Introduction

To understand who the true culprits of the Rwandan genocide were, it is necessary to go back to the "Scramble for Africa" and briefly touch upon the history of the colonization of Africa by the seven Western European powers, namely Belgium, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Spain, and the United Kingdom.

Roughly speaking, the “Scramble for Africa” refers to the infamous invasion by the West European colonists between 1884 and 1914 of Africa and the dividing of the continent into different zones under the so-called names of protectorates, colonies, and free-trade areas.[1] To regulate colonialism, the first German chancellor Otto von Bismarck in 1884-1885 convened a conference in Berlin where the West European powers launched the “Scramble for Africa” and decided how to divide up the continent into different “spheres of interest.”[2] The Berlin Conference, which is also known as Congo Conference (German: Kongokonferenz) or West Africa Conference (Westafrika-Konferenz), is generally considered the “legal formalization” of the Scramble for Africa. Through this conference, borders in Africa were designed arbitrarily in West European capitals at a time when most of these colonial countries had barely settled in Africa and had little knowledge of local conditions. As a result, a significant portion of the populations belonging to the same ethnic groups in many African countries were divided between different states. Although arbitrary, these borders continued to exist after independence of African countries in the 1960s. These artificial borders dividing ethnic groups among newly formed states fed many ethnic struggles and conflicts. Ethnic division led to irredentism and nurtured secessionist movements. Hence, it can be said that West European colonialism set the stage for most of the deep sufferings of today's Africa by sowing the seeds of future conflicts through unbridled greed and selfishness.

In the framework of the African scramble, Germany settled mainly in three territories, called “protectorates”, in Africa. These were Togo and Cameroon in the west, German Southwest Africa (today’s Namibia), and German East Africa (today’s Tanzania, Rwanda, and Burundi) in the east. Rwanda was part of German East Africa from 1897 to 1918. Following the First World War, it became a Belgium trusteeship under a League of Nations mandate along with neighboring Burundi.

The Rwandan population is stated to consist of three groups of people: Hutu, Tutsi, and Twa. According to UN information papers, by 1994, Rwanda’s population stood at more than 7 million people comprising roughly 85% of Hutus, 14% of Tutsis, and 1% of Twas.[3] Leaving aside the racist discourses that point to genetic features and differences in physical attributes, the people of Rwanda are all considered to be of Bantu descent. A scholar asking a rationale question of “Who is a Hutu and who is a Tutsi?” states that “there cannot be a single answer that pins Hutu and Tutsi as transhistorical identities”, and argues the following:

“The clue to Hutu/Tutsi violence lies in two rather contemporary facts. The origin of the violence is connected to how Hutu and Tutsi were constructed as political identities by the colonial state, Hutu as indigenous and Tutsi as alien. The reason for continued violence between Hutu and Tutsi... is connected with the failure of Rwandan nationalism to transcend the colonial construction of Hutu and Tutsi as native and alien.”[4]

In fact, it is generally accepted view that during their colonial rule, Belgians favored the minority Tutsis over the Hutu and this intentional favoritism exacerbated the tendency of the minority group to oppress the majority creating a legacy of tension that exploded into violence even before Rwanda gained its independence. For instance, a Hutu revolution in 1959 forced as many as 330,000 Tutsis to flee the country, making them an even smaller minority. By early 1961, Hutus had forced Rwanda’s Tutsi monarch into exile and declared the country a republic. After a United Nations referendum held in the same year, Belgium officially granted independence to Rwanda in July 1962. However, ethnically motivated violence continued in the years following independence. In 1973, a military group installed Major General Juvenal Habyarimana, a moderate Hutu, in power. Habyarimana founded a new political party, the National Revolutionary Movement for Development (NRMD) and became the sole leader of Rwandan government for the next two decades. He was elected president under a new constitution ratified in 1978 and re-elected in 1983 and 1988. In 1990, forces of the Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF), consisting mostly of Tutsi refugees, tried to invade Rwanda from Uganda. Habyarimana accused Tutsi residents of being RPF accomplices and arrested hundreds of them. Between 1990 and 1993, government officials directed massacres of the Tutsi, killing hundreds. A ceasefire in these hostilities led to negotiations between the government and the RPF in 1992. In August 1993, Habyarimana signed an agreement at Arusha, Tanzania, calling for the creation of a transition government that would include the RPF. This power-sharing agreement angered Hutu extremists, who would soon take swift and horrible action to prevent it.

