In the latest issue of the Journal of Muslim Minority Affairs, Turkish historian Yücel Güçlü published a very interesting and informative article titled “Jewish Salonica in 1912 and 1943: The Ottoman and Greek/German Practices Considered.” The article compares the treatment of Jews in Salonica (Thessaloniki) by Ottoman to that of post-Ottoman administrations.

The majority of Salonica Jews consisted of Sephardi Jews whose ancestors escaped from the Iberian Peninsula due to the severe persecution of the Spanish Inquisition. Over time, a variety of Jews fleeing from elsewhere also found refuge in the city, such as the Jews fleeing persecution in Eastern Europe in the late 19th century and the Jews fleeing the pogroms in Kishinev in 1903 and Odessa in 1905. The Ottoman Empire at large and Salonica in particular was thus a safe haven for the Jews. Samuel Cox, the American Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire during 1885–1887, described Salonica as “a paradise for Jews.” Güçlü summarizes the report of the American Ambassador as follows:

“The Jews were partial to the sultan, and the sultan had shown tolerance to them. In order to arrive at a decision in religious and civil cases in a Jewish community, judgments were expected from those most learned in sacred books. These were followed by the Ottoman administration— just as United States courts in several States followed the local laws. Could there be a better system of home rule, Cox wondered. Jew and Mahometan got on admirably together.”

Thus, it is little wonder that the Ottoman Empire earned its reputation as a safe haven for the Jews, and the Jews were not shy in demonstrating their attachment to the Ottoman state, like they had done in 1897 when they had celebrated with enthusiasm the Ottoman victory over Greece. By the early 20th century, the Jews were the dominant element in the city of Salonica, while the Turks constituted the majority of the province of Salonica as a whole. As Güçlü notes:

“a genuine loyalty was felt by all sections of the Jewish population toward the Ottoman fatherland. Jews depended on the continued stability and existence of the Ottoman state, to which they contributed their valuable talents and from which their prosperity derived.”

However, this state of affairs would come to an abrupt end with the Ottoman loss and Greek conquest of Salonica in November 1912. The loss of Salonica was not only a trauma for the Turks but also for the Ottoman Jews who could not help remembering that “since 1860 antisemitic incidents had occurred more frequently, especially among the Greek Orthodox communities.” Closely linking their fate to the Ottoman Empire, at the beginning of the Balkan Wars, the Ottoman Jews “offered public expressions of allegiance” to the Ottoman Empire. As Güçlü notes:

“The chief rabbi of the city, Jacob Meir, who had pronounced a prayer in Turkish for Sultan Reşad just a year earlier, claimed that he ‘would have taken up arms if that had not been an impossibility, in order to prevent the fate which befell the Turks.’ It took a number of years, and concerted government campaigns, to convince the city’s Jews to adopt Greek citizenship and abandon their fezzes in favor of new forms of headgear more compatible with the shifting political landscape.”

Thus, the Ottoman Jews clearly demonstrated their affinity and support for the Turks to the anger of the Greek nationalists. Soon after the Greek occupation of Salonica, anti-semitic articles appeared in Greek newspapers. Synagogues were raided and “Sifrei Torah, the scrolls of the Law, were defiled.” Important Jewish historical monuments were destroyed, while Jewish homes were raided and plundered and “the weekly market held on Monday was transferred to Saturday in order to give an affront to religious Jewish merchants and exclude them from participation.” All of these had been done to intimidate and force the Jews out of Salonica by the Greek administration and many important Jewish families fled to İzmir and İstanbul as a result and many prominent Jews deplored the fact that “the happy times of Ottoman rule were long gone.” And the Salonica Jews now faced not only discrimination, but also physical destruction. Joseph Nehama, Director of the Alliance Israélite Universelle school, reported that “among the Greek population, people are talking about a Jewish massacre.”

During and after the First World War, the Salonica Jews continued to suffer from the discrimination and prejudice of the Greek administration. After the failed Greek invasion of Anatolia in 1919-1922 and the exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey, the Jews were marginalized even more. To provide jobs for Greek migrants from Anatolia, “the Salonica municipality adopted emergency laws that removed Jews from certain spheres of the economy.” These discriminatory practices were later followed by physical violence:

“The Greek press of Salonika and the newspaper Makedonia in particular indulged systematically in anti-Jewish propaganda, polarizing the relations between the two elements. A result of the poisoning of Greek public opinion by the press was the anti-Jewish pogrom against the Campbell neighborhood, where most of the remaining Jews lived. The area was burned to the ground in 1931. The direct result of this was the first mass migration of thousands of Jews to Palestine, reducing the number of the local Jewish population to 56,000, cutting down the Jewish component from 50 percent to 20 percent of the total inhabitants.”

In addition to pogroms, they also had now been deprived of their cultural and educational rights which they had enjoyed for centuries under the Ottoman rule. New regulations “requiring the use of Greek and prohibiting the use of Hebrew and Judeo-Spanish in the Jewish schools” were also introduced. “A start was made also on expropriating the land of the principal Jewish cemetery in Salonika for use by the new university in order to drive the Jews out.” All of these led to the massive flight of the Jews from Salonica to Palestine. Prominent Sephardi Jews now deplored this “new expulsion”, noting that it was “as tragic as that from Spain.”

With the outbreak of the Second World War and the occupation of Salonica by Nazi Germany, the remaining Jewish population of Salonica, now numbering 56,000, was to face much worse. According to estimates, by 1945, no more than 10,000 of the pre-war Jewish population of Greece survived, meaning that “75 percent of the Greek Jewry was annihilated, most having been deported to Auschwitz.” According to Nora Levin, the total death count in all of Greece was over 60,000 Jews, almost total annihilation. The Central Committee of the Jewish Communities in Greece stated just after the war that “87 percent of the pre-war population of 79,950 people” had been killed, bringing the Jewish existence in the city to a tragic end.

The Jewish community at Salonica was the most numerous, important, and prosperous in the Ottoman Empire throughout the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century, and the city’s Jewish population had enjoyed the protection of the Ottoman Empire until the loss of Salonica. The relationship was characterized by mutual respect and benefit. The Ottoman state fully realized that the Jews were one of the chief elements in economic progress and prosperity. The Turks had all along regarded the Jews as loyal elements of the Empire and had placed confidence in them. The Jews of Salonica in turn had borne feelings of gratitude toward the Ottoman Empire and the Turks ever since their flight from Spain into the Ottoman lands hundreds of years previously. But the fate of the Salonica Jews changed for much worse first with the Greek occupation of the city and later much more dramatically during the murderous campaign of the Nazi regime during the Second World War.

*Photograph: A Jewish family from Salonica (1917) - Source: TimesofIsrael.com

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

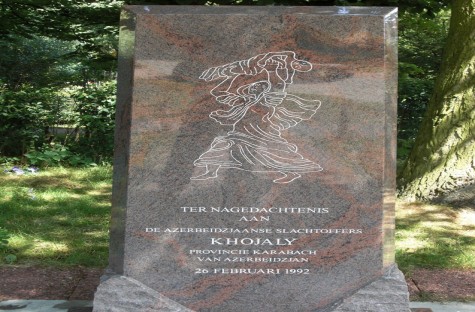

23rd ANNIVERSARY OF THE KHOJALY MASSACRE

23rd ANNIVERSARY OF THE KHOJALY MASSACRE

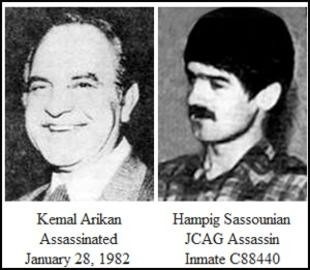

THE PAROLE OF HARRY (HAMPIG) M. SASSOUNIAN, THE PERPETRATOR OF THE MURDER OF TURKEY’S CONSUL GENERAL TO LOS ANGELES KEMAL ARIKAN IN 1982

THE PAROLE OF HARRY (HAMPIG) M. SASSOUNIAN, THE PERPETRATOR OF THE MURDER OF TURKEY’S CONSUL GENERAL TO LOS ANGELES KEMAL ARIKAN IN 1982

RENEWED ATTEMPTS OF THE CURRENT OTSA ADMINISTRATION TO REMOVE THE NAMES OF FUAT KÖPRÜLÜ AND HALİDE EDİP ADIVAR FROM THE OTSA AWARDS

RENEWED ATTEMPTS OF THE CURRENT OTSA ADMINISTRATION TO REMOVE THE NAMES OF FUAT KÖPRÜLÜ AND HALİDE EDİP ADIVAR FROM THE OTSA AWARDS

THE NOTION OF “WESTERN BALKANS”, THE BALKANS, AND TURKEY

THE NOTION OF “WESTERN BALKANS”, THE BALKANS, AND TURKEY

GEORGIA’S ANAKLIA PORT ON THE MIDDLE CORRIDOR ROUTE

GEORGIA’S ANAKLIA PORT ON THE MIDDLE CORRIDOR ROUTE