To read the second article of this series, click here.

On July 17th, a year after its effective date, Russia withdrew from the Black Sea Grain Initiative (Initiative on the Safe Transportation of Grain and Foodstuffs from Ukrainian Ports) To remind, between July 22nd, 2022 and July 17th, 2023 the Grain Initiative was extended three times (November 18th, 2022 for 120 days; March 17th, 2023 for 60 days, and May 18th, 2013 for 60 days). Following the withdrawal, Russia began its missile strike campaign on the Ukrainian grain storage facilities in Odesa (the major Ukrainian port city) and some other southern cities, and those on the Danube River, including the ones in Reni, a transport hub on the Danube bordering Romania. These strikes reportedly destroyed 60,000 tons of grain. Not surprisingly, these developments piled up concerns over global food security. Western capitals accused Russia of “weaponizing food” and blackmailing the world with hunger.

Russia retorted these accusations by asserting that the promises made to secure unimpeded Russian food and fertilizer exports to world markets were not upheld. Russia claims that setting obstacles against its food and fertilizer exports is a violation of the MoU between the UN Secretariat and Russia (Memorandum of Understanding between the Russian Federation and the Secretariat of the United Nations on promoting Russian food products and fertilizers to the world markets) that was signed on the same day with the Grain Initiative, which Russian commentators usually refer to as the “Russian part of the grain deal”. Kremlin Spokesman Dmitry Peskov stated that “Russia would immediately return to the implementation of the Black Sea agreements as soon as the Russian part of the grain deal is fulfilled.” As such, Moscow has not sealed the Grain Initiative once and for all. Rather, it left the door open for negotiations.

Russia has several concrete demands that it grounds on the aforementioned UN-Russia MoU. These are 1) reconnection of the Russian Agricultural Bank to the SWIFT payment system; 2) relaunch of the Togliatti-Odessa ammonia pipeline; 3) lifting of the restrictions on exports of agricultural machinery and spare parts to Russia; 4) permission for the Russian ships to enter foreign ports; 5) unblocking of transport logistics, transportation insurances, and Russians assets abroad. Besides these, Russia blames the West for hypocrisy by pointing out that the lion’s share of the Ukrainian grain goes to developed countries in Europe instead of the poor countries in the Global South, which are the ones that are threatened by mass hunger. The US-led collective West replies to Russia by asserting that there are no sanctions in place on Russian food and fertilizer exports.

