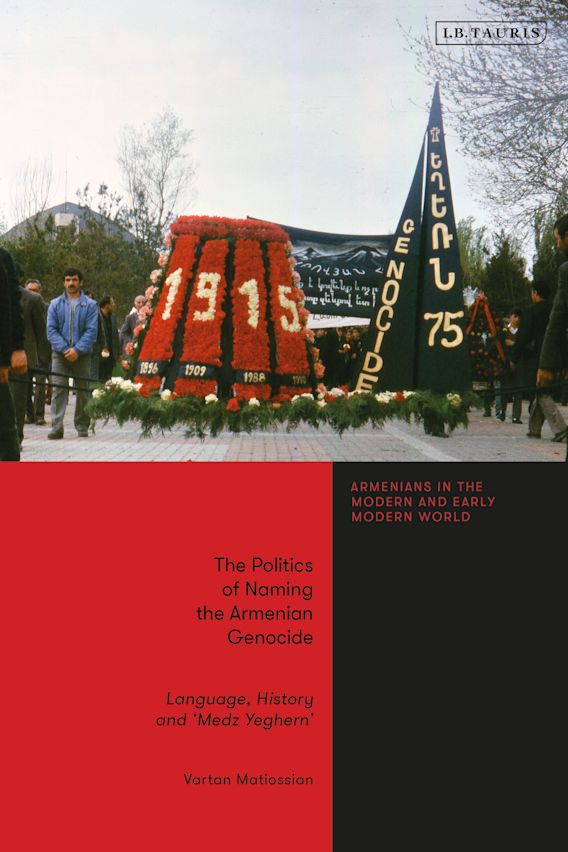

The events of 1915 and the fate of the Ottoman Armenians in the Ottoman Empire during the First World War continue to remain a question of dispute among the scholars. In a recent publication titled The Politics of Naming the Armenian Genocide: Language, History and ‘Medz Yeghern’ (London: I.B Tauris, 2021), Armenian scholar Vartan Matiossan makes an unconvincing case that the Armenian phrase “Medz Yeghern” (Great Catastrophe) was actually the exact Armenian term meeting the concept of “genocide” until the word was invented much later in the 1948 Genocide Convention. It is difficult to accept this view not only because the concept of genocide is a strictly defined legal term that cannot be applied retrospectively but also because the sacralization of the term and its application to the events of 1915 by the Armenians took place much later around 1960s with a great deal of Soviet manipulation.

In the modern arena, accusations of genocide are most often leveled by political lobbying groups to earn international public support and sympathy for their cause and to delegitimize their opponents’ stance over the regional conflicts. Thus, as Michael Gunter argued, although “genocide” can be a useful concept from the legal point of view, “the term has also been overused, misused, and therefore trivialized by many different groups including the Armenians seeking to demonize their antagonists and win sympathetic approbation for themselves.”

There is no doubt that the Armenian accusations of genocide fall under this category. Before 1960s, not only did the Armenians refrain from using the term popularly but also their references to the “Medz Yeghern” cannot be taken as equivalent for the term genocide. When the Turkish President Celal Bayar paid an official visit to the United States in the 1954, he was welcomed and greeted by the Armenians (former citizens of the Ottoman Empire) as their own, surely a curious fact in the case of a people who had firsthand experience of the turmoil of the First World War and who supposedly held the government responsible with such a grave accusation.

Moreover, even Armenian publications usually switched using terms around 1965. For example, an Armenian committee called “the Commemorative Committee on the 50th Anniversary of the Armenian Massacres” published a series of books and booklets on the events of 1915. But later on, the committee’s English name was changed to “the Commemorative Committee on the 50th Anniversary of the Turkish Genocide of the Armenians”, even though its Armenian version still remained the same some 17 years after the Genocide Convention was adopted by the United Nations in 1948. This no doubt shows that the motivation to use the term genocide was political and did not stem from a need to find a better corresponding term for Medz Yeghern.

At this point, it might be necessary to remind the readers that in addition to garnering global support for the Armenian cause, the accusations of genocide fulfill another important function for the Armenian Diaspora. As Brandon Cannon observes; “the Armenian Diaspora communities, in large part rely on and gain succor from the traumatic events of 1915 because they provide the only glue that binds these disparate linguistic, religious and geographically atomized communities together.” In other words, “to have these events recognized as genocide... [is] the only bond strong enough to bind the otherwise territorially, linguistic and religiously diverse Diaspora communities together.” Thus, the maintenance of hatred towards Turks and the keeping the Armenian identity closely tied to the genocide accusations provides the Armenian Diaspora with an opportunity to keep the Armenian identity alive and protect it against assimilation in many different countries.

Armenian nationalists also find it difficult to accept that the leaders and representatives of the different states use the term “Medz Yeghern” in the sense that it refers to a “great calamity” rather than (as they would prefer) a “great crime”, since they feel the first interpretation merely recognizes the Armenian suffering without properly and clearly denouncing the Turks, thus conflicting with their agendas to demonize the Turkish people and state.

Despite the Armenian nationalist arguments to equate the Medz Yeghern and the legal term of genocide, the two are essentially different expressions. Genocide reflects a strictly defined legal term whereas the Medz Yeghern is a term that connotes a tragedy they went through. It connotes victimhood, but not necessarily an accusation on the causes. Hovhannes Katchaznouni, the first Prime Minister of the first Republic of Armenia has his own interpretation that can be summed up as “we brought it onto ourselves”.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

THE BRAZILIAN MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS HAS DISAPPOINTED ARMENIA

THE BRAZILIAN MINISTER OF FOREIGN AFFAIRS HAS DISAPPOINTED ARMENIA

NO PAUSE IN PATHOLOGICAL OBSESSION WITH TURKEY EVEN IN TIME OF THE CORONA VIRUS PANDEMIC

NO PAUSE IN PATHOLOGICAL OBSESSION WITH TURKEY EVEN IN TIME OF THE CORONA VIRUS PANDEMIC

AVIM WEBINAR VIDEO REMOVED FROM A SOCIAL MEDIA PLATFORM HAS BEEN REINSTATED

AVIM WEBINAR VIDEO REMOVED FROM A SOCIAL MEDIA PLATFORM HAS BEEN REINSTATED

ARMENIAN MYTHS ARE DOOMED TO FAILURE: THE TRUTH WILL PREVAIL

ARMENIAN MYTHS ARE DOOMED TO FAILURE: THE TRUTH WILL PREVAIL

THE ARMENIAN REVOLUTIONARY FEDERATION’S EMBRACE OF TERRORISM

THE ARMENIAN REVOLUTIONARY FEDERATION’S EMBRACE OF TERRORISM

ATTEMPTS AT DIASPORIZING TURKISH ARMENIANS – III

ATTEMPTS AT DIASPORIZING TURKISH ARMENIANS – III

WATS AND THE TEFLON LINING TO WHICH NOTHING STICKS

WATS AND THE TEFLON LINING TO WHICH NOTHING STICKS

CO-FOUNDER OF THE ARMENIAN REVOLUTIONARY FEDERATION AND ONE OF THE PRECURSORS OF ARMENIAN TERRORISM: KRISTAPOR MIKAELYAN

CO-FOUNDER OF THE ARMENIAN REVOLUTIONARY FEDERATION AND ONE OF THE PRECURSORS OF ARMENIAN TERRORISM: KRISTAPOR MIKAELYAN

KAZAKHSTAN'S ECONOMIC AND FOREIGN POLICIES: NOTES FROM ASTANA - I

KAZAKHSTAN'S ECONOMIC AND FOREIGN POLICIES: NOTES FROM ASTANA - I