Introduction

In May 2021, the discovery of the remains of 215 Indigenous children at the former Kamloops Indian Residential School, which had been run by the Roman Catholic Church, in the province of British Columbia/Canada led to outrage and grief not only in the country but around the world. Some of remains are believed to be of children as young as three. Searches continued after this discovery on the assumption that there might be other unmarked graves. Indeed, in the province of Saskatchewan, 751 unmarked graves were found near the former Marieval Indian Residential School, which had been run by the Catholic Church.[1] This was followed by the discovery of 182 unmarked graves near the former residential St. Eugene's Mission School in British Columbia, which had -just like the previous ones- been run by the Catholic Church.[2] It should be noted that the history of these boarding schools for indigenous children, which was a tool used for the policy of assimilation of the indigenous population, is an important and painful page in the colonial history of Canada.

It should be noted that multiple terminologies have been used for indigenous peoples of Canada and there was constant debate concerning the use of these terms. Among these terms, we can cite the “Aboriginal”, “Indian”, “Native”, “First Peoples”, “First Nations”, and “Indigenous” peoples.[3] According to Section 35 of the 1982 Constitution Act of Canada, “aboriginal peoples” of Canada “includes the Indian, Inuit, and Métis peoples.”[4] Aboriginal peoples, in this sense, is a legal term encompassing all peoples who were the original inhabitants of the lands that now constitute Canada. However, the term aboriginal peoples came to be considered outdated over time and was gradually replaced by the term “indigenous peoples”.

In this context, the commonly accepted terminology for these people is indigenous peoples, in the plural, following the guidelines of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). UNDRIP was adopted by the UN General Assembly on 13 September 2007, by a majority of 144 states in favor, 4 votes against (Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States) and 11 abstentions. However, since adoption of the Declaration, Canada and the other three countries who opposed the Declaration have all reversed their positions and expressed support for it.[5] To better understand the reason for this initial “No” vote, it is necessary to briefly touch upon the colonial policy of the British Empire.

The Discovery Doctrine was a framework used by western European colonists to justify their claims on the territories they explored that were uninhabited by Christians. In this doctrine, since indigenous peoples were not Christian, they were deemed nonhuman and thus their land could be freely seized in line with a concept known as terra nullius, which is a Latin term meaning “land belonging to no one.”[6] The United Nations in 2012 denounced the Doctrine of Discovery as “the fifteenth century Christian principle... [that was the] ‘shameful’ root of all the discrimination and marginalization indigenous peoples faced today.”[7]

Under the colonial vision of the British Empire, the indigenous peoples of Australia, Canada, and New Zealand became minorities in their respective countries in the 19th century. In this vision, these people were to be “civilized”, and to be civilized, they had to be Christian and assimilated. In this context, children received particular attention under the policy of assimilation, as there has always been a special interest in shaping the next generation. The missionaries, teachers, and social workers who carried out this work were motivated by the desire to “save” these people, but in the process, children were forcibly uprooted from their families, communities, language, and culture. In fact, in the second half of the 20th century, removing children from their parents to change a people and a culture came to be recognized as an act of oppression and formally considered by the UN as a type of genocide. In this regard, the 1948 UN Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (Article II/e) considers “forcibly transferring children of the group to another group” as an act of genocide.[8]

Residential School System in Canada Based on Colonial Assimilation Policy

Academic literature on residential schools in Canada takes the roots of this system back to the "Frenchification" (to make French) policy and practices of the French colonizers in the early 17th century.[9] In that respect, it is stated that both the "civilization" policy and the residential school practice were brought to Canada initially by the French colonial administration.[10] Academic sources assert that the French tried to force the natives to adopt Christianity, learn about French civilization and to get used to an “orderly life” based on French culture. It is also stated that the most important purpose of this policy was to ensure the indigenous population’s “recognition of and submission to the authority and domination of the Crown of France.”[11] As per these sources, this policy of Frenchification initially aimed at the creation of a single “race” as a mixture of a cultured indigenous population living in integrated villages together with French immigrants. Later, the strategy was changed to the creation of reserved settlements under missionary supervision. To this end, theological seminaries were established by various Christion sects like the Jesuits. Such schools taught indigenous children mainly the Christian religion and the French language, with the aim of raising them as French. However, there was strong resistance to these schools, due to parental reluctance to give up their children, the large number of school dropouts, and student deaths from European diseases. As a result, this system of forced education failed during the French colonial rule.

After France's defeat in the Seven Years' War and the ceding of nearly all its North American possessions to the United Kingdom (Britain) with the Treaty of Paris in 1763, the British Empire tightened its control over autonomous colonies, and in response to the rebellion of the indigenous peoples, halted the expansion of western European settlers and published the Royal Proclamation. This interim period continued until the War of 1812 between the US and the UK. Later, British policy towards indigenous peoples shifted to “civilizing” the them through education in the 1830s, as the French had sought to do in the previous century. In that regard, the colonial government began the establishment and operation of schools for indigenous peoples and numerous new schools were opened.

The operation of these schools was largely left in the hands of missionary organizations, and the costs for building and running schools was mainly shared between the colonial government and missionary groups. Under the British North American Act of 1867, all aspects of indigenous peoples’ affairs became the responsibility of the Canadian federal government, including education.[12] Within the framework of this responsibility, the government began to establish additional residential schools across Canada in conjunction with other federal assimilation policies. Authorities frequently placed children to schools far from their home communities, part of a strategy to alienate them from their families and familiar surroundings. In 1920, under the Indian Act, it became mandatory for every indigenous child to attend a residential school and illegal for them to attend any other educational institution.[13] By the 1930s, the federal government had come to the internal conclusion that the residential school system was failing to meet its goals.[14] Then came a period when the purpose of education in these schools shifted from assimilation to integration.[15] However, the removal of indigenous children from their families by state authorities continued through much of the 1960s and 70s. Although there was occasional arguments over the closure of these schools, residential schooling survived largely intact until the end of the 1960s and the operation of the residential schools was extended by the continued support they received from the churches, particularly the Roman Catholic Church (which enjoyed preferential treatment especially in the Francophone province of Quebec until the Quiet Revolution of 1960s), which opposed the federal government’s school closure and integration policy.[16]

In 1969, the Department of Indian Affairs took exclusive control of the system, marking an end to church involvement in residential schooling. In the meantime, the government decided to phase out segregation and began incorporating indigenous students into public schools. Starting in 1969, residential schools in Canada began to decline in numbers. In 1970, the Department calculated 56 remaining schools. By 1980, the same institution reported 16, and one decade later, 11. In 1996, Gordon Reserve Indian Residential School in Saskatchewan, the last of its kind, was closed and demolished. By 1999, the Department registered no remaining residential schools in operation.[17] In short, the residential school system officially operated from the 1880s into the 1990s.

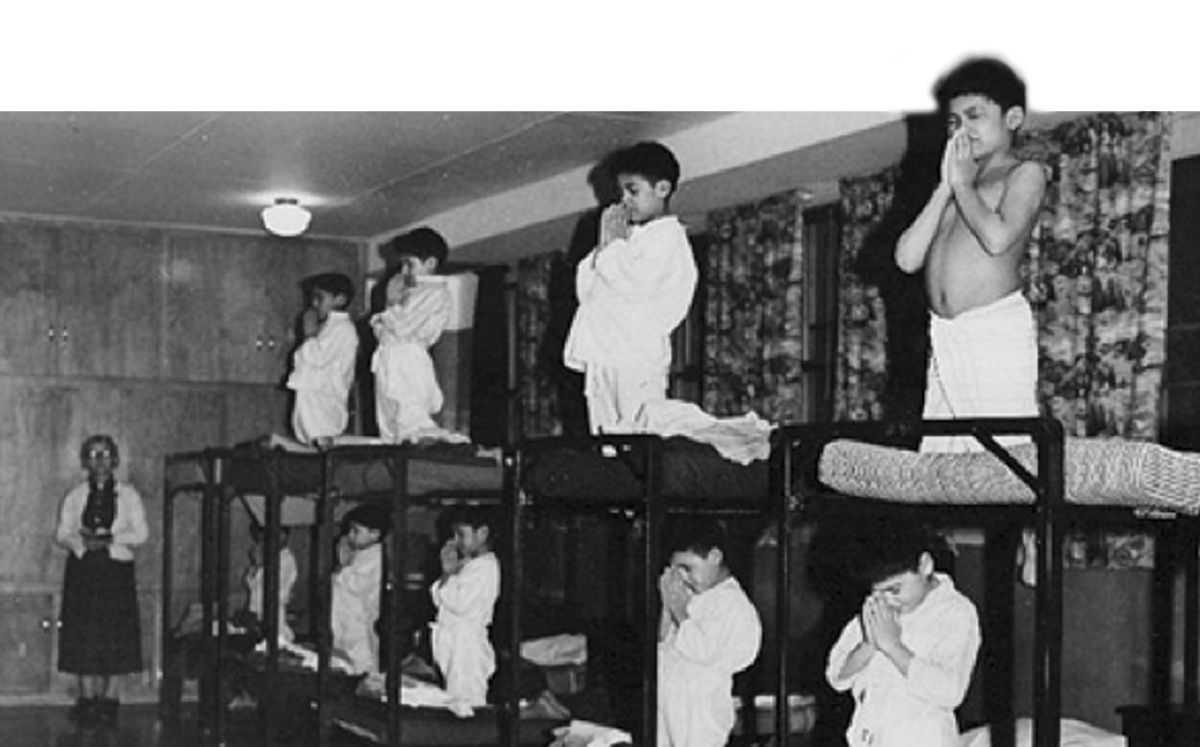

According to the evaluations of the indigenous peoples, this residential school system forcibly separated children from their families for extended periods of time and forbade them to acknowledge their heritage and culture or to speak their own languages. Children were severely punished if these strict rules were broken. Former students at these residential schools have spoken of horrendous physical, sexual, emotional, and psychological abuse at the hands of the school staff. These schools provided indigenous students with inappropriate education, often only enough to acquire lower grades, that focused mainly on prayer and manual labor in agriculture, light industry such as woodworking, and domestic work such as laundry work and sewing.[18]

The Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement and The Truth and Reconciliation Commission

To investigate the indigenous peoples of Canada’s relationship with the rest of the country, the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples (RCAP) was established in 1991. RCAP issued its final report in 1996 and dedicated an entire chapter of the report to residential schools.[19] The 4000-page document made 440 recommendations calling for changes in the relationship between indigenous people, non-indigenous people, and governments in Canada.[20]

In May 2006, the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA) was formally approved by all parties involved. Under the terms of the agreement, former residential school students were provided monetary compensation in the form of a “common experience payment” along with additional compensation based on their years of attendance at a residential school. The agreement also established an Independent Assessment Process for former students to pursue claims of sexual and physical abuse, provided 125 million Canadian dollars for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation to continue their healing programs, granted additional funding to support local and national commemoration projects, and included provisions for the establishment of a 5-year Truth and Reconciliation Commission.

In June 2008, the federal government finally issued a formal apology for its role in the creation and operation of the residential school system. Furthermore, the churches involved in operating residential schools also issued formal apologies. The United Church of Canada was the first to apologize in 1986. Following suit, in 1991 the Anglican Church, the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops, and the Missionary Oblates of Mary Immaculate offered their apologies, while the Presbyterian Church also apologized in 1994. The Roman Catholic Church has yet to issue an apology in this regard. However, pressure has mounted on the Catholic Church to do so (including from the Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau), especially after the discovery of the unmarked graves near St. Eugene's Mission School. It is not known how the Church will respond to these pressures. A delegation of the affected indigenous peoples will reportedly travel to the Vatican in December of this year to hold a meeting with Pope Francis, spiritual leader of the Roman Catholic Church, and request a papal apology.[21] It should also be noted that, following the discovery of the unmarked graves and the subsequent public outrage, multiple Roman Catholic churches in Canada have been vandalized and subjected to arson attacks.[22]

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission in its final report described the residential school system as a “cultural genocide”.[23] The Commission report in this regard states the following:

“For over a century, the central goals of Canada’s Aboriginal policy were to eliminate Aboriginal governments; ignore Aboriginal rights; terminate the Treaties; and, through a process of assimilation, cause Aboriginal peoples to cease to exist as distinct legal, social, cultural, religious, and racial entities in Canada. The establishment and operation of residential schools were a central element of this policy, which can best be described as ‘cultural genocide’. [emphasis added by author]

Physical genocide is the mass killing of the members of a targeted group, and biological genocide is the destruction of the group’s reproductive capacity. Cultural genocide is the destruction of those structures and practices that allow the group to continue as a group. States that engage in cultural genocide set out to destroy the political and social institutions of the targeted group.”[24] [The 1948 Genocide Convention only defines the term “genocide” and does not include genocides with adjectives. For this reason, terms such as “physical/biological/cultural genocide” currently have no recognition under international law]

Conclusion

It is a generally accepted view that colonialism was undertaken to meet the perceived needs of the European imperial powers.[25] However, when the history of imperialism is examined, it will be seen that the imperialist countries, which are always presented as European powers, are essentially the western European countries. Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States are all offshoots of one of these imperialist western European countries, the United Kingdom.

As the above explanations reveal, the basic justification for colonialism was the alleged need to impose Christianity and a Euro-centric understanding of civilization based on the belief system of Christianity to the indigenous peoples. It should be underlined that there was neither moral nor legal ground to impose Christianity onto the indigenous peoples of the world. Besides, the Doctrine of Discovery cannot serve as the basis for a legitimate claim to the lands that were colonized, which were inhabited by the indigenous peoples for thousands of years. Indigenous peoples had their own local political, economic, and cultural systems that met their needs and they did not need or request to be “civilized” or Christianized.

Taken as a whole, the colonial process was justified on the supremacist presumption of taking a specific set of the then western European beliefs and values and proclaiming them to be universal values that could be imposed upon the indigenous peoples of the world.[26] This universalization of western European values that was extended to the other continents served as the prime justification and rationale for the imposition of a residential school system on the indigenous peoples. In this respect, the Canadian residential school system imposed on the indigenous peoples is part of the history of imperialism of the past centuries. In fact, education was both a target and tool of colonialism and was employed as a colonial structure that served as a vehicle for wider imperialist ideological objectives.

In today's world, it is still possible to talk about supremacist colonialist type approaches that take a certain set of western European beliefs and values, present them as universal norms and values, and through various means, try to impose them on the peoples of other countries. In this context, it is thought that all colonialist countries of the past centuries must face the sins of their past, as Canada did and still does on the issue of residential school practice. Canada, which has had until now a solid reputation for being one of the most democratic and pluralistic countries in the world, will be forced to engage in a lot of soul searching in the coming years.

As for the Roman Catholic Church, representing the largest and most powerful Christian denomination in the world, it was instrumental in the spread and imposition of western European colonialism. Before the discovery of the unmarked graves of the indigenous children in Canada, the Church had already been embroiled in a sexual abuse scandal spanning multiple countries in the last two-three decades. It seems that the Church is now faced with another massive scandal. It remains to be seen how the Church will be able to salvage its reputation that has been tarnished by these two scandals.

*Photograph: https://www.thestar.com/

[1] Holly Honderich, “Why Canada Is Mourning the Deaths of Hundreds of Children,” BBC News, July 2, 2021, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-57325653.

[2] Alex Migdal, “182 Unmarked Graves Discovered near Residential School in B.C.’s Interior, First Nation Says,” CBC News, June 30, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/bc-remains-residential-school-interior-1.6085990.

[3] “Terminology of First Nations, Native, Aboriginal and Metis” (Aboriginal Infant Development Program, July 14, 2010), https://web.archive.org/web/20100714021655/http://www.aidp.bc.ca/terminology_of_native_aboriginal_metis.pdf.

[4] “Constitution Act, 1982” (The Solon Law Archive, June 28, 2019), Part I Canadian Charter Of Rights And Freedoms, https://www.solon.org/Constitutions/Canada/English/ca_1982.html

[5] United Nations General Assembly, “United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples” (United Nation Department of Economic and Social Affairs, September 13, 2007), A/61/L.67, https://www.un.org/development/desa/indigenouspeoples/declaration-on-the-rights-of-indigenous-peoples.html.

[6] Alberta Teachers Association, “Concepts And Policies Of Assimilation,” Information site, Chapter 17: Concepts And Policies Of Assimilation, accessed July 1, 2021, https://www.teachers.ab.ca/SiteCollectionDocuments/ATA/For%20Members/ProfessionalDevelopment/Walking%20Together/PD-WT-16q%20Policies%20of%20Assimilation-WEB.pdf.

[7] United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, “Impact of the ‘Doctrine of Discovery’ on Indigenous Peoples” (United Nations, June 1, 2012), https://www.un.org/en/development/desa/newsletter/desanews/dialogue/2012/06/3801.html.

[8] Andrew Armitage, Comparing the Policy of Aboriginal Assimilation. Australia, Canada, and New Zealand., 1st ed. (Vancouver: UBCPress, 1995), 2–6.

[9] John S. Milloy, A National Crime: The Canadian Government and the Residential School System, Illustrated edition, Manitoba Studies in Native History /Critical Studies in Native History 2 (University of Manitoba Press, 1999), 13–14.

[10] Milloy, 14.

[11] J. Jaenen Cornelius, “Education for Francization: The Case of New France in the Seventeenth Century,” in Indian Education in Canada, ed. J. Barman Y, Y Hébert, and D. McCaskill, vol. The Challange, 1 vols., Nakoda Institute Occasional Paper 2 (Vancouver: UBC Press, 1986).

[12] Jerry P. White and Julie Peters, “A Short History of Aboriginal Education in Canada” (Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCI), 2009), 15–17, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/61687944.pdf.

[13] Erin Hanson, Daniel P. Games, and Alexa Manuel, “The Residential School System,” Indigenous Foundations, 2020, 7.

[14] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 2 1939 to 2000 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015), 3, https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Volume_1_History_Part_2_English_Web.pdf.

[15] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 10.

[16] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 11.

[17] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 103.

[18] Hanson, Games, and Manuel, “The Residential School System.”

[19] “A Timeline of Residential Schools, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission,” CBC News, May 16, 2008, https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/a-timeline-of-residential-schools-the-truth-and-reconciliation-commission-1.724434.

[20] Mary C. Hurley and Jill Wherrett, “The Report Of The Royal Commission On Aboriginal Peoples” (Parliamentary Research Branch, October 1999), PRB 99-24E, https://publications.gc.ca/Collection-R/LoPBdP/EB/prb9924-e.htm.

[21] Migdal, “182 Unmarked Graves Discovered near Residential School in B.C.’s Interior, First Nation Says.”

[22] Elizabeth Thompson, “‘Unacceptable and Wrong’: Trudeau Condemns Attacks on Churches,” CBC News, July 2, 2021, https://www.cbc.ca/news/politics/trudeau-churches-arson-attacks-1.6088237.

[23] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, The Final Report of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada: Canada’s Residential Schools: The History, Part 1 1939 to 2000 (Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2015), 3, https://ehprnh2mwo3.exactdn.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Volume_1_History_Part_1_English_Web.pdf.

[24] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 3.

[25] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 23–24.

[26] Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 24.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

-

Edward Smith - Dr.

Note that we still don't know if the 215 graves at Kamloops are children as no excavations have yet occurred and we do know that the 751 graves in Saskatchewan are a mix of adults, children, indigenous and European farmers living in the region - this according to the local Indigenous leadership 30.03.2023

-

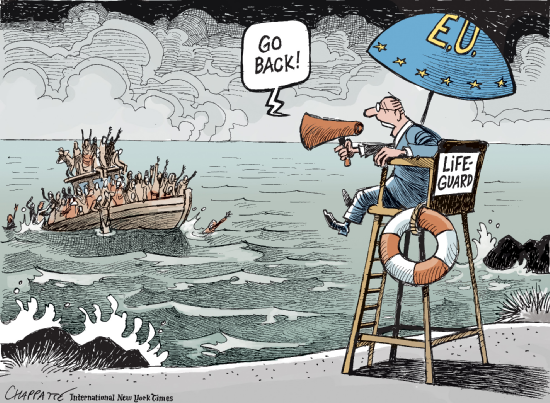

HOW DOES VON DER LEYEN'S DESCRIPTION OF “EUROPEAN WAY OF LIFE” COMPLY WITH EUROPEAN VALUES?

HOW DOES VON DER LEYEN'S DESCRIPTION OF “EUROPEAN WAY OF LIFE” COMPLY WITH EUROPEAN VALUES?

AVİM 30.09.2019 -

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 4

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 4

Ali Murat TAŞKENT 22.10.2015 -

THE NORTH MACEDONIA-BULGARIA DISPUTE AND THE CONFUSING WAY EU DEALS WITH CHALLENGES

THE NORTH MACEDONIA-BULGARIA DISPUTE AND THE CONFUSING WAY EU DEALS WITH CHALLENGES

AVİM 12.01.2021 -

MORE THAN A LOCAL CONFLICT: THE KYRGYZSTAN-TAJIKISTAN BORDER DISPUTE

MORE THAN A LOCAL CONFLICT: THE KYRGYZSTAN-TAJIKISTAN BORDER DISPUTE

Gülperi GÜNGÖR 10.02.2023 -

THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT’S RESOLUTION REGARDING THE 2014 PROGRESS REPORT ON TURKEY

THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT’S RESOLUTION REGARDING THE 2014 PROGRESS REPORT ON TURKEY

Ali Murat TAŞKENT 17.06.2015

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"