The Grain Exports in Figures

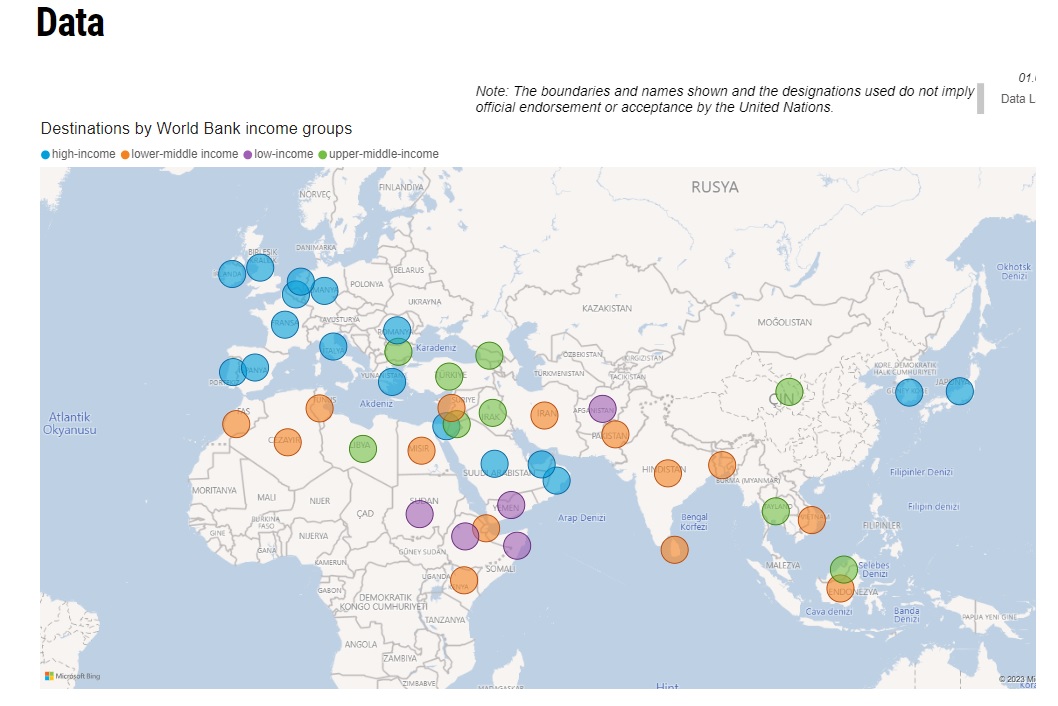

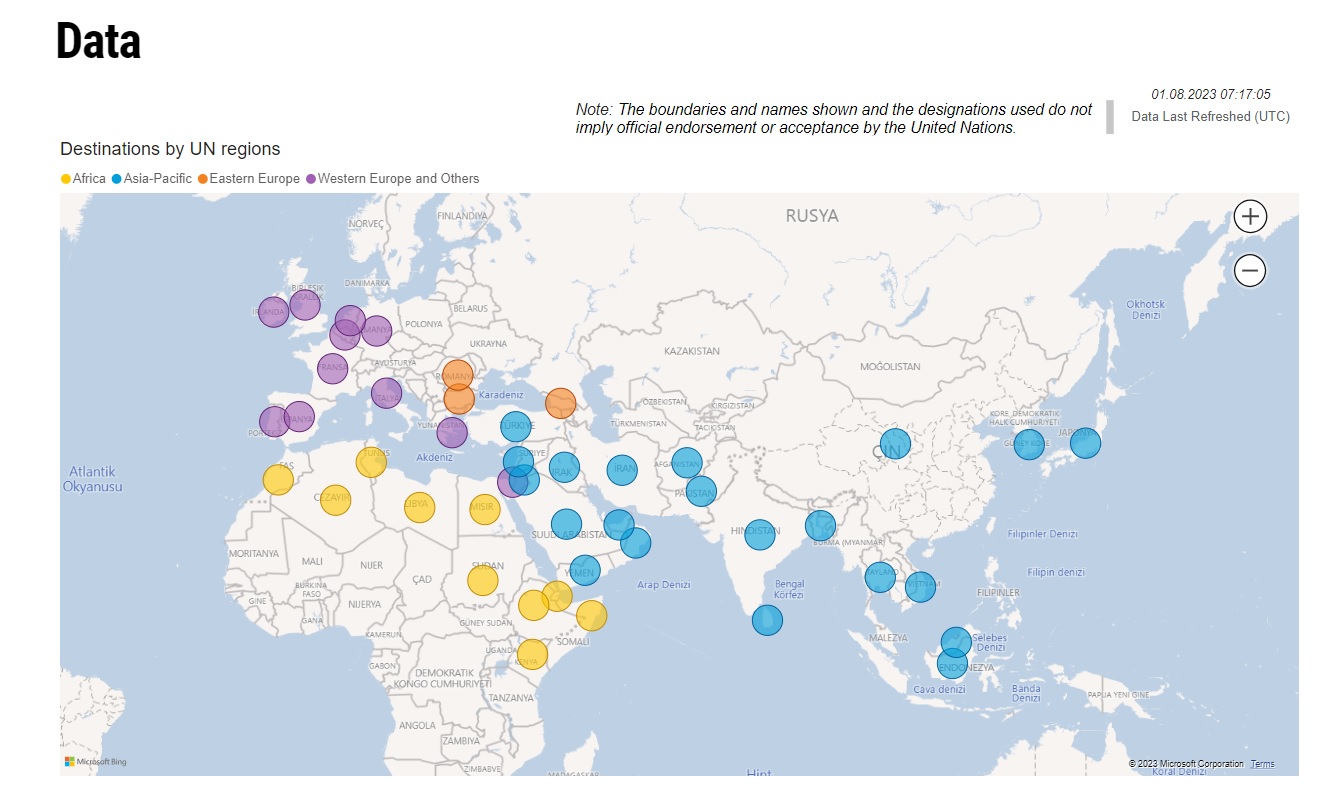

The Black Sea Grain Initiative has enabled the export of 32,9 million cubic tons of Ukrainian grain to 45 countries across Europe, Africa, and Asia since it was signed in late July 2022.

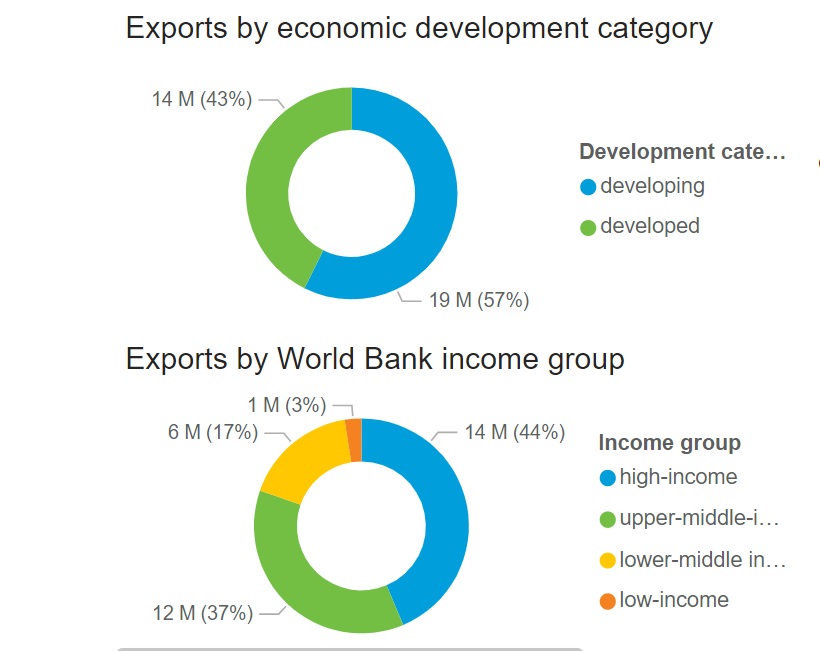

The UN data reveals some interesting facts about Ukrainian grain exports. According to this data, 42.65% of the Ukrainian grain was shipped to developed countries, whereas 57.35% went to developing countries.

As to the World Bank’s income categorization, 17 high-income countries received 43.65%; 9 upper-middle-income countries received 36.7%; 14 lower-middle-income countries received 17.15%; and 5 low-income countries received 2.5% of the exported Ukrainian grain.

Source: United Nations Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre (https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative/data)

Source: United Nations Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre (https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative/data)

With respect to regions, 21 Asia-Pacific countries (geographically ranging from Japan to Türkiye, and including China, the biggest importer of the Ukrainian grain) got 46,25 %; 12 European countries, Israel and Georgia got 41,51%; and 10 African countries got 12,24 % of the Ukrainian grain exported from the Black Sea ports.

.jpg)

Source: United Nations Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre (https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative/data)

Source: United Nations Black Sea Grain Initiative Joint Coