In a recent interview with Chris Hedges,[1] an American presbyterian minister and journalist, historian Eugene Rogan of Oxford University made several oversimplified and biased statements concerning the Ottoman Empire in the First World War and the 1915 Events.

According to Eugene Rogan, Sultan Abdulhamit II was nicknamed “the Red Sultan” or “the Bloody Sultan” because of “the blood on his hands in … Bulgaria.” And by Bulgaria, Rogan no doubt means the harsh suppression of the April 1876 uprising in Bulgaria which were subsequently dubbed as “the Bulgarian Horrors” in the British press.

Surely, it would be a justified and modest demand to expect an Oxford University professor to get his facts straight and to have an accurate grasp of an empire’s history on which he claims expertise. Unfortunately, Rogan’s grasp of chronology seems deficient. Abdülhamit II could not be nicknamed “the Red Sultan” or “the Bloody Sultan” because of the alleged “blood on his hands in Bulgaria” as he only acceded to throne and became the sultan on 31 August 1876, long after the April 1876 Rebellion in Bulgaria was put down and order restored.

Similarly misleading is Rogan’s statement that after the mobilization and general conscription was announced, “the Armenians flock to these conscription centers in the towns and cities where they lived” and allegedly they “did so in great numbers.” This is disputed even by the Armenian sources, which note the general unwillingness and displeasure of the Armenians to enlist in the military. In some regions such as Sasun and Zeytun, the Armenians resisted conscription altogether and even attacked and killed recruitment officers. In others, mass desertions took place before and after hostilities commenced.

Moreover, Rogan entirely glosses over the fact that following the general mobilization and well before the Ottomans joined the war, the Armenians deserted to the Russians en masse, especially in the province of Erzurum and the sanjak of Bayezid. They subsequently joined the Russian forces as auxiliary bands. They included prominent Ottoman Armenian figures such as Karekin Pastırmacıyan, the deputy of Erzurum in the Ottoman Assembly. It was these bands that invaded the Ottoman territory in the first weeks of the war in November and massacred the civilian population, causing massive loss of life and flight among the Muslim population of the region. Surely, these developments changed the Ottoman view of the dependability of the Armenian conscripts. Rogan mentions none of these, but alleges that the Armenians in the Ottoman Army started to desert only after the Sarıkamış battle and that only as a result of their mistreatment following this battle. As noted, the mass desertions of Armenian conscripts and Armenian resistance to conscription started well before the actual start of war and well before any possible mistreatment or discrimination against the Armenians had been an issue.

Rogan’s narrative of the Ottoman war similarly suffers from factual mistakes, oversimplification, and one-sidedness. He asserts that one of the first fronts of the Ottoman Empire to “erupt into direct warfare” was “the dreadful battle of Sarıkamış at the very end of December 1914.” Again, for a historian claiming expertise in the Ottoman Empire in the First World War, this is a serious mistake. There were three large battles, namely Köprüköy, Azap, and Tutak battles, on the Russian front alone, not to mention those in Basra in Iraq (with the British), Kotur, Saray, and Başkale on the Iranian border (with the Russians), all of which took place before the Battle of Sarıkamış.

Similarly, Rogan states the Ottoman Third Army was “the strongest” Ottoman field army. This is again a serious mistake, since the strongest Ottoman field armies were defending the Ottoman capital in Thrace, especially on the Gallipoli Peninsula. By comparison, the Ottoman Third Army had much fewer men and was poorly equipped, fed, and clothed due to its long and vulnerable supply lines. It was further weakened by the mass desertion of the Armenian conscripts since August 1914 and the periodic outbreaks of violence and sabotage launched by the Armenian armed bands operating in the region.

Rogan’s narrative of the Armenian events of 1915 is similarly lopsided and oversimplified. He mentions an alleged Ottoman decision to depopulate Eastern Anatolia in March and April 1915, “which could only be assumed” as “a policy of extermination.” Like his account of the early stages of the war, Rogan’s discussion of the relocation and resettlement of Armenians to Syria is based on assumptions rather than concrete facts. He mentions none of the orders and regulations by the Ottoman government to help and protect the Armenian convoys in this process. Likewise, he does not mention that when the Armenian convoys were attacked, the Ottoman government tried to prevent it by punishing those guilty of such attacks or those officials who neglected their duties and failed to protect the Armenians. More than 1600 people were put on trial in the year 1916 as the war was going on, when the Ottomans were under no outside pressure and the fortunes of war seemed to be in their favor.

528 of those put on trial had been members of the security forces (the military and police). These personnel included people with high ranks such as captains, lieutenants, first and second lieutenants, commanders of gendarme squads, and police superintendents. Among those prosecuted, there were 170 civil servants, which represented diverse public service officials, such as district governors, medical managers, tax collectors, prefects, mayors, district managers, clerks, dispatch officials, property managers, and land register officials. About 1000 of the defendants were either bandits or random civilians who took part in pillaging and attacking the Armenian convoys during the relocations.

