On 2-3 March 2023, Armenia's Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan paid a two-day working visit to Germany. Pashinyan's agenda in Germany was quite intense. In Berlin, he met with Chancellor Olaf Scholz and President Frank-Walter Steinmeier. Pashinyan also had a meeting with Konrad Adenauer Foundation's Chairman Norbert Lammert. In the Bundestag, he had two meetings with the Germany-South Caucasus Friendship Group and the Foreign Affairs Committee. Another meeting was with the representatives of the German Eastern Business Association and leading German companies. Besides these meetings, Pashinyan participated in the discussion titled “Security and Stability in the South Caucasus. Armenia's Perspective” at the German Council on Foreign Relations. Before finalizing his visit, he gathered with the representatives of the Armenian organizations in Germany.

The busy schedule of the Armenian Prime minister in Germany is quite notable. When considered in relation to its timing and the context - the ongoing Ukraine-Russia war and the post-2020 Armenia-Azerbaijan and Armenia-Türkiye normalization processes/attempts - Pashinyan's visit to Germany draws further attention for its political implications.

A Deeper and More Comprehensive Engagement

Armenia and Germany have been seeking a deeper and more comprehensive relationship for some time. As stated by Scholz and Pashinyan during their meeting on 2 March, a comprehensive bilateral development cooperation plan that covers diverse spheres such as economy, finance, and science and education was launched out last year. Yet, it is not only the Armenia-Germany bilateral relationship; both leaders underlined the will to enhance the EU-Armenia cooperation based on the Comprehensive and Enhanced Partnership Agreement (signed in 2017; entered into force in 2021).

Notably, at the discussion held at the German Council on Foreign Relations, Pashinyan informed the audience about “a new important format of the Armenia-EU partnership agenda – The Political and Security dialogue, the inaugural meeting of which took place in Yerevan last January” (emphasis added). This is a highly important statement that needs to be taken into account as it reveals that the EU-Armenia engagement is built not only on 'non-political' objectives such as economic development or democratization. Instead, it could be seen that an Armenia-EU relationship built on geopolitical considerations is forecasted. To put it briefly, the new Russia containment policy of the Euro-Atlantic lies at the core of EU's engagement with Armenia. Arguably, as Georgia turns into a disappointment for the Euro-Atlantic capitals, ideas about fortifying – or, if needed, replacing – Georgia with Armenia is becoming a more attractive perspective in the EU, and given the political accord between the two, the US. For now, the result of this Euro-Atlantic outlook in terms of its success is yet to be seen. However, what is certain is Yerevan's enviable talent of building a pro-Western image, while actually being a CSTO member state that has never voted against Russia during the UN votes about the occupation of Crimea or the Russian aggression in Ukraine.

Guarding the 'Democratic Armenia'

In recent years, portraying itself as a democracy is one of the identifiable elements of Armenian foreign policy discourse. In this way, Yerevan intends to strengthen the Western image of Armenia in its search for sympathy and support from the ‘Collective West.’ In Berlin, ‘Armenian democracy’ was one of the repeated emphases of Pashinyan. His speech at the German Council on Foreign Relations was particularly significant in this regard. In this speech, Pashinyan said, “there is no internal threat to democracy in Armenia…But, on the other hand, we have external threats to our democracy. Azerbaijan's continuous escalations, aggressive rhetoric, and hate speech are a great threat to Armenian democracy.” Overall, in Berlin, Pashinyan was diligent to frame the Armenia-Azerbaijan conflict as a conflict between a democracy - Armenia - and an autocracy - Azerbaijan- though he did not use the latter term in his speeches. It could be seen that, by employing the presently popular neo-Cold War rhetoric of democracies vs. autocracies, Pashinyan appeals for Western support against Azerbaijan within the framework of the ongoing Armenia-Azerbaijan normalization negotiations.

