to the prosecutor, the fact that the accused Tehlirian had been convinced of Talat Pasha’s guilt was sufficient in terms of revealing Tehlirian’s intention to murder him. In the face of these objections, Tehlirian’s attorney Adolf von Gordon abandoned the request to submit the documents to the court.[3] Furthermore, during the trial in Berlin, the prosecutor had a distanced and reserved approach towards these documents, and had taken into consideration the possibility that they could be forged:

The use of the forged documents cannot also lead me into error… I am familiar with the history of how, in the chaos of the revolution, we came to possess documents bearing the signatures of high ranking individuals, and how it was subsequently proved that they were forged.[4]

At this juncture, it should be stated that these comments by the prosecutor were legitimate observations. Indeed, at the end of the First World War, several groups, including foreign intelligence services, ambitiously embarked on a quest to find documents in order to accuse and try the Union and Progress Government. As mentioned by a British intelligence officer, this state of affairs had created “a very large market” of salable documents and had resulted in the “regular production of forgeries for the purposes of sale.”[5]

Ultimately, the documents were not in any way verified by the Court.

It could be concluded from these examples that Aram Andonian did not always tell the truth. Therefore, it would be fitting for serious historians to approach Andonian’s words with suspicion and caution. The direct acceptance of Andonian’s allegations without making any verification is problematic in terms of historical methodology. However, as it can be seen, Akçam, in his book, accepts the claims of the Naim-Andonian narrative without any questions and forms his arguments based on a set of assumptions.

According to Akçam, Orel and Yuca are also wrong in claiming that the cipher telegrams published by Andonian did not match with the ciphering technique and number groups used by the Ottoman Ministry of the Interior, and that therefore these telegrams should be false. Additionally, Akçam asserts that the objections by Orel and Yuca about the type of paper used in Andonian’s documents are completely groundless. Giving several examples about these objections, Akçam concludes that the ciphered telegrams published by Andonian are “congruent with the cipher telegrams in the Ottoman Archive and that there is no discrepancy among them, and that therefore these could be original documents.”

Following these examples, Akçam claims that several incidents and persons mentioned in the memoirs of the so-called Naim Efendi and in documents published by Andonian can be also encountered in Ottoman archival documents, and thus concludes that these documents are authentic.

Akçam’s claims will be analyzed in detail below. However, there is an important issue that must mentioned before reviewing Akçam’s book. Throughout his book, when presenting and summarizing the findings of Orel and Yuca in their studies about Andonian’s documents, Akçam distorts these findings, and attributes to Orel and Yuca false assertions that were never made by them. Then, he attempts to refute these assertions that he claims were made by Orel and Yuca, and based on this, he concludes that the study by Orel and Yuca are unreliable and full of mistakes. With such manipulations, he asserts that claims about the forged nature of Andonian’s documents are claims that can be “easily refuted”.

Although it is possible that readers who have no prior knowledge on the issue and who learn about the claims put forth on the forged nature of these documents only from erroneous representations by Akçam might be impressed by Akçam’s allegations, those who personally read Orel’s and Akçam’s work will see that many of Akçam’s assertions are invalid. Analyzing these subjects, this article aims to provide readers with a more balance perspective.

THE EXISTENCE OF NAIM BEY

Akçam, at the very beginning of his book, refers to arguments about whether the documents published by Aram Andonian are authentic and whether Naim Bey who is claimed to have provided these documents to Andonian was a real person. According to Akçam, the claims by Şinasi Oral and Süreyya Yuca may be summarized as follows:

The authors [Orel and Yuca] base their claims on three important arguments: 1) there was no Ottoman official by the name of Naim Efendi, 2) There cannot be a memoir by non-existent person, thus, there are no such memoirs, 3) The documents claimed to belong to Talat Pasha are distorted, fake documents.[6]

The obvious problem here is the presentation of the arguments of Orel and Yuca in an extremely inaccurate and shallow manner. First of all, Oral and Yuca do not in any way bring forward a claim that “there was no Ottoman official by the name of Naim Efendi.” According to Orel and Yuca, there might be different possibilities on this subject, but that, given the limited knowledge at hand, it is not possible to arrive at a definitive judgement. In the relevant chapter of their book, Orel and Yuca discuss the matter in the following way:

…it can be said that there are three possibilities regarding Naim Bey:

a) Naim Bey is a fictitious person.

b) Naim Bey is an assumed name.

c) Naim Bey is an actual person.

In these circumstances, it seems impossible to make a definite judgement on whether Naim Bey was an actual person or not. The only point which can be made with certainty is that if Naim Bey actually existed, he was undoubtedly an unimportant official. Indeed, Andonian confirms this in his letter of 26 July 1937, where he writes: ‘Naim Bey was an entirely insignificant official…’[7] [underlines have been added]

As it can be seen above, Oral and Yuca clearly state that in the light of all this information, it is not possible to arrive at a definitive judgement on the subject. However, if an official by the name of Naim Bey indeed existed, they reach the conviction that he was a low ranking official who would not have had access to these secret documents.

After distorting the arguments of Orel and Yuca, Akçam then proceeds to invalidate the claims he attributed to them. By referring to three different documents (which he presents as “Ottoman Documents”) that mention an official by the name of Naim Bey, Akçam tries to arrive at the conclusion that one of the basic arguments of Oral and Yuca is incorrect.

It is quite problematic to present these three documents as “Ottoman Documents”, since one of these documents is among the documents published by Aram Andonian -the authenticity of which is under doubt. The other two documents referenced by Akçam are two pieces of Naim-Andonian documents that are part of the Andonian Collection contained in the Nubarian Library of Paris. These are not Ottoman archival documents. It is quite apparent from the facsimiles of these documents that Akçam provides in page 52 of his book, that the signature which allegedly belongs to the Governor (Tr. Vali) of Aleppo Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey is the exact same as the fake signature attributed to Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey in the documents published by Andonian. Since signature issue will be further elaborated below, it will be sufficient to briefly mention at this point. The said fake signatures are quite different from the authentic signature of Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey contained in the Ottoman archival documents. Thus, Akçam makes use of one batch of Naim-Andonian documents for substantiating another batch of Naim-Andonian documents, and presents these documents as "Ottoman Documents”.

Another source employed by Akçam to prove that Naim Bey was a real person is a document -in volume 7 of the collection published by the ATASE Department of the General Staff (Tr. Genel Kurmay ATASE Dairesi Başkanlığı) in the year 2007 under the title of Armenian Activities According to Archive Documents (Tr. Arşiv Belgeleriyle Ermeni Faaliyetleri)- that makes reference to an official by the name of Naim Efendi. In the document collection in question, it can be seen that the testimony of a former dispatch officer named Naim Effendi was taken for the corruption that was taking place in the region and that he was made to sign his testimony.

In the document in question, the official named Naim Effendi is described as follows: “This is the testimony of Naim Efendi, son of Hüseyin Nuri, married, 26 years old, from Silifke, Former Meskene [Maskanah] Dispatch Officer, currently municipal grain warehouse officer [Tr. hububat ambar memuru]. (14-15 November 1916). [8]

Aram Andonian mentions in his book that the individual whom he introduces as Naim Bey could have been present at Meskene. For this reason, there is the possibility that the Naim Efendi in the document that has been published by ATESE could be this person. However, as Orel and Yuca touch upon, serious question marks exist as to how an individual who was a civil servant in a small district (Tr. kaza) like Meskene and who had been dismissed shortly after from his duty could have gotten his hands on written top secret communications between the Minister of the Interior and the Governor.[9]

According to Akçam, Naim Efendi served as the head clerk of the Aleppo Dispatch Director General (Tr. Sevkiyat Genel Müdürü) Abdülahad Nuri Bey, and it was through this position that he might have obtained the documents. However, besides the narrative of Naim-Andonian, there is no other evidence in our hand regarding Naim Efendi having served in this position. The only source about this is the sentence attributed Andonian to Naim Efendi: “I have been appointed to the head clerk position of Abdülhalad Nuri Bey”, allegedly uttered by Naim Efendi after he came to Aleppo. Apart from the narrative of Naim-Andonian, there has not yet been any findings to verify this sentence. The memoirs text published by Akçam also does not contain any statement or information in this direction.[10]

Serious problems arise even if we assume that the Naim-Adonian narrative is accurate, since according to the document published by ATESE, as of November 1916, the individual named Naim Efendi’s duty was that of a municipal grain warehouse officer. The explanation based on this assumption would have made sense to a certain extent if the documents published in the Naim Efendi collection covered events only before this date. However, the Naim-Andonian documents and the Naim Efendi Memoirs correspondences stretch until February 1917. The critical question about the individual named Naim Efendi is how, as a Municipal Grain Warehouse Officer, could he have obtained the alleged top secret communication between the Governor and the Minister of the Interior? This question becomes even more critical when one considers that Naim Efendi’s testimony on allegations of corruption was taken during the dates in question. Starting from November 1916, Naim Efendi served in a position in which, unequivocally, he could not have reached the said correspondences. Also, due to the allegations of corruption, he must be viewed as someone whose statements was quite difficult to be believed in. We must accept that, under normal circumstances, it would not be expected for such an official to have access to the said correspondences. However, Akçam, based on the narrative of Naim-Andonian and making assumption upon assumption without relying on any objective finding, accepts it as fact that Naim Efendi had access to these documents during aforementioned dates and that his memoirs are authentic.

As a result, first of all, Akçam wrongly presented here Orel and Yuca’s arguments and attributed claims to Orel and Yuca that were not put forth by them. Afterwards, by mentioning about the existence of an official named “Naim Efendi” in Ottoman archive documents, Akçam attempted to refute false claims never put forth by Orel and Yuca. In this way, by way of deception, Akçam arrived to the conclusion that the conclusions of Orel and Yuca are wrong. When the books of Orel and Yuca are examined, these allegations (which may affect readers who do not know the subject matter) are rather trivial and insignificant. In addition to these issues, Akçam, by accepting all the information given by Andonian about the official named Naim Efendi as being correct, assumes that the official named Naim Efendi was in a position that enabled him to reach all relevant information. Given the above-mentioned problems, it becomes apparent that these assumptions of Akçam are based on very weak premises.

CIPHERING TECHNIQUES

A significant part of Akçam's book is devoted to the ciphered telegrams used by the Ottoman Minister of the Interior. In their books, Orel and Yuca argued that the number groups used for ciphering in Naim-Andonian telegrams did not conform to the number groups used in the telegrams of the Ottoman Archives, and that these number groups were constantly changed at certain time intervals for security reasons. In the relevant part of his book Akçam, contrary to the claims of Orel and Yuca, claims that the ciphers formed with binary, ternary, quaternary, and quinary number groups were used at the same time and in a mixed way throughout the war. Akçam, for Orel and Yuca's claims, arrives at the conclusion that “these arguments are completely wrong and do not have any material basis”.[11]

On this subject, Akçam provides reference to a number of archive documents, and afterwards gives place in his book to facsimiles of some of these documents. Orel and Yuca claimed that in the documents they found in their research, the two, four, and five digit numbers were changeably used at different times during the war. In this respect, the telegrams using three digit numbers found by Akçam is new information.

As it is known, in the book of Aram Andonian, the documents he published and provided facsimiles for use two and three digit ciphers. Based on the existence of two and three digit numbers amongst the documents used by him, Akçam arrives at the conclusion that the documents published by Andonian and the Ottoman Archive documents are in full harmony and that there is no discrepancy between them.[12]

Despite this new piece of information provided by Akçam, there is an important issue that needs to be taken into consideration here. Documents utilized and the facsimiles of which have been published by Orel and Yuca are composed of telegrams sent from the center to the provinces (Tr. vilayetler). However, all documents referenced by Akçam in his book (he uses the facsimiles of some of them as well) were sent from the provinces and various commissions in the provinces to the center, thus to the Ministry of the Interior.[13] This situation will only gain clarity if all the numbers used in ciphered telegrams to the Aleppo Province from the Ministry of the Interior are analyzed in their entirety. Furthermore, as can be understood from the filing numbers in the archives, the telegrams sent from the provinces to the Center and used in Akçam's book had not yet been classified at the time of Orel and Yuca's work, and were documents that were classified and made available to the readers later on. That is to say, during in which Orel and Yuca conducted their research, they might not have had the opportunity to examine these documents. As such, this issue should not be overlooked when criticizing Orel and Yuca’s work.