In conclusion, it is AVİM’s considered view that the account Rogan presents in the interview is factually wrong and highly biased. Almost all the details he gives are one-sided, misleading, inaccurate, or oversimplified, which renders his account unreliable.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

FREEDOM OF EXPRESSION

CONCERNS OVER THE PATRIARCH ELECTION

CONCERNS OVER THE PATRIARCH ELECTION

COMMEMORATIVE STAMPS FOR GULBENKIAN

COMMEMORATIVE STAMPS FOR GULBENKIAN

RACISM AND BIGOTRY IN ACADEMIA: THE ELYSE SEMERDJIAN CASE

RACISM AND BIGOTRY IN ACADEMIA: THE ELYSE SEMERDJIAN CASE

AVIM’S CONFERENCE ENTITLED SECURITY AND STABILITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH CAUCASUS

AVIM’S CONFERENCE ENTITLED SECURITY AND STABILITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH CAUCASUS

POPE’S VISIT TO AZERBAIJAN: A TEST FOR UNIVERSAL FRATERNITY

POPE’S VISIT TO AZERBAIJAN: A TEST FOR UNIVERSAL FRATERNITY

WHY IS ARMENIA SITTING IN A NATO FORUM?

WHY IS ARMENIA SITTING IN A NATO FORUM?

DISTURBING PUBLICATION TREND AT PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

DISTURBING PUBLICATION TREND AT PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

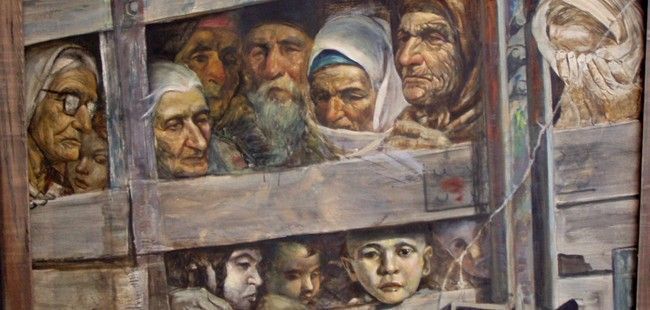

THE FORCED EXILES OF THE CRIMEAN TATARS AND THE CIRCASSIANS

THE FORCED EXILES OF THE CRIMEAN TATARS AND THE CIRCASSIANS

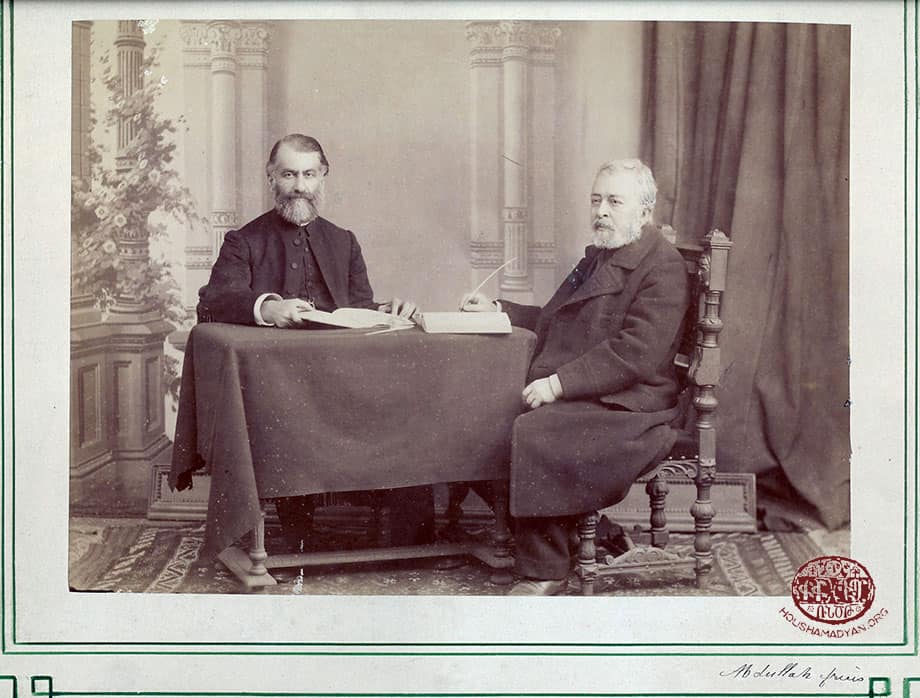

A PIONEER OF ARMENIAN CRITICAL HISTORIOGRAPHY: MADATIA KARAKASHIAN

A PIONEER OF ARMENIAN CRITICAL HISTORIOGRAPHY: MADATIA KARAKASHIAN