Armenia-Azerbaijan Normalization and the Usual Blame Game

Pashinyan tried to convince his interlocutors in Berlin that Armenia was the party seeking normalization, whereas Azerbaijan was the spoiler. Pashinyan alleged that Baku violates the 9 November 2020 Declaration by sustaining unconstructive rhetoric and a belligerent policy. He argued that the occupation of 150 square kilometers of the sovereign territory of Armenia; not repatriating the Armenian prisoners of war (PoWs); and blocking the Lachin corridor - which he deemed a part of the “the large-scale and systematic policy of Azerbaijan aimed at the ethnic cleansing of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh” – are the examples of Azerbaijani hostility towards Armenia.

Not all these claims of Pashinyan, however, hold water. Actually, not one side’s but both sides’ rhetoric is unconstructive and aggressive. In fact, wrist wrestling between Yerevan and Baku goes on without a pause despite the normalization talks mediated by the EU and Russia. The ‘war of words’ is a part of the ‘bargaining process’ between Yerevan and Baku.

Though Pashinyan accuses Baku of blocking the normalization process, it is actually Yerevan that does everything to stall one necessary step to further the process, namely, the border delimitation and demarcation until it gains relative strength to be able to dictate its own terms. This is so because as a result of border delimitation according to valid Soviet-era maps, a number of strategically important spots on the border will remain on the Azerbaijani side. Arguably, this attitude of Yerevan is the main reason why Baku opposes the deployment of EU monitors in the region as it believes this will encourage the former to continue to impede the border delimitation and demarcation as long as possible.

Thirdly, because the border is not delimited, there is no exact borderline. For this reason, determining whether Azerbaijani troops invade the sovereign territory of Armenia or not is technically not possible. In that regard, Baku’s claim that the Azerbaijani troops are stationed within the Azerbaijani sovereign territory is as valid as the Armenian claim of Azerbaijani occupation. Obviously, this complication can be solved only after the border is delimited and demarcated.

Whereas Pashinyan’s claims about Azerbaijani belligerency are discussible, his argument about the PoWs is an outright manipulation. This is so because the Armenian prisoners in Azerbaijan that Pashinyan referred to were not captured during the war. They were detained inside Azerbaijan and charged with being members of armed saboteur groups after the signing of the 9 November 2020 Declaration. Therefore, they are not PoWs as Pashinyan tries to picture them.

Lastly, Pashinyan's picturing of the “blockage” of the Lachin Corridor as Azerbaijani policy of ethnic cleansing of the Armenians in the former Nagorno-Karabakh region is apparently a gross exaggeration. Exaggerating things to extremes is, anyways, an often-observed and well-known habit of Pashinyan. Besides that, however, Pashinyan certainly has a point in arguing for the need for the easing of the tension in this region. For this to happen, illegal activities such as smuggling weapons into Armenian-populated Azerbaijani territories either with or without the consent of Yerevan must come to an end. Unless this happens, calm in the region will just be a good wish, not a reality.

Pashinyan, the Etymologist: Lachin vs. Zangezur

One of the most contested issues between Armenia and Azerbaijan are the questions of Lachin and Zangezur corridors. Hence, it was not surprising that in Berlin Pashinyan also expressed Yerevan's view on these points of contention. Answering a question at the German Council on Foreign Relations, Pashinyan said: “You know, it is very important to note that sometimes the same words can have different meanings in different regions. Thus, usually, when we say corridor in Europe, we mean communication, transportation, etc. But in our case the reality is different.” After this brief 'etymological clarification,' he argued that the 9 November 2020 Declaration mentions only the Lachin Corridor which, he alleged, according to the declaration “should be and is beyond the control of Azerbaijan.” Pashinyan further argued that no other corridor was mentioned in the declaration. Rather, he said, the Declaration stipulated opening of regional communication and transport routes. He added that “there is no point according to which these routes should be outside the control of Armenia. We have repeatedly stated that this is a red line for us.” Pashinyan repeated the same view in Bundestag the next day at the meeting with the members of the Foreign Affairs Committee.

In order to judge whether Pashinyan's arguments hold, one needs to refer to the 6th and 9th articles of the 9 November 2020 Declaration.

The 6th article is as follows:

The Republic of Armenia shall return the Kalbajar District to the Republic of Azerbaijan by November 15, 2020, and the Lachin District by December 1, 2020. The Lachin Corridor (5 km wide), which will provide a connection between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia while not passing through the territory of Shusha, shall remain under the control of the Russian Federation peacemaking forces.

As agreed by the Parties, within the next three years, a plan will be outlined for the construction of a new route via the Lachin Corridor, to provide a connection between Nagorno-Karabakh and Armenia, and the Russian peacemaking forces shall be subsequently relocated to protect the route.

The Republic of Azerbaijan shall guarantee the security of persons, vehicles and cargo moving along the Lachin Corridor in both directions (emphases added).

The 9th article, on the other hand, is as follows:

All economic and transport connections in the region shall be unblocked. The Republic of Armenia shall guarantee the security of transport connections between the western regions of the Republic of Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic in order to arrange unobstructed movement of persons, vehicles and cargo in both directions. The Border Guard Service of the Russian Federal Security Service shall be responsible for overseeing the transport connections.

Subject to agreement between the Parties, the construction of new transport communications to link the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic with the western regions of Azerbaijan will be ensured (emphases added).

As can be seen, Pashinyan is right in arguing the presence and absence of the terms Lachin Corridor and Zangezur Corridor, respectively. However, the same cannot be said when it comes to the rest of his argument.

Articles 6 and 9 oblige both Armenia and Azerbaijan to guarantee the security of transport connections. They also state that Russian security personnel takes responsibility for protecting these routes. Hence, the Declaration implies equity between the two routes.

Besides, there are two points that actually negate Armenia's position. First, Article 6 talks about Russian peacekeepers’ responsibility to control and protect the Lachin Corridor. The consequential point is that Article 4 of the Declaration states “…The peacemaking forces of the Russian Federation will be deployed for five years, a term to be automatically extended for subsequent five-year terms unless either Party notifies about its intention to terminate this clause six months before the expiration of the current term" (emphasis added). Here the idea is clear: Russian peacekeepers are not to be stationed in Azerbaijan's internationally recognized territories forever. Upon the decision of either Armenia or Azerbaijan, Russian peacekeepers will have to leave the sovereign territory of Azerbaijan by the fall of 2025. This brings the question of who will be responsible to control and protect the Lachin Corridor once the Russians leave. This is the critical point that Yerevan tries to withhold because it is obvious that it will be Azerbaijan who will assume these responsibilities since Lachin Corridor is in its sovereign territory. Accordingly, Pashinyan's claim that the Lachin Corridor “should be and is beyond the control of Azerbaijan” does not hold.

Second, though Article 9 does not use the term Zangezur Corridor, it states “unobstructed movement of persons, vehicles and cargo in both directions [between the western regions of Azerbaijan and the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic]” as opposed to Article 6 that stipulates “security of persons, vehicles and cargo moving along the Lachin Corridor in both directions.” Here what Yerevan tries to do is to brush under the carpet is the fact that the expression of “unobstructed movement” much more strongly implies a corridor logic than the expression of “security of movement.” Accordingly, though the 9 November 2020 Declaration includes the term “Lachin Corridor” it actually implies a corridor passing through the Zangezur region of Armenia, and not the Lachin region of Azerbaijan.

Territorial Integrity, but Just Mine

Politics is not always tragic. At times, it is also ironic. This, once again, was observed in Berlin. Since the eruption of the Karabakh conflict in the late 1980s, Azerbaijan argued for the principle of territorial integrity, while Armenia advocated the principle of self-determination. What was seen in Berlin is that now Yerevan has dropped the self-determination argument and adopted the territorial integrity argument against Azerbaijan.

Pashinyan underlined the principle of territorial integrity while alleging Azerbaijan’s occupation of the sovereign Armenian territories and condemning the usage of the term “Western Azerbaijan” (a term that implies that most of the current territory of Armenia historically belongs to Azerbaijan) in Azerbaijani political discourse. Whereas Pashinyan's claims about the occupation of the Armenian territories is disputable, he is right in objecting to the usage of the term “Western Azerbaijan.” However, even in this rightful position, Pashinyan does not sustain a consistent position and eventually contradicts himself.