On 6 April 1994, a plane carrying Habyarimana and Burundi’s president Cyprien Ntaryamira was shot down over the capital city of Kigali, leaving no survivors. It has never been conclusively determined who the culprits were. Some have blamed Hutu extremists, while others blamed leaders of the RPF.

During the Rwandan genocide of 1994, members of the Hutu ethnic majority murdered as many as 800,000 people, mostly of the Tutsi minority. Started by Hutu nationalists in the capital of Kigali, the genocide spread throughout the country with shocking speed and brutality. By the time the Tutsi-led Rwandese Patriotic Front (RPF) gained control of the country through a military offensive in early July, hundreds of thousands of Rwandans were dead and 2 million refugees (mainly Hutus) fled Rwanda, exacerbating what had already become a full-blown humanitarian crisis.

Among the first victims of the genocide were the moderate Hutu Prime Minister Agathe Uwilingiyimana and 10 Belgian peacekeepers, killed on 7 April. This violence created a political vacuum, into which an interim government of extremist Hutu Power leaders from the military high command stepped on 9 April. The killing of the Belgium peacekeepers, meanwhile, provoked the withdrawal of Belgium troops and the UN directed that peacekeeper only defend themselves thereafter. Meanwhile, the RPF resumed fighting, and civil war raged alongside the genocide. By early July, RPF forces had gained control over most of country, including Kigali. As reports of the genocide spread, the UN Security Council (UNSC) voted in mid-May to supply a more robust force, including more than 5,000 troops. By the time that force arrived in full, however, the genocide had been over for months.[5]

Why is France accused of being accomplice in the Rwanda genocide?

As can be understood from the above explanations, France did not have a direct role as a colonial administration in Rwanda. However, since France has historically played a leading role in the colonization of Africa, she tried to be the dominant actor in the region in every sense in the 1990s. In the framework of this over ambitious agenda, France became involved in Rwanda in October 1990 under the guise of working towards the democratization of Rwanda in accordance with the guidelines drawn by the then President of France François Mitterrand at the Franco-African summit in La Baule (June 1990).[6] The French administration subsequently supported the conclusion of peace accords between the Rwandan government and the RPF. On 4 August 1993, the Peace Agreement between the Government of the Republic of Rwanda and the Rwandan Patriotic Front (the Arusha Peace Accords) was signed.

When the Rwandan President Juvénal Habyarimana and Burundian President Cyprien Ntaryamira were assassinated on 6 April 1994, the UN already had a peacekeeping force under Chapter VI of the UN Charter (the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda-UNAMIR) which was commanded by Canadian Lieutenant-General Roméo Dallaire in Kigali that had been tasked with observing the Arusha Accords provisions.[7] Following the start of the genocide and the murder of several kidnapped Belgian soldiers, Belgium withdrew its contribution to UNAMIR and UNIMIR was practically prevented from being involved in the protection of civilians.[8]

In the meantime, the French government made an announcement of its intentions to organize, establish, and maintain a "safe zone" in the south-west of Rwanda and started the infamous “Opération Turquoise” under the mandate of the UN Security Council Resolution 929 (1994).[9] The second operative paragraph of this resolution states the following:

“Welcomes also the offer by Member States (S/1994/734) to cooperate with the Secretary-General in order to achieve the objectives of the United Nations in Rwanda through the establishment of a temporary operation under national command and control aimed at contributing, in an impartial way, to the security and protection of displaced persons, refugees and civilians at risk in Rwanda, on the understanding that the costs of implementing the offer will be borne by the Member States concerned.” (Emphasis added)