Besides these, the only source of suspicion about the falsity of the ciphered telegrams contained in Naim-Andonian documents is not just the difference between the number groups used in the ciphered telegrams in the Ottoman archives and those used in Naim-Andonian telegrams. In Naim-Andonian documents, in a quite strange manner, “binary” and “ternary” number groups are used in the same document. For example, although the telegram dated 29 September 1915 attributed by Andonian to Minister of the Interior Talat Bey was written with cipher composed of three digit numbers, two digit numbers exist in the first, fourth, fifth, sixth, and seventh lines of the telegram.[14] Likewise, the telegram dated 26 December 1915 that is attributed to Abdülahad Nuri Bey ciphered with two digit numbers contains three digit numbers in the first, eleventh, fourteenth lines.[15] Similarly, the telegram dated 20 March 1916 attributed again to Talat Bey, although consisting of three digit numbers, contains two digit numbers in its sixth line.[16]

The usage of mixed number groups necessitates two separate cipher keys for the deciphering of a telegram. Yet, as Orel and Yuca underlines, the opening of such a document is not possible due to ciphering technique. In none of the authentic telegrams for which Akçam gives examples (he supplies the facsimiles of some of them) in his book based on the Ottoman Archive is there a similar case, meaning the mixed usage of different number groups in the same text. Akçam ignores this evident and striking difference between the authentic documents in the Ottoman Archive and the Naim-Andonian documents, argues that there is no contradiction and difference between them, and claims that Naim-Andonian documents could be authentic. Interestingly, there are simply no examples of number groups with different amount of digits being used within the same text in the Ottoman Archive documents the facsimiles of which were provided by none other than Akçam in his book. It is thus revealed that there is a serious difference between the Naim-Andonian Documents and the Ottoman Archive documents.

LINED PAPER ISSUE

According to Akçam, one of the assertions as to the falsity of Naim-Andonyan documents is “related to the papers that the documents were written on. Orel and Yuca presents the fact that one of the documents was written on a lined paper as the evidence of its falsity.”[17] According to Akçam, this is a quite nonsensical and bizarre situation:

Authors’ judgements like lined papers “cannot be expected to have been available in Ottoman state offices” and their utilization of this judgement as the proof of the falsity of a document is inapprehensible. In the period that we are dealing with, lined papers were used by the Ottoman bureaucracy.[18]

Following this, Akçam mentions that lined papers were used quite often in the Ottoman Archives and even gives quotations from some archive documents. After all these arguments, Akçam arrives at the following ostentatious conclusion:

As it can be seen, Orel and Yuca’s argument on the falsity of one document of Naim Bey for being written on lined paper is completely false. The rule in ciphered correspondence was not the use of plain paper, but the use of lined paper. The fact that the document that Naim Efendi gave is written on lined paper is not a proof for its falsity, on the contrary, it is a proof of its authenticity. What I would like to add as the final note to this section is that the twelve points that Orel and Yuca put forward to prove the falsity of Naim Efendi’s documents, most of which are the lined paper argument type, are arguments that are easy to disprove.[19]

However, Akçam here distorts another important objection of Orel and Yuca against the claimed authenticity of Naim-Andonian documents by again resorting to a trickery. In their books, Orel and Yuca in no way claim that “one telegram having been written on lined paper” is “the proof of its falsity”. As shall be demonstrated in more detail below, Orel and Yuca’s main objection is based on the fact that this document was written on a “double lined paper” that “bears no official inscription”.

Orel and Yuca raise no objection to the standardly used single lined papers. When the documents used in Orel and Yuca’s book (they also give place to these documents’ facsimiles) are examined, Akçam’s assertion turns out be absurd, placing Akçam in a comical position. This is so because, it is clearly apparent that the ciphered telegrams that Orel and Yuca took from the archive (and produced exact photos of) are written on single lined papers.

In line with this, telegrams dated 26 August 1915 and 11 December 1915 that were sent by the Minister of the Interior Talat to certain lieutenant governorships (Tr. mutasarrıflık) that were published by Orel and Yuca in their books should be viewed:

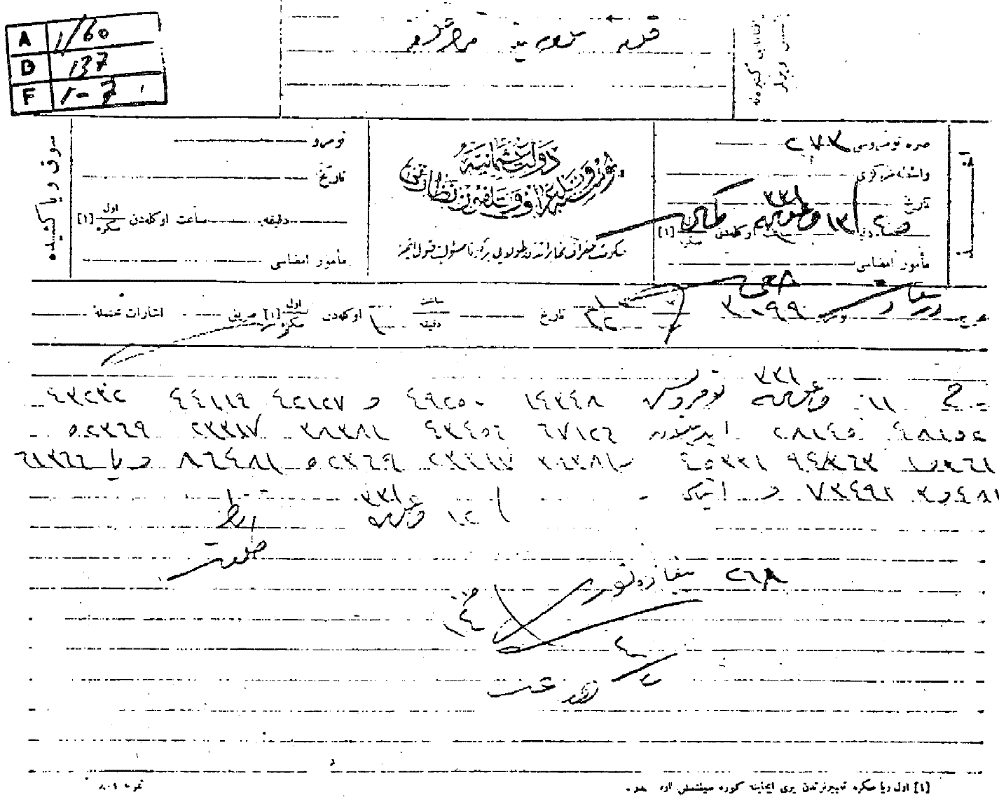

Document 1

The copy of the ciphered telegram which was written on official “single lined” paper dated 26 August 1915 that was published by Şinasi Orel and Süreyya Yuca in page 77 in their book. This telegram was sent by Minister of the Interior Talat Bey to Lieutenant Governorship of Çanakkale.

Document 2

The copy of the ciphered telegram which was written on official “single lined” paper dated 11 December 1915 that was published by Şinasi Orel and Süreyya Yuca in page 78 in their book. This telegram was sent by Minister of the Interior Talat Bey to Lieutenant Governorship of Karahisar-ı Sahip (Afyon).

.png)

As it can be seen in authentic telegrams that are replicated above, Orel and Yuca themselves published documents containing telegrams that were written on single lined papers. The objection of Orel and Yuca on this issue is not about the papers being single lined. The objection of Orel and Yuca is as follows:

Among the “documents”, the one numbered 76 was written on double lined paper that contains no official sign. It cannot be expected that a paper that rather looks like the papers used in writing (calligraphy) classes in French schools to be present in Ottoman bureaus as official papers.[20]

First of all, the objection of the authors is to the fact that the paper is “double lined”, and more importantly, to the paper’s “lack of any official sign” in contrast to Ottoman Archive documents. Akçam completely ignores the objection to the paper published within Naim-Andonian documents due to its lack of any official sign and makes no comment on this point. In addition, by distorting Orel and Yuca’s objection to “double lined paper”, Akçam argues that they, instead, claimed that “lined paper” was not used by the Ottoman bureaucracy. Only by distorting the arguments of Orel and Yuca is Akçam able to arrive at the conclusion that their arguments are “inapprehensible” and “completely false.” Not only that, Akçam further states that Orel and Yuca’s arguments as to the falsity of the documents are all lies and wrong, and that they can be easily disproved.

However, as can be seen in the copies of the telegrams presented above, Orel and Yuca do not object to the single lined papers, and even published documents written on single lined papers. Akçam here again first distorts Orel and Yuca’s arguments, then attempts to disprove the false arguments that were not advanced by Orel and Yuca. Within such confusion, Akçam overlooks and tries to hide away Orel and Yuca’s objections about the papers being “double lined” and about the absence of official inscriptions on these papers unlike authentic Ottoman Archive documents.

TELEGRAM NUMBERS

In the work that they published in 1983, Orel and Yuca drew attention to the fact that the telegrams amongst the Naim-Andonian documents are different from the Ottoman Archive documents in terms of filing numbers as well. According to Orel and Yuca, there is absolutely no connection between the filing numbers used for the Naim-Andonian documents and the filing numbers of the authentic telegrams (contained in the Ottoman Archive) that were sent in the same date, and the filing numbers that are used in the Naim-Andonian documents contain great discrepancies. Furthermore, no record exists for the Naim-Andonian documents in the incoming-outgoing documents log of the Aleppo Province. Amongst the telegrams that are present in the Ottoman Archive, even though from time to time one comes across telegrams that were sent during the same time as the Naim-Andonian telegrams, it is seen that (both in terms of the telegram filing numbers and their contents) these two sets of telegrams are completely different from one another.

According to Akçam, Orel and Yuca are wrong with their assertions on this subject. According to Akçam, Ottoman Minister of the Interior had had installed a telegram machine in his own house, and from time to time communicated with governors through it and sent telegrams to provinces from his house. Again, according to Akçam, it is impossible to know what kind of filing numbering was used in these telegrams that were sent from the house of the Minister of the Interior.[21] Therefore, according to Akçam, the incongruence exhibited by the Naim-Andonian documents’ filing numbers with that of the archive documents is not a proof for the Naim-Andonian documents being forgeries.

First of all, again showing no evidence, Akçam makes the assumption that all Naim-Andonian documents were sent from the house of Minister of the Interior Talat Bey. Both in the explanations made by Andonian about the documents, and in the text of the “memoirs” that Andonian alleges belong to the Naim Efendi, there is simply no indication that the telegrams were sent from the Minister of the Interior’s house. On the contrary, it is clearly indicated that these documents were sent from the Ministry of the Interior. Additionally, it is clearly (without leaving room for doubt) indicated in the Naim-Andonian documents that the telegrams from Aleppo to the center were sent to the Office of the Ministry of the Interior (Tr. Dâhiliye Nezareti Celilesine), and they give no space to personal remarks such as “Addressed to Minister of the Interior Talat Bey” (Tr. Dâhiliye Nazırı Talat Beyefendi’ye).

In such circumstances, the argument about the aforementioned correspondences having been carried out from Talat Bey’s house comes across as being a contrived interpretation.

Additionally, the inconsistency regarding the filing numbers given to the telegrams are not solely present for the ones alleged to have been sent from the Ministry of the Interior to the Aleppo Province. The same inconsistency is also present in the telegrams alleged to have been sent from Aleppo to the center, meaning the Ministry of the Interior. Contained amongst the Naim-Andonian documents, the telegram attributed to Adbülahad Nuri Bey numbered 76 and dated 7 March 1332 (20 March 1916) is the most striking example. According to the Rumi Calendar used by the administrative system of the Ottoman State, the new year starts at 1 March 1332 (14 March 1916). According to this, for the telegram attributed to Adbülahad Nuri Bey to be numbered 76, he would have had to send 76 ciphered telegrams to İstanbul between the dates 1-7 March 1332 (14-20 March 1916), meaning in just seven days.[22] In this respect, the inconsistency about the numbering in the Naim-Andonian telegrams is revealed to be present for both the telegrams sent from Ministry of the Interior to Aleppo, and the ones sent from Aleppo to the center. In the section of his book touching upon this subject, Akçam has overlooked this as well and does not provide any explanation.

SIMILARITY WITH OTTOMAN DOCUMENTS

An important section of Akçam’s book has also been allocated to his efforts to prove the presence of similarities between the memoirs alleged to have belonged to Naim Efendi and the Ottoman Archive documents. In this respect, the author gives ten different examples in order to showcase the argument that there are great similarities between what is being told in the memoirs of Naim Efendi and the events that transpired according to the Ottoman Archive documents. For this reason, the author arrives at the conclusion that the Memoirs and the Documents must be true. It is not possible to reach a judgment on the veracity of Akçam’s arguments without examining one by one the documents Akçam gives as examples. However, even if we were to accept that all his allegations are true, the similarity between the Ottoman Archive documents and the Naim-Andonian materials is not a proof for the authenticity of these documents. If the person producing the forged documents is above a certain level of intelligence, that person will anyhow attempt to make the documents and the memoirs resemble real events.

Hence, concerning another forged document prepared for the Armenian Question and generally known as the “Ten Commandments”, Canadian historian Gwynne Dyer has likened it to a document construction effort that would be congruent with events that had already transpired.[23]

In a similar way, as drawn attention to by Dutch historian Erik Jan Zürcher as well, it should come as no surprise that the contents of forged document resemble and coheres with actual events. According to Zürcher, if some members of the bureaucracy are to produce forged documents in order to earn money, they would put the effort to make the contents of forged documents resemble actual events as much as possible.[24]

Examples similar to this are not confined to the Armenian Question. To give the impression of being authentic, it is not unusual for forged documents produced for various topics to contain a certain amount of true information about actual events and people. The most striking example for this is the so-called “Hitler Diaries” that created quite a sensation in the 1980s. In the diaries, Hitler’s various speeches, notes, and meetings are contained in a way that is similar to the actual ones. Moreover, the said forged diaries give place to texts of certain works or newspaper pieces about Hitler exactly as they appeared in those works and pieces. This was enough to mislead some historians; taking into account all the similarities, the details, and the variety of the materials, some historians such as Hugh Trevor-Roper and Gerhard Weinberg in the beginning expressed the view that these diaries were authentic. However, at the end of the examination conducted by German forensic experts, it was revealed that the “Hitler Diaries” were fake and that certain ingredients of the diaries such as the papers, bindings, adhesives etc. were not yet in use during the period when Hitler lived.[25]

If the verification logic employed by Akçam for the Naim-Andonian documents were to be applied to the “Hitler Diaries”, it would result in the bizarre and erroneous conclusion that the fake diaries are real. This is so because, under Akçam’s logic, the text contained in the diaries being verified by the exact same texts in other sources would point to the authenticity of the diaries. As indicated above however, as a result of the examination of German forensic experts, it has been revealed -leaving no room for doubt- that the diaries are fake. It is therefore clearly revealed that forged documents relaying information close to the truth about topics concerning some actual events, speeches etc. does not directly mean that such documents are authentic.

What is essentially needed, concerning the dispute of whether or not the documents are authentic, is not explaining the similarities, but explaining the inconsistencies. In the dispute over the Hitler diaries, historians, while drawing attention to the similarities they have with actual speeches and some sources written about Hitler, come to the conclusion that the diaries are fake by pointing to a series of contradictions and rather absurd errors within the diaries.[26] Akçam’s work is essentially quite weak on this point. Below, a more balanced picture will be drawn for the readers by examining the points ignored by Akçam.

THE POINTS IGNORED BY AKÇAM

Akçam remains completely silent on subjects for which no explanation can be given: the chronological discrepancies of the Naim-Andonian documents, the signature attributed to the Governor of Aleppo being different from the actual one that is contained in the Ottoman Archive, Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey’s signing of some documents with the title “Governor” before he had actually been appointed as a governor, and also both Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey’in and Abdülahad Nuri Bey adding notes to the documents and signing them during dates when they were still in İstanbul and had not yet reached Aleppo. A similar situation is present for the letters attributed to Bahaettin Şakir Bey, which were allegedly sent from İstanbul to Adana in February and March 1915, despite the fact that in the said dates he was not in İstanbul but in Erzurum. Additionally, while the Ottoman Archive documents used by Akçam as examples are all written on papers bearing official inscriptions, the papers on which Naim-Andonian documents are written do not, which has been completely ignored by Akçam.

It must be underlined that the signatures attributed to the Governor of Aleppo Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey occupy a special place in the dispute over whether or not the documents are authentic. This subject will be touched upon in more detail below. Before moving forward to this subject however, it must be indicated that there are errors and inconsistencies in the Naim-Andonian document that are ignored and never mentioned by Akçam.

All the telegrams belonging to the Ottoman Archive used by Akçam as reference (he provides facsimiles for some of these telegrams) have been written on letterheads bearing official inscriptions.[27] However, the telegrams and documents in the Naim-Andonian documents are different in this respect. Some of them have been written on blank papers bearing no official inscription whatsoever and which are different from the ones used by the Ottoman bureaucracy. Akçam makes no comment on and remains silent about this blatant inconsistency between the papers on which the Ottoman Archive documents and the papers on which the Naim-Andonian documents are written.

Again, in Akçam’s book, the cipher number groups used in all the ciphered telegram texts are constituted of the same amount of digits. For example, in a telegram using four digit ciphers, all number groups are four digits and number groups with different amount of digits are not used in the text. The same is true for telegrams using two, three, and five digit numbers, and number groups with different amount of digits were not confused with each other within the telegrams.

As previously indicated, however, in the telegrams of the Naim-Andonian Documents, both two digit and three digit numbers are used in a mixed manner within the same telegram texts. As explained above, this is quite ill-advised in terms of ciphering techniques because it will require two different cipher keys for the telegrams to be solved and create great complications and pointlessness.[28] This clear inconsistency between the Ottoman Archive documents and the Naim-Andonian documents is yet again ignored by Akçam throughout his book and this problem is thus evaded with silence.

The inconsistencies in the Naim-Andonian documents are not limited to this. In the said documents, a telegram is sent on 3 September 1331 (16 September 1915) by Minister of the Interior Talat Bey to the Governor of Aleppo, and on 5 September 1331 (18 September 1915) Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey writes some notes on the telegram paper and puts his signature underneath it as the Governor.[29] Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey addresses Abdülahad Nuri Bey as he writes the said notes. However, in the dates during which those telegrams were sent, the notes were written, and the signature was put, the Governor of Aleppo was Bekir Sami Bey, not “Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey”.[30] Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey was only appointed as the Governor of Aleppo by 10 October 1915. This means that if the documents were actually authentic, it should have been Bekir Sami Bey, and not Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey, who signed the telegram sent on 16 September 1915. Also, despite the note dated 18 September 1915 having been written to address Abdülahad Nuri Bey, Abdülahad Nuri Bey had not yet been appointed to his position in Aleppo by that date. According to the Ottoman Archive records, in a telegram he sent on 14 October 1915, Minister of the Interior Talat Bey mentions to Director of Settlement for Tribes and Migrants (Tr. İskân-ı Aşairin ve Muhacirin Müdürü) Şükrü Bey about Abdülahad Nuri Bey being considered for appointment to Aleppo and asks Şükrü Bey about his thoughts on Abdülahad Nuri Bey.[31] In other words, as of the date of 14 October 1915, Abdülahad Nuri Bey had not yet been appointed to his position in Aleppo, and the decision process about him had been still ongoing, and other bureaucrats had been asked about their opinions on him.

Thus, in this so-called document, there is a correspondence between a governor and a civil servant, both of whom had not yet been appointed to their posts. This chronological inconsistency regarding the posts and the terms of office of these individuals is one of the serious evidences that prove these documents being fake. However, Akçam never touches upon this issue and in fact remains silent with regard to these inconsistencies throughout his book.

As indicated above, Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey was only appointed as Governor to Aleppo by 10 October 1915. Therefore, it can be argued that the signatures attributed to Governor of Aleppo Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey in the Naim-Andonian documents after 10 October 1915 (27 September 1331) are rather less suspicious. There is another document in Naim-Andonian documents sent from the Ministry of the Interior in 29 September 1331 (12 October 1915). Similarly, four days after this telegram on 3 October (Teşrin-i Evvel) 1331 (16 October 1915), Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey seemingly noted down his name as Governor of Aleppo and signed the document.[32] Therefore, since Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey was appointed as Governor six days before this telegram, this document seems comparably less suspicious.

On the other hand, when one looks at the Ottoman Archive registries, although Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey was appointed as Governor on 10 October 1915, it can be seen that he was in İstanbul until 1 November 1915, and that he only arrived to Aleppo on 8 November 1915. The same applies to Abdülahad Nuri Bey as well. Newly appointed Governor of Aleppo Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey and Abdülahad Nuri Bey left İstanbul together for Aleppo on Monday, 1 November.[33] A telegram stating that the two officials would arrive to Aleppo on 8 November was sent to İstanbul.[34] Thus, it is impossible for Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey and Abdülahad Nuri Bey to have written down notes or to have signed documents in Aleppo as of September and October 1915. This is so because they had arrived to Aleppo only by 8 November. This is another serious evidence that the documents are fake.

One part of Akçam’s book is also dedicated to Naim Bey’s place and term in office. In this chapter, Akçam touches upon the Ottoman documents that we present above on when Governor of Aleppo Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey and Abdülahad Nuri Bey were going to leave for Aleppo. These documents clearly prove that Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey and Abdülahad Nuri Bey were not in Aleppo and did not assume their posts before 7 November 1915. Based on this information highlighting the fact that the Naim-Andonian documents are fake, Akçam again remains silent and completely ignores the inconsistency between the Ottoman Archive Documents and the Naim-Andondan Documents.

The same inconsistency can be found in a letter attributed to Bahaettin Şakir Bey and which was supposedly sent by the Union and Progress Central Committee (Tr. İttihat-Terakki Merkez Komitesi) to the party’s Adana delegate Cemal Bey on 2 March 1915.[35] On the date in which the letter was sent, Bahaettin Şakir Bey was not in İstanbul but in Erzurum, and remained in Erzurum until 13 March 1915.[36] Thus, this is another indication that the Naim-Andonian documents are fake.

ON WHAT BASIS DID ARAM ANDONIAN ARGUE FOR THE AUTHENTICITY OF THE DOCUMENTS?

Andonian based his claim about the authenticity of the documents that he claimed were given to him by Naim Bey on the signature of Governor of Aleppo Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey. According to Andonian, after Naim Bey gave the documents to him, the documents were analyzed for their authenticity. Andonian stated that the signatures on the documents attributed to Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey were compared with Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey’s signature documents that belonged to him, and it was concluded that the signatures belonged to the Governor:

There is no doubt that these documents were taken out of the files of the Assistant Directorship of the Deportation Office in Aleppo. The Governor of Aleppo, after having had the orders he received from the Minister of the Interior (Talât Pasha) concerning the Armenians deciphered, appended a note with his signature to them in which he referred them for implementation to the Assistant Directorship of the Deportation Office where Naim Bey was a secretary.

When Naim Bey agreed to provide us with these documents, the Aleppo Armenian National Union, which was an official organization, had the handwriting and signatures (appended to the documents in question), examined. This examination lasted exactly one week. Other documents to which the Governor Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey had appended notes and his signature were examined, and even the smallest details were subjected to comparison. Finally, it was determined without any possibility of doubt that the handwriting and signature in the notes added to the documents belonged to the Governor Mustafa Abdülahlik Bey. This erased even the slightest suspicion as to the authenticity of the documents…[37]

As it can be clearly seen from this excerpt from a letter by Andonian, the main basis for the authenticity of the documents in question is the assumption that the signature on the documents attributed to Mustafa Abdukhalik Bey is genuine. However, a comparison of the genuine signatures that can be found in two letters from the Ottoman Archive that belong to Governor of Aleppo Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey with those in the Naim-Andonian documents reveal that the two groups of signatures are completely different. The said signatures are compared in the below chart.

.png)

Table 1 – Two sample signatures that are attributed to Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey in the Naim-Andonian Documents and two original signatures from the letters in the Ottoman Archives

In Table 1, sample number 1 and 2 are the signatures from Naim-Andonian documents attributed to Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey. Throughout the book, all the signatures attributed to Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey are exactly the same as these two fake signatures. However, taking into account Mustafa Abdulhalik Bey’s genuine signatures in sample number 3 and 4 that are taken from two letters dated 21 December 1915 and 7 February 1916 in the Ottoman Archive, it will clearly be seen that the signatures in the Naim-Andonian documents are undoubtedly fake. Therefore, it is revealed that Andonian’s most basic claim to prove the documents are authentic is in fact baseless and that the documents are indeed fake. Akçam again brushes aside this issue and provides no explanation for it.

CONCLUSION

As the detailed analysis given above shows, Akçam’s arguments on Naim-Andonian documents are based on the oversimplification and furthermore distortion of Orel and Yuca’s previous findings. In order to bring credibility to his claims, Akçam presents Orel and Yuca’s findings in a distorted manner and ignores these writers’ most basic objections. Akçam, who then answers the objections presented in an oversimplified and distorted manner, attempts to prove the authenticity of the Naim-Andonian documents by resorting to various manipulations. However, as has already been showed, while listing his allegations, he bases his arguments on serious logical errors and obvious distortions. Apart from these, in his book, Akçam remains completely silent on issues for which no explanation can be given, such as: the chronological discrepancies in the Naim-Andonian documents, the signature attributed to Governor of Aleppo being different from the genuine signature of the Governor contained in the Ottoman Archive, Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey’s signing of some documents with the title “Governor” before he had actually been appointed as a governor, and also both Mustafa Abdülhalik Bey’in and Abdülahad Nuri Bey adding notes to the documents and signing them during dates when they were still in İstanbul and had not yet reached Aleppo. Unable to present credible evidence to explain the inconsistencies and discrepancies of the Naim-Andonian documents, Akçam begins from various assumptions that he most of the time does not provide any evidence for to prove that the documents are authentic.

On top of this, Akçam does not present convincing explanations for the most basic objections (fake signatures, the type of paper used by the Ottoman bureaucracy, chronological discrepancies etc.) directed by Orel and Yuca towards the Naim-Andonian documents and ignores many of these objections. For these reasons, it becomes apparent that Akçam’s book cannot be treated as a credible source in the discussion concerning the authenticity of the Naim-Andonian documents.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Akçam, Taner. Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları, Krikor Gergeryan Arşivi. İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2016.

Andonian, Aram. Documents Officiels Concernant les Massacres Armeniens. Paris: Impremerie H. Turabian, 1920.

Andonian, Aram. Memoirs of Naim Bey. London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1920.

BOA DH DŞR 56-385. Telegram dated 13 October 1915 sent from Directorate of Public Safety (Tr. Emniyet-i Umumiye Müdüriyeti) to Şükrü Bey.

BOA DH ŞFR 496/53. Telegram dated 8 November 1915 from the Director of Public Safety (Tr. Emniyet-i Umumiye Müdürü) İsmail Bey to the Ministry of the Interior.

DH ŞFR 57/191. Telegram dated 31 October 1915 sent from the Directorate of Public Safety to Şükrü Bey.

Dyer, Gwynne. “Correspondence”. Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 9, 1973.

Harris, Robert. Selling Hitler: The Story of Hitler Diaries. London: Arrow Books, 2010.

Henke, Josef. “Revealing the Forged Hitler Diaries”. Archivaria, Volume 19, 1984.

Lewy, Guenter. The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey: A Disputed Genocide. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2007.

Orel, Şinasi and Süreyya Yuca. The Talât Pasha Telegrams – Historical fact or Armenian fiction? Lefkoşa (Nicosia): K. Rustem and Bro., 1983.

Orel, Şinasi ve Süreyya Yuca. Ermenilerce Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1983.

Sabis, Ali İhsan. Harp Hatıralarım: Birinci Cihan Harbi, Cilt II. İstanbul: Nehir Yayınları, 1990.

T.C. Genelkurmay Başkanlığı. Arşiv Belgelerinde Ermeni Faaliyetleri, Cilt VII. Genelkurmay Askeri Tarih ve Stratejik Etüt (ATASE) Başkanlığı Yayınları. Ankara: Genelkurmay Basımevi, 2008.

Zürcher, Erik Jan. “Ottoman Labour Battalions in World War I”. Hans-Lukas Kieser (ed.), The Armenian Genocide and the Shoah. Zürich: 2002.

[1] Şinasi Orel ve Süreyya Yuca, Ermenilerce Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü, (Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu, 1983), p. 7.

[2] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 8.

[3] Guenter Lewy, The Armenian Massacres in Ottoman Turkey: A Disputed Genocide (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2007) ; Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 18

[4] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 19.

[5] Lewy, A Disputed Genocide, p. 49.

[6] Taner Akçam, Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları, Krikor Gergeryan Arşivi (İstanbul: İletişim Yayınları, 2016), p. 8.

[7] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 23-24.

[8] T.C. Genelkurmay Başkanlığı, Arşiv Belgelerinde Ermeni Faaliyetleri, Cilt VII, Genelkurmay Askeri Tarih ve Stratejik Etüt (ATASE) Başkanlığı Yayınları (Ankara: Genelkurmay Basımevi, 2008), p. 94.

[9] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 11-12.

[10] For the text of the memoirs, please see: Akçam, Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları…, p. 154-223.

[11] Akçam, Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları…, p. 70.

[12] Akçam, Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları…, p. 97.

[13] Akçam, Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları…, p. 85-94.

[14] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 74-75.

[15] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 59.

[16] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 65-66.

[17] Akçam, Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları…, p. 94.

[18] Akçam, Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları…, p. 94.

[19] Akçam, Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları…, p. 94.

[20] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 60.

[21] Akçam, Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları…, p. 66-68.

[22] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 60.

[23] Gwynne Dyer, “Correspondence”, Middle Eastern Studies, Volume 9, 1973, p. 377.

[24] Erik Jan Zürcher, “Ottoman Labour Battalions in World War I”, Hans-Lukas Kieser (ed.), The Armenian Genocide and the Shoah (Zürich: 2002), p. 194 n. 1.

[25] Robert Harris, Selling Hitler: The Story of Hitler Diaries (London: Arrow Books, 2010).

[26] For an analysis of the content of the fake diaries, please see: Josef Henke, “Revealing the Forged Hitler Diaries”, Archivaria, Volume 19, 1984, p. 21-27.

[27] Akçam, Naim Efendinin Hatıratı ve Talat Paşa Telgrafları…

[28] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 59, 65-66, 74-75.

[29] Aram Andonian, Documents Officiels Concernant les Massacres Armeniens (Paris: Impremerie H. Turabian, 1920), p. 109.

[30] Orel ve Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 54.

[31] BOA DH DŞR 56-385. Telegram dated 13 October 1915 sent from Directorate of Public Safety (Tr. Emniyet-i Umumiye Müdüriyeti) to Şükrü Bey.

[32] Andonian, Documents Officiels, p. 110.

[33] DH ŞFR 57/191. In the telegram dated 31 October 1915 sent from the Directorate of Public Safety to Şükrü Bey, it is requested that “since Governor of Aleppo and Abdülahad Nuri Bey will set out for their journey on Monday, be present at Aleppo on their arrival.”

[34] BOA DH ŞFR 496/53. Telegram dated 8 November 1915 from the Director of Public Safety (Tr. Emniyet-i Umumiye Müdürü) İsmail Bey to the Ministry of the Interior.

[35] Andonian, Documents Officiels, p. 96-98 ; Aram Andonian, Memoirs of Naim Bey, (London: Hodder & Stoughton, 1920), p. 49-51.

[36] Ali İhsan Sabis, Harp Hatıralarım: Birinci Cihan Harbi, Cilt II (İstanbul: Nehir Yayınları, 1990), p. 378.

[37] Şinasi Orel and Süreyya Yuca, The Talât Pasha Telegrams – Historical fact or Armenian fiction? (Lefkoşa (Nicosia): K. Rustem and Bro., 1983), p. 13. The Turkish translation of this can be found at: Orel and Yuca, Talat Paşa’ya Atfedilen Telgrafların Gerçek Yüzü…, p. 13.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

AVIM HELD A BRAIN-STORM MEETING ON “EURASIAN PERSPECTIVES-TURKEY AND EURASIAN DEVELOPMENTS”

AVİM 19.02.2014 -

ARMENIA IS ON THE RIGHT TRACK

ARMENIA IS ON THE RIGHT TRACK

AVİM 14.05.2024 -

HATE SPEECH PUT INTO ACTION AGAINST TURKEY AND TURKS: FOUL-SMELLING PROVOCATION

HATE SPEECH PUT INTO ACTION AGAINST TURKEY AND TURKS: FOUL-SMELLING PROVOCATION

AVİM 31.01.2019 -

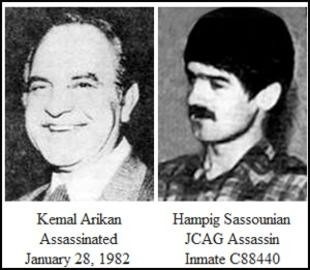

THE PAROLE OF HARRY (HAMPIG) M. SASSOUNIAN, THE PERPETRATOR OF THE MURDER OF TURKEY’S CONSUL GENERAL TO LOS ANGELES KEMAL ARIKAN IN 1982

THE PAROLE OF HARRY (HAMPIG) M. SASSOUNIAN, THE PERPETRATOR OF THE MURDER OF TURKEY’S CONSUL GENERAL TO LOS ANGELES KEMAL ARIKAN IN 1982

AVİM 21.12.2016 -

NEW ARTICLE ON THE DASHNAK ERZURUM CONGRESS OF JULY 1914

NEW ARTICLE ON THE DASHNAK ERZURUM CONGRESS OF JULY 1914

AVİM 09.12.2021

-

POPE FRANCIS IN AZERBAIJAN

POPE FRANCIS IN AZERBAIJAN

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 14.10.2016 -

EUROPE’S LIMITS AND ITS LIMITLESS SILENCE

EUROPE’S LIMITS AND ITS LIMITLESS SILENCE

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 05.08.2020 -

THE TURBULENT POLITICAL CLIMATE AND THE PROTESTS TAKING PLACE IN THE STREETS OF TBILISI OVER THE 31 OCTOBER PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS

THE TURBULENT POLITICAL CLIMATE AND THE PROTESTS TAKING PLACE IN THE STREETS OF TBILISI OVER THE 31 OCTOBER PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS

Ceyda ACİCBE 12.11.2020 -

CONSTRUCTIVE EURASIANISM: REVISITING DEFINITIONS

CONSTRUCTIVE EURASIANISM: REVISITING DEFINITIONS

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 08.01.2025 -

JOE BIDEN’S STATEMENT ON 1915 EVENTS: PURPOSEFUL POLITICAL ACTIONS MAY CAUSE UNANTICIPATED CONSEQUENCES, AN ANALYSIS FROM THE SOCIOLOGICAL VIEWPOINT

JOE BIDEN’S STATEMENT ON 1915 EVENTS: PURPOSEFUL POLITICAL ACTIONS MAY CAUSE UNANTICIPATED CONSEQUENCES, AN ANALYSIS FROM THE SOCIOLOGICAL VIEWPOINT

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 03.05.2021

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"