At the German Council on Foreign Affairs, Pashinyan said “We witnessed the first sprouts of today’s challenges and the collapse of the European security architecture in our region back in 2020 when Azerbaijan unleashed a war against Nagorno-Karabakh.” He also alleged, “In May, 2021 Azerbaijan invaded the territory of Nagorno Karabakh.” It is obvious that a serious leader cannot claim that he recognizes the territorial integrity of another country, while openly arguing that this very same country unleashes a war and invades the territory of a political entity within its own borders. As a leader, Pashinyan has to be aware of this, unless his goal is not provocation or manipulation. Secondly, though he rightly criticizes the usage of the term “Western Azerbaijan,” up until now - even not when normalization talks are carried out between Ankara and Yerevan - Pashinyan has never openly objected to the popular usage of the term “Western Armenia” in Armenia, a term that represents the irredentist delusions of Armenian radicalism that implies Eastern Türkiye actually belongs to Armenia.

Chancellor Scholz: Ignorance, Apathy, or Hypocrisy?

Inconsistencies and manipulations have been in Yerevan's playbook for a long time. Accordingly, the above-mentioned claims and allegations of Pashinyan were not a great surprise for the experts who observe the region from the region. On the contrary, however, some of the statements of Chancellor Scholz were truly astonishing.

During his meeting with Pashinyan, Scholz stated:

…it is more important that Armenia and Azerbaijan go step by step to a long-term solution. The Prime Minister [Pashinyan] presented me with the latest developments in Nagorno-Karabakh, we are concerned about the instability on the border of Armenia and Azerbaijan and the worsening humanitarian situation in Nagorno-Karabakh. The status quo cannot continue and a long-term solution should be achieved for the good of the people.

In this regard, it is necessary to reach a peaceful settlement from the point of view of the territorial integrity of Armenia and Azerbaijan, as well as the self-determination of the citizens of Nagorno-Karabakh. Moreover, all these principles are equal (emphases added).

Scholz is right in saying that the status quo cannot continue. However, he is wrong in other things that he said.

In order to end the status quo and create a new reality of regional peace, stability, and cooperation, parties need to gear up the normalization process, instead of moving step by step slowly. This is so because in the region the risk of escalation still exists and slowing of the normalization process just increases this risk. Furthermore, what is needed is not a “long-term solution” but a final peace.

Secondly, Territorial integrity and self-determination are two main principles of international law. However, it is debatable whether these two have equal weight. The conventional wisdom among international law scholars is that territorial integrity has precedence over self-determination. Besides, self-determination has two variants; external self-determination (secession) and internal self-determination (autonomy, cultural rights, etc. within the mother state). Scholz did not clarify which variant of self-determination he was talking about. This ambiguity, added on top of decades-long Armenian advocacy of external self-determination, while Azerbaijan was open to internal self-determination, raises questions about whether Scholz implied secession of the former Nagorno-Karabakh region. In any case, whereas Pashinyan did not underlined self-determination, but constructively advocated the insurance of the “rights and security of the people of Nagorno-Karabakh,” Scholz's emphasis on self-determination does not appear as a sincere and constructive approach.

Thirdly, it begs an answer to what Scholz really implied by using the expression “the citizens of Nagorno-Karabakh,” instead of, for example, “people of Nagorno-Karabakh,” as Pashinyan did.[1] This cannot be seen as a minor detail since the usage of the word citizen implies the recognition of the existence of a state in the former Nagorno-Karabakh region. Likewise, Scholz's usage of the old name “Nagorno-Karabakh” may be a reason to question Berlin's recognition of Baku's sovereignty on its internationally recognized territories, since Baku has terminated Nagorno-Karabakh as an administrative unit and created Karabakh and Eastern Zangezur economic zones by a presidential decree on 7 July 2021.

* Photograph: primeminister.am

[1] It should be noted that the possibility of a manipulation of Yerevan remains there since the transcript of Scholz’s speech was published on the official website of the Prime Minister of Armenia. It may be possible that that Scholz actually have used a word other than citizen.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

2 APRIL 2017 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN ARMENIA

2 APRIL 2017 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN ARMENIA

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 14.04.2017 -

AN INQUIRY INTO NANCY PELOSI’S VISIT TO ARMENIA

AN INQUIRY INTO NANCY PELOSI’S VISIT TO ARMENIA

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 23.09.2022 -

PASHINYAN'S GERMANY VISIT

PASHINYAN'S GERMANY VISIT

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 09.03.2023 -

THE JUDGEMENT OF THE EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS GRAND CHAMBER ON PERİNÇEK v. SWITZERLAND CASE in PERSPECTIVE - 2: THREE DISQUALIFIED ARGUMENTS AND “THE PREVENTION OF DISORDER”

THE JUDGEMENT OF THE EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS GRAND CHAMBER ON PERİNÇEK v. SWITZERLAND CASE in PERSPECTIVE - 2: THREE DISQUALIFIED ARGUMENTS AND “THE PREVENTION OF DISORDER”

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 23.10.2015 -

THE BACKTRACK OF AUSTRIA AND LUXEMBURG ON THE CHARACTERIZATION OF THE 1915 EVENTS AS GENOCIDE

THE BACKTRACK OF AUSTRIA AND LUXEMBURG ON THE CHARACTERIZATION OF THE 1915 EVENTS AS GENOCIDE

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 21.10.2015

-

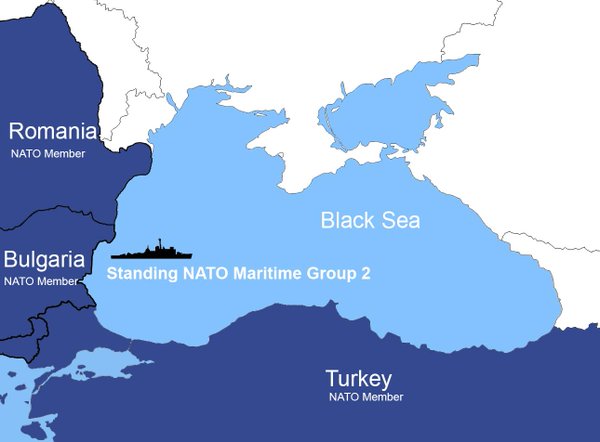

BLACK SEA, A POTENTIAL FRICTION VENUE BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE WEST: TURKEY HOLDS THE KEY TO THE REGION

BLACK SEA, A POTENTIAL FRICTION VENUE BETWEEN RUSSIA AND THE WEST: TURKEY HOLDS THE KEY TO THE REGION

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 13.03.2017 -

THE EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS’ APPROACH TO NEGATIONISM AND REVISIONISM AND SOME DEDUCTIONS ON PERINÇEK V. SWITZERLAND CASE

THE EUROPEAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS’ APPROACH TO NEGATIONISM AND REVISIONISM AND SOME DEDUCTIONS ON PERINÇEK V. SWITZERLAND CASE

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 16.11.2015 -

FROM THE DRAWERS OF ANKARA TO THE DUSTY SHELVES OF ARMENIA: ZURICH PROTOCOLS

FROM THE DRAWERS OF ANKARA TO THE DUSTY SHELVES OF ARMENIA: ZURICH PROTOCOLS

Tutku DİLAVER 16.03.2018 -

BREXIT: NEW PARADIGM SHIFT FOR GLOBALIZATION AND SIGNAL FOR NEW WORLD ORDER

BREXIT: NEW PARADIGM SHIFT FOR GLOBALIZATION AND SIGNAL FOR NEW WORLD ORDER

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 27.01.2017 -

MILITARY USE OF INLAND WATERWAYS IN THE BLACK SEA REGION

MILITARY USE OF INLAND WATERWAYS IN THE BLACK SEA REGION

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 16.04.2021

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"