France's efforts to manipulate domestic politics in Rwanda; its close ties with the ruling Hutu government; her arms sales to the country; her use of military force under the guise of defending the la francophonie (French-speaking world) and while doing so pushing aside the UN force; taking a stand with the Hutu forces in “Opération Turquoise” instead of being impartial as stipulated in the UNSC resolution caused France to be confronted with serious allegations that she was complicit with the Hutu in the Tutsi genocide in Rwanda. A recent example to these allegations is the memoirs (Rwanda, la fin du silence) penned by a French army veteran Guillaume Ancel who served in Rwanda during the genocide. According to press reports, Ancel asserted in the memoirs that “France portrayed its military operation as a humanitarian mission in order to hide its support of the genocidaires.”[10] It should also be noted that very recently published comprehensive report prepared by an US law firm upon the request of Rwandan government about the role of the French government in connection with the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda ends up with the conclusion that “the French government bears significant responsibility for enabling a foreseeable genocide.”[11]

The French research commission regarding the Rwandan Genocide

French President Emanuel Macron on 5 April 2019, by sending a letter to Prof. Vincent Duclert, a historian and Inspector General of French National Education, asked the establishment of a commission under his presidency to examine all the French archives concerning Rwanda, covering the years 1990-1994. Macron described the objectives of the Commission as the examination of all French archival collections concerning the pre-genocidal period and the genocide itself and drafting a report that would issue a historian’s critical understanding of the sources being examined. Additionally, he asked that the report would analyze France’s role and engagement in Rwanda during this period, considering the role of other actors who were also engaged during this period and contribute to a more in-depth knowledge of the causes and unfolding of the genocide against the Tutsi. He requested the completion of the report in two years.[12]

The report prepared by the Research Commission which can be cited as “the Duclert Report" was presented to President Macron on 26 March 2021 by letter of the president of the Commission, Professor Duclert. It is mentioned in the report that “The Commission doubtlessly missed certain documents, those that either disappeared or were never deposited in public archival centers.”[13] It is understood from the statements of Duclert in the interviews he gave after the publication of the report that the President of the French National Assembly did not grant access to the archives of the Parliament on this subject. Duclert states that for this reason, the archives of the Parliamentary Commission investigating the Tutsi genocide which conducted hearings with witnesses of the genocide in closed sessions could not be examined. In addition, it appears that the correspondence of the Speaker and Vice-President of the Assembly in the 1990-94 period could not be reached either.[14] It should be mentioned that the aforesaid French Parliamentary Committee was created in 1998 after pressures on France mounted for investigating the France’s responsibility in the Rwandan genocide. According to information provided in the aforementioned US law firm report, on 3 March 1998, Paul Quilès, then president of the National Assembly’s defense committee, issued a statement announcing the creation of a “fact-finding mission on Rwanda.” Quilè, a Socialist like Mitterrand, served as defense minister from 1985 to 1986, announced the mission’s goal to investigate France’s intervention in Rwanda between 1990 and 1994. However, he defined the scope of the mission in a restrictive way as only shedding light on the role that various foreign military forces may have played in the Rwandan crisis.[15]

The report submitted by the Research Commission to President Macron is a rather long report of 976 pages containing detailed explanations about the documents examined in the archives. As for the report’s findings, in our judgement, the main "finding" of the report regarding France's responsibility in the Rwanda genocide is included in the following paragraph of the Conclusions section of the report:

“Faced with such a tragedy, can we stop at just a historiographical observation? The Rwandan crisis ended in disaster for Rwanda and in defeat for France. Is France an accomplice to the genocide of the Tutsi? If by this we mean a willingness to join a genocidal operation, nothing in the archives that were examined demonstrates this. Nevertheless, for a long time, France was involved with a regime in Rwanda that encouraged racist massacres. It remained blind to the preparation of a genocide by the most radical elements of this regime. It adopted a binary view opposing on the one hand the ‘Hutu ally’ embodied by President Habyarimana, and on the other hand the enemy described as ‘Ugandan-Tutsi’ for the RPF. It was slow to break with Rwanda’s interim government that carried out the genocide and continued to place the RPF threat at the top of its agenda. France reacted belatedly with Operation Turquoise, which did save many lives, but not those of the vast majority of Rwandan Tutsi exterminated in the first weeks of the genocide. The research therefore establishes a set of responsibilities, both serious and overwhelming. These responsibilities are political insofar as the French authority demonstrated a continual blindness in their support for a racist, corrupt and violent regime, conceived originally as a model for a new French policy in Africa as introduced in the speech at La Baule.” (Emphasis added) [16]

