In a review article published in the latest issue of Middle East Journal (Spring 2020), Professor Michael M. Gunter takes to task two Israeli scholars, Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi, for the outright bias and double standard in their book The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924.[1] This is a significant development, given both Professor Gunter’s reputation as a balanced scholar and Middle East Journal’s reputation as the leading journal in the field of the Middle East studies.

After a brief introduction, summarizing the contents and the scope of the book for the readers, Gunter moves on to the main theme of the book and lists the shortcomings of the authors’ study. The authors fail to critically engage with their sources and, more importantly, they cannot substantiate their charges even on the basis of these biased sources. As Gunter writes:

“[D]espite their frequent assertions and implications, they fail to prove that the Ottoman authorities ordered these horrific deeds, as opposed to their resulting from the primitive state of Ottoman resources that led to what might be termed ‘criminal deaths’ due to local vendettas, robberies, neglect, starvation, etc. The authors also largely gloss over too blithely or simply ignore solid counterarguments and evidence that the Christians often gave as much as they received.”

Moreover, the author’s bundling of disparate and unrelated events and historical figures in an effort to the portray Turkey and the Turks as the invariable evil further shows the authors’ biases. Professor Gunter admirably captures this double standard:

“if we are going to speak about a continuing genocide whose roots date back well before World War I, it is only fair to start with the deportations and mass killings of Muslims from the Balkans by the newly created Christian states, beginning with the Greek war of independence in the 1820s and followed by the ethnic cleansing of the Caucasus in 1864, Bulgaria in 1877–78, and present-day northern Greece and Macedonia in 1912–13. In this period several million Muslim refugees (known as muhacirler in Turkish) were deported to present-day Turkey or murdered in situ, a dynamic that helped lead to fear and hatred of Christians in Anatolia. In addition, the Serbian genocidal attacks against Bosnian Muslims in the 1990s might also be viewed as a modern-day continuation of these earlier acts.”

Gunter similarly notes the authors’ selective discussion of the topics, ignoring historical context and contingency and thus misrepresenting the chain of events leading to the catastrophic periods in history. He notes for example that the two authors clearly ignore the well-known provocations carried out by the Armenian political committees in the events of the 1890s. Likewise, the two authors fail to mention that upon gaining independence after the First World War, one of the first things that the newly found Armenian Republic did was to declare war on Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey in order to gain more territory, yet they declare the Turkish victory over the Armenian Republic as a “renewed genocide.” A similar double standard is also visible in the authors’ discussion of the Greek invasion of western Anatolia as Gunter observes:

“Moreover, to term Mustafa Kemal’s desperate and heroic existential struggle against the ethnic cleansing perpetrated by the invading Greeks that began in 1919 with British support and that drove to within 50 miles of Ankara in central Anatolia before finally being halted and pushed back into the sea a “genocide” is a revealing example of the authors’ biases. Further ignored is Mustafa Kemal’s magnanimous refusal to trample upon an enormous Greek flag his troops threw before him after he retook Smyrna from the invading Greeks. Instead, the founder of the modern Republic of Turkey used his victory to commence a reconciliation with Greece and its prime minister, Eleftherios Venizelos.”

Michael M. Gunter ends his article with the hope that his review will encourage further and more balanced research on the Armenian Question and concludes that this book deserves a cautious reading due to its “one-sided … damning diatribes against the Turks” and its being “an example of misguided Orientalism.”

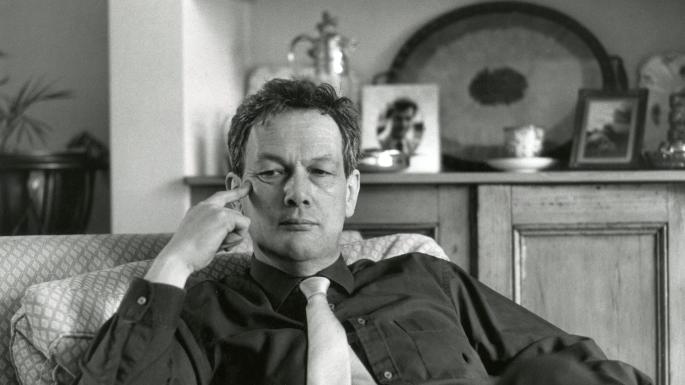

*Photo: Professor Michael M. Gunter

[1] Benny Morris and Dror Ze’evi, The Thirty-Year Genocide: Turkey’s Destruction of Its Christian Minorities, 1894–1924 (London: Harvard University Press, 2019), ISBN-13: 978-0674916456.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

AVIM’S CONFERENCE ENTITLED SECURITY AND STABILITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH CAUCASUS

AVIM’S CONFERENCE ENTITLED SECURITY AND STABILITY CONCERNS IN SOUTH CAUCASUS

WHAT DID THE FRENCH PRESIDENT IMPLY WITH THE “ARMENIAN FILE”

WHAT DID THE FRENCH PRESIDENT IMPLY WITH THE “ARMENIAN FILE”

AKÇAM'S DISTORTIONS CONTINUE

AKÇAM'S DISTORTIONS CONTINUE

BIASED DISPARAGEMENT OF THE LATE NORMAN STONE BY TWO BRITISH DAILIES

BIASED DISPARAGEMENT OF THE LATE NORMAN STONE BY TWO BRITISH DAILIES

DISTURBING PUBLICATION TREND AT PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

DISTURBING PUBLICATION TREND AT PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

HISTORIAN AND DIPLOMAT BİLAL N. ŞİMŞİR

HISTORIAN AND DIPLOMAT BİLAL N. ŞİMŞİR

THE MESSAGE OF THE PRIME MINISTER

ORTHODOX COUNCIL TO MEET AFTER 1200 YEARS

ORTHODOX COUNCIL TO MEET AFTER 1200 YEARS

THE DRAFT RESOLUTION APPROVED BY THE POLITICAL AFFAIRS COMMITTEE OF PACE

THE DRAFT RESOLUTION APPROVED BY THE POLITICAL AFFAIRS COMMITTEE OF PACE

PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN ARMENIA AND THE IRREGULARITIES TOLERATED BY THE EU

PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN ARMENIA AND THE IRREGULARITIES TOLERATED BY THE EU