Brendon J. Cannon, Legitislating Reality and Politicizing History: Contextualizing Armenian Claims of Genocide (Offenbach am Main: Manzara Verlag, 2016).

Brendon J. Cannon’s book Legislating Reality and Politicizing History: Contextualizing Armenian Claims of Genocide published in 2016 is a welcome contribution to the debates surrounding the relocation of Armenians in the Ottoman Empire during World War One. Cannon’s book is not a history of the relocation of the Armenians nor is it a history of the Armenian diaspora. Rather, Cannon focuses primarily on how the events of 1915 have been utilized in the unification of diaspora group identity and consequently how this group identity finds form in political campaigning to have the events of 1915 recognized as genocide. Cannon then shifts his attention to the efforts made to reconcile Turks and Armenians, and concludes with a discussion of how the Armenian diaspora’s campaigning negatively effects relations between Turkey, Armenia and the Armenian diaspora.

Cannon’s primary argument is that the campaigns waged by the Armenian diaspora to have the events of 1915 recognized as genocide are primarily undertaken in an effort to solidify Armenian identity. Cannon writes that consequently the “highly emotional, powerful” campaign is focused not on territory, but on memory (p. 125). This memory serves to unify the diaspora as Armenians are varied in political views, religion and language. This is particularly true for latter generations of Armenians in the diaspora who no longer speak Armenian.

While recording that the events of 1915 are recognized as historical fact by the Armenian diaspora, the Republic of Armenia, much of the North American, Russian and European news media, many politicians and some important scholars, Cannon also writes that there is a significant body of persons, scholars and institutions who argue that this reading of history is “biased, incomplete and mischaracterized” (p. 32).

Therefore, the debates surrounding the events of 1915 are not conducted regarding whether if the events can objectively be categorized as genocide, but are based on two completely opposing narratives as to what occurred. Cannon notes that these debates take place in a highly charged environment, further stating that the “watchwords of ‘denial’ and ‘victimhood’ are ever-present and act as gatekeepers to deflect criticism, stymie critical thinking and discourage further research” (p. 66).

Referring to the Armenian diaspora’s perpetual mobilization in the purpose of genocide recognition, Cannon argues that mobilization is in fact a quest for “identity consolidation” that results in the continued existence of Armenian lobby groups. Cannon posits that this consolidation is guaranteed through the “continued mobilization of the target ethnic group” (p. 37). Thus, the Armenian “self” is now juxtaposed with the “genocidal-perpetrating other: the Turk.” The othering of Turks as “genocide deniers” serves to unify Armenians in a way “Armenian churches, languages and politics cannot” (p. 48). Recognizing that religion, language and politics are not shared by Armenians as a monolith, Cannon argues that “identity informed by a collective trauma” plays a pivotal role in uniting the diaspora.

Cannon discusses the difficulty this creates for talks between concerned parties, “it is precisely those who harness their political objectives to such ideological representations of memory who also brook no opposition to their version of the events of 1915 in the way they were taught to remember them and the political and highly politicized goals encapsulated therein” (p. 65).

The futility of the Armenian recognition campaign as a political demand is demonstrated by the fact it has almost no chance of success. Writing that the campaign lacks concrete demands, Cannon points to a trend in Armenian political literature which argues that genocide recognition must be followed by the Turkish government providing financial compensation and land, yet Cannon also notes that these demands are usually buried below the surface because “irredentism, property claims and money compensation may color or stunt the success of the public relations and legislative engine constructed and harnessed by the Armenian diaspora” (p. 275). On the strategic shortcomings of the Armenian campaign, Cannon also notes that all of the Turkish officials involved in 1915 are long dead and most Armenian survivors are also dead. Therefore, it is unknown what the Armenian diaspora hopes to achieve beyond “purely symbolic and commemorative acts” by convincing legislators to pass laws recognizing the events of 1915 as genocide (p. 256).

Further noting that the Armenian diaspora has refrained from submitting its claims to the relevant international judicial bodies, Cannon explains that this strategy, by avoiding courts and preferring to convince legislators to pass laws informed by “politicized history and definitional elasticity,” has meant that the proponents of the genocide thesis have largely been able to avoid the scrutiny that would “accompany historical and legal investigations” (p. 326).

Resultantly, the Turkish government’s proposal for the establishment of a joint commission to study the events of 1915 has fallen on deaf ears. Cannon argues that this is because the Armenian diaspora’s campaign for genocide recognition by “ad hoc legislation and changes to education curricula” has been successful (p. 266).

Cannon remarks that the lack of a coherent Turkish response can be attributed to a number of factors. He notes that the position of the Turkish diaspora is often reactive, made possible by the comparatively low economic status of Turkish migrants, the fact that Turks maintain a “small presence in most countries outside of Turkey,” and the relative lateness of Turkish migration (p. 283). Cannon writes that another crucial factor is that Turkish identity is not “encumbered by a “same/other” relationship that involves Armenians or other minorities such as Greeks in the Ottoman Empire. Turkish identity is thus “unencumbered by a re-imagined trauma on the scale or import of Armenian diaspora identity” (p. 319).

Above politics, the economic costs of the campaign to have the events of 1915 recognized as genocide are high for all parties concerned, Cannon argues. Turkey maintains a closed border due to Armenia’s occupation of the Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan. Cannon notes that the closure of the border has been criticized by many on both sides who would rather see the issue resolved and tourism and trade flow both ways. Cannon also notes that tens of thousands of undocumented Armenians have found employment in Turkey. Furthermore, Armenia has also been excluded from the energy market, as energy pipelines originating in Azerbaijan and extending to Turkey bypass the country. Yet the resolution of this issue appears impossible, as the Armenian diaspora “brooks no opposition in its quest for Armenian Genocide recognition. The diaspora has proverbially painted itself into a corner from which it cannot escape. Negotiations, let alone the utilization of another descriptive term beyond 'genocide' are construed as an admission of defeat” (p. 319).

In discussing the formation and expression of identity narratives in the Armenian diaspora, Cannon’s work is novel. It is a welcome contribution to the field that tackles questions and narratives that have otherwise remained neglected. While the book is not a work of history, nevertheless a more comprehensive discussion of the formation of Armenian political bodies in the diaspora would have made the book more accessible to those unfamiliar with the subject matter.

BETWEEN SYMBOLIC VICTORY AND COLD REALITY: THE DIVEST TURKEY CAMPAIGN

BETWEEN SYMBOLIC VICTORY AND COLD REALITY: THE DIVEST TURKEY CAMPAIGN

MOVIE WARS: THE TALE OF TWO NARRATIVES

MOVIE WARS: THE TALE OF TWO NARRATIVES

BOOK REVIEW: LEGISLATING REALITY AND POLITICIZING HISTORY

BOOK REVIEW: LEGISLATING REALITY AND POLITICIZING HISTORY

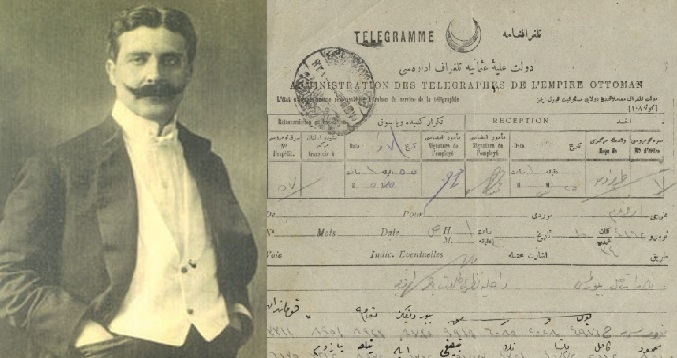

FROM SMOKING GUN TO MUDDIED WATERS: THE ALLEGED TELEGRAM OF BAHAEDDIN ŞAKIR

FROM SMOKING GUN TO MUDDIED WATERS: THE ALLEGED TELEGRAM OF BAHAEDDIN ŞAKIR

ITALIAN REACTION TO THE CAROLINGIAN EU PROJECT

ITALIAN REACTION TO THE CAROLINGIAN EU PROJECT

THE MOLDOVA ELECTIONS AND GAGAUZIA AS A POLITICAL REFLECTION OF THE RUSSIA-EU RIVALRY

THE MOLDOVA ELECTIONS AND GAGAUZIA AS A POLITICAL REFLECTION OF THE RUSSIA-EU RIVALRY

GERMAN-FRENCH JOINT CULTURAL INSTITUTES: TRANSFORMATION OF THE “CIVILIZING” MISSION OF WEST EUROPEAN COLONIALISM

GERMAN-FRENCH JOINT CULTURAL INSTITUTES: TRANSFORMATION OF THE “CIVILIZING” MISSION OF WEST EUROPEAN COLONIALISM

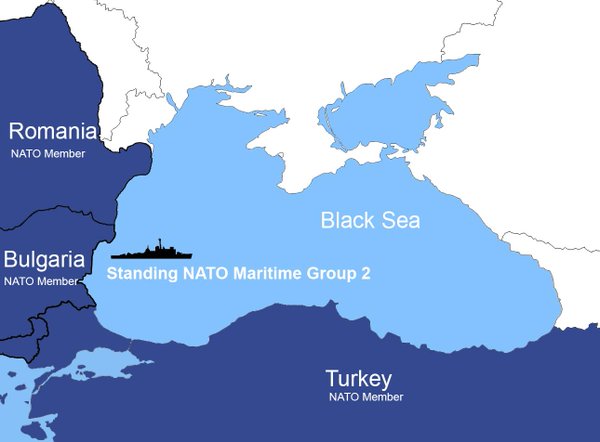

BLACK SEA, A POTENTIAL FRICTION VENUE BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE WEST: TURKEY HOLDS THE KEY TO THE REGION

BLACK SEA, A POTENTIAL FRICTION VENUE BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE WEST: TURKEY HOLDS THE KEY TO THE REGION

GENOCIDE AND GERMANY

GENOCIDE AND GERMANY