The relevance of the main "finding" of the Research Commission report in terms of the provisions of the 1948 Genocide Convention

The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (the Genocide Convention) was signed in Paris on 9 December 1948, approved and proposed for signature and ratification or accession by UN General Assembly resolution 260 A (III) of 9 December 1948 and entered into force on 12 January 1951. France is among its original signatories and ratified the Convention on 14 Oct 1950.[17]

Article I of the Convention stipulates that “... genocide, whether committed in time of peace or in time of war, is a crime under international law...”. Article II states that “genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such: (a) Killing members of the group; (b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group; (c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; (d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; (e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Article III of the Convention specifies “the following acts as punishable: a) Genocide; (b) Conspiracy to commit genocide; (c) Direct and public incitement to commit genocide; (d) Attempt to commit genocide; (e) Complicity in genocide.” (Emphasis added)

As can be seen from these provisions of the Genocide Convention, the Convention foresees the punishment of not only those who directly perpetrated the genocide, but also the accomplices of the genocide.

Emmanuel Macron’s recent visit to Rwanda and his speech at the memorial of the Rwandan Genocide on 27 March 2021

French President Emmanuel Macron has recently paid a visit to Rwanda. French state-owned international news television network “France 24” described the event “as a symbolic visit” and stated that Macron, in a speech at the Kigali Genocide Memorial where the remains of 250,000 victims of the 1994 genocide are interred, recognized France's “responsibility” in the 1994 genocide but stopped short of an official apology. France 24 also referred in a separate paragraph to Macron’s following sentence in his speech: “France had not been complicit in the 1994 genocide.”

This short sentence, which seems to have been compressed into a part of Macron's speech describing the evil of genocide, is as follows:

“A genocide is not comparable. It has a genealogy. It has a history. It is unique. A genocide has a target. The killers had just one, criminal obsession: the eradication of the Tutsis, of all the Tutsis. Men, women, their parents, their children. That obsession swept away all those who tried to stand in its way, and it never lost sight of its goal. A genocide doesn’t happen overnight. It is prepared over time.... A genocide cannot be erased. Its marks are indelible. There is no end. There is no life after a genocide, one lives with it, as one can. In Rwanda, it is said that the birds do not sing on 7 April. Because they know. It is up to humankind to break the silence. And it is in the name of life that we must speak, name, and recognize. The killers who haunted the marshes, the hills and the churches did not bear France’s face. She was not an accomplice. (Original French text: Elle n’a pas été complice). The blood which flowed did not dishonour the weapons or hands of France’s soldiers, who themselves also saw the unspeakable, bandaged wounds, and suppressed their tears...”[18]

At this point, it is possible to say that the important point in Macron's symbolic visit to Rwanda was not whether France formally extended apology to Rwanda during the visit but was the official declaration made by the French President that France was not complicit in the Rwandan Tutsi genocide.

Conclusion

The 1990s constitute a "critical juncture" in world history. It was a period of significant change, which typically occurs in distinct ways in different countries. In this context, it should be remembered that notable political events and developments were concentrated in the 1990s. For example, we can cite the following events: The end of Cold War; the dissolution of Soviet Union and disbandment of Warsaw Pact; German unification; the First Gulf War; the breakup of Yugoslavia and emergence of seven new independent states following its dissolution; wars in Bosnia-Herzegovina and Kosovo; genocide in Srebrenica/Bosnia-Herzegovina, and finally the signing the Treaty of Maastricht which created today’s European Union.

In fact, the 1994 Genocide against the Tutsis in Rwanda is one of the most horrific chapters of this “critical juncture”. Almost all the above-mentioned events in this period have, in one way or another, reached a conclusion. The newly independent countries joined the international community. These countries are involved in various international structures in Europe. The perpetrators of the Srebrenica genocide have been tried and punished in international courts.

However, despite what was written about the actions of French governments in Rwanda in the 1990s before, during, and after the genocide, the truth about the responsibility of the then French authorities continues to be obscured. It should be underlined that Mitterrand's personal and his administration's collective neo-colonial engagement in Rwanda viewed the country as a kind of frontier post on the border with rival “Anglo-Saxon” East Africa (Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania) that could help spread French influence in the region.[19] This policy of the then French administration is also underscored in the Duclert report. The report, in this regard, states the following:

“Lastly, a final component of France’s interpretation of the Rwandan situation can be viewed through the prism of defending la Francophonie. Hovering over Rwanda was the threat of an Anglo-Saxon world, represented by the RPF and Uganda, as well as their international allies. This had the effect of inscribing the Rwandan conflict in the search for new balances at the end of the Cold War, on both the global scale and the African continent.”[20] (Emphasis added)

All these clues, lengthy statements in the research report about archive documents, pompous rhetorical concepts in the mentioned report that distract attention from the gist of the issue indicate that the French “l'État profonde”[21] (deep state) tries to cover-up the French authorities' legal responsibilities on the Rwandan Genocide. In this regard, we can refer to the concepts included in the latest Duclert Report. The report, while referring to “serious and overwhelming responsibilities” of French authorities in what had happened in Rwanda, states that these responsibilities are “political, institutional and intellectual nature, as well as ethical, cognitive and moral.”[22] However, the report also underlines that “the French authority demonstrated a continual blindness in their support for a racist, corrupt and violent regime”. (Emphasis added). This judgement points out that the then French authorities willfully, or in more proper terminology “intentionally”, supported the genocidal regime and remained “blind” to the impending genocide to pursue French geopolitical interests.

In the light of the foregoing, it could be asserted that the then French authorities’ responsibilities in Rwandan Genocide cannot only be considered limited to political, institutional, moral, ethical, intellectual, and cognitive ones. These responsibilities also have aspects that directly concern international law. In this context, the provision in Paragraph (e) of Article III of the Genocide Convention stipulating the "complicity in the genocide" as punishable act bears importance.

It is possible to argue that the existence of this provision of the Genocide Convention compelled the authors of the Duclert Report to persistently refer to the concept of "complicity" and to declare that France was not "accomplice" in the Rwandan Genocide, without judging the actual responsibilities of successive French governments. Internationally available evidential information regarding the period when the genocide against the Tutsis took place point out that this statement has no solid basis.

As previously stated, it seems that the French l'État profonde is trying to sweep France's sins under the carpet and while playing this tricky game, to distract the attention from her own sins, unjustly accuses other countries of committing genocide more than a century ago. Doing this, she forgets that genocide is essentially a legal concept that entered the legal vernacular with the 1948 Genocide Convention. This policy, which tries to make people forget the sins of France's registered colonialism, is unlikely to yield results.

In this context, it is useful to remember the following famous line from William Shakespeare’s play The Merchant of Venice: “...Well, old man, I will tell you news of your son. Give me your blessing. Truth will come to light, murder cannot be hid long—a man’s son may, but in the end, truth will out.”[23]

*Photo: Deutsche Welle

[1] Michalopoulos S. and Papaioannou E., “The Scramble For Africa And Its Legacy,” in The New Palgrave Dictionary of Economics, ed. Matias Vernengo and Esteban Perez Caldentey (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), 1–11, 10.1057/978-1-349-95121-5_3041-1.

[2] Daron Acemoglu and James A Robinson, Why Nations Fail: The Origins of Power, Prosperity and Poverty (London: Profile Books, 2012), 237.

[3] United Nations, “Rwanda: A Brief History of the Country,” Infographic, Outreach Programme on the 1994 Genocide Against the Tutsi in Rwanda and the United Nations, 2021, https://www.un.org/en/preventgenocide/rwanda/historical-background.shtml.

[4] Mahmood Mamdani, When Victims Become Killers: Colonialism, Nativism, and the Genocide in Rwanda. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 35.

[5] “Rwandan Genocide,” History.com, September 30, 2019, https://www.history.com/topics/africa/rwandan-genocide.

[6] Vincent Duclert, “La France, le Rwanda et le génocide des Tutsi (1990-1994) - Rapport remis au Président de la République,” Commission de recherche sur les archives françaises relatives au Rwanda et au génocide des Tutsi (Armand Colin, March 26, 2021), 965, https://www.vie-publique.fr/sites/default/files/rapport/pdf/279186.pdf.

[7] The United Nations Security Council established the United Nations Assistance Mission for Rwanda (UNAMIR) on 5 October 1993, through its Resolution 872. The mandate was to support the parties complying with the Arusha Peace Agreement, including assisting in maintaining security in the Rwandan capital, Kigali, establishing demilitarized zones and demobilization procedures, and monitoring the security situation in the last phases of the transitional government. With the outbreak of the genocide and renewal of the civil war, Resolution 912 (21 April 1994) expanded UNAMIR’s mandate to allow it to act as an intermediary to arrange a ceasefire, assist in the resumption of humanitarian activities, and monitor the safety and security of civilians who sought refuge with UNAMIR.

[8] Roméo Dallaire, Shake Hands With the Devil: The Failure of Humanity in Rwanda (New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2004), 293.

[9] UN Security Council, “Adopted by the Security Council at Its 3392nd Meeting, on 22 June 1994” (United Nations, June 22, 1994), S/RES/929 (1994), https://www.refworld.org/docid/3b00f15c50.html.

[10] Philipp Sandner, “France and Rwanda: Re-Examining France’s Role in the Genocide,” Deutsche Welle, June 22, 2021, sec. Africa, https://www.dw.com/en/france-and-rwanda-re-examining-frances-role-in-the-genocide/a-49086564.

[11] Monique Abrishami, Julie Baleynaud, and Scott Brooks, “A Foreseeable Genocide: The Role Of The French Government In Connection With The Genocide Against The Tutsi In Rwanda” (Washington, D.C.: Levy Firestone Muse LLP, April 19, 2021), 567, https://www.gov.rw/fileadmin/user_upload/gov_user_upload/2021.04.19_MUSE_REPORT.pdf.

[12] Duclert, “La France, le Rwanda et le génocide des Tutsi (1990-1994) - Rapport remis au Président de la République,” 977–78.

[13] Duclert, 982.

[14] Mehdi Ba, “Vincent Duclert: ‘In Rwanda, France Dismissed Reality,’” The African Report, April 7, 2021, https://www.theafricareport.com/77982/vincent-duclert-in-rwanda-france-dismissed-reality/.

[15] Abrishami, Baleynaud, and Brooks, “A Foreseeable Genocide: The Role Of The French Government In Connection With The Genocide Against The Tutsi In Rwanda,” 535.

[16] Duclert, “La France, le Rwanda et le génocide des Tutsi (1990-1994) - Rapport remis au Président de la République,” 971–72.

[17] “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide: Human Rights,” December 9, 1948, vol. 78, p. 277, https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-1&chapter=4&clang=_en.

[18] Elysee, “Élysée. Discours du Président Emmanuel Macron depuis le Mémorial du génocide perpétré contre les Tutsis en 1994” (Elysee, Mai 2021), https://www.elysee.fr/emmanuel-macron/2021/05/27/discours-du-president-emmanuel-macron-depuis-le-memorial-du-genocide-perpetre-contre-les-tutsis-en-1994.; Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, “Rwanda - Speech by President Emmanuel Macron at the Kigali Genocide Memorial (Kigali, 27 May 2021)” (Ministère de l’Europe et des Affaires étrangères, May 27, 2021), https://www.diplomatie.gouv.fr/en/country-files/rwanda/news/article/rwanda-speech-by-president-emmanuel-macron-at-the-kigali-genocide-memorial.

[19] Abrishami, Baleynaud, and Brooks, “A Foreseeable Genocide: The Role Of The French Government In Connection With The Genocide Against The Tutsi In Rwanda,” 569.

[20] Duclert, “La France, le Rwanda et le génocide des Tutsi (1990-1994) - Rapport remis au Président de la République,” 984.

[21] Marc Semo, “L’« Etat profond », ou le fantasme d’une administration parallèle,” Le Monde, September 11, 2019, sec. Opinions - Diplomatie, https://www.lemonde.fr/idees/article/2019/09/11/l-etat-profond-ou-le-fantasme-d-une-administration-parallele_5508858_3232.html.

[22] Duclert, “La France, le Rwanda et le génocide des Tutsi (1990-1994) - Rapport remis au Président de la République,” 965.

[23] The Merchant of Venice, Updated edition (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2010), 51.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

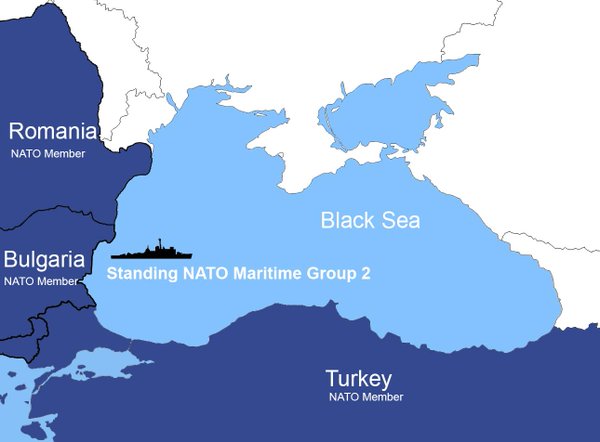

BLACK SEA, A POTENTIAL FRICTION VENUE BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE WEST: TURKEY HOLDS THE KEY TO THE REGION

BLACK SEA, A POTENTIAL FRICTION VENUE BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE WEST: TURKEY HOLDS THE KEY TO THE REGION

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 13.03.2017 -

GOLDEN DAWN IS ATTEMPTING TO REGAIN A PRESENCE IN GREECE WITH A FOCUS ON NORTHERN GREECE AND WESTERN THRACE

GOLDEN DAWN IS ATTEMPTING TO REGAIN A PRESENCE IN GREECE WITH A FOCUS ON NORTHERN GREECE AND WESTERN THRACE

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 15.03.2023 -

GUARDIANSHIP OR EQUILIBRIUM? POWER, AND THE LEGACY OF ORDER IN THE BLACK SEA

GUARDIANSHIP OR EQUILIBRIUM? POWER, AND THE LEGACY OF ORDER IN THE BLACK SEA

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 02.09.2025 -

50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE CYPRUS PEACE OPERATION: WHAT PROPOSAL DID THE GREEK SIDE MAKE TO RAUF DENKTAŞ IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE OPERATION?

50TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE CYPRUS PEACE OPERATION: WHAT PROPOSAL DID THE GREEK SIDE MAKE TO RAUF DENKTAŞ IMMEDIATELY AFTER THE OPERATION?

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 25.07.2024 -

GREEK POLICIES TOWARDS TURKISH MINORITY SCHOOLS RISK REPEATING HISTORY

GREEK POLICIES TOWARDS TURKISH MINORITY SCHOOLS RISK REPEATING HISTORY

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 19.08.2025

-

SOVEREIGNTY AND SYNERGY: INTEGRATING MONTREUX CONVENTION COMPLIANCE INTO EU BLACK SEA SECURITY ARCHITECTURE

SOVEREIGNTY AND SYNERGY: INTEGRATING MONTREUX CONVENTION COMPLIANCE INTO EU BLACK SEA SECURITY ARCHITECTURE

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 01.07.2025 -

INDIA’S STRATEGIC BALANCING CHALLENGES THE QUAD

INDIA’S STRATEGIC BALANCING CHALLENGES THE QUAD

Özge Emine ÖZÇELİK 21.01.2026 -

NEW LEADERS FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION HAVE BEEN APPOINTED

NEW LEADERS FOR THE EUROPEAN UNION HAVE BEEN APPOINTED

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 06.08.2019 -

REVIVAL OF THE QATAR-TÜRKİYE NATURAL GAS PIPELINE PROJECT

REVIVAL OF THE QATAR-TÜRKİYE NATURAL GAS PIPELINE PROJECT

Bekir Caner ŞAFAK 16.04.2025 -

SHIFTING PARADIGMS: ELECTION INTERFERENCE AND DEMOCRATIC INTEGRITY IN THE OSCE REGION

SHIFTING PARADIGMS: ELECTION INTERFERENCE AND DEMOCRATIC INTEGRITY IN THE OSCE REGION

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 24.01.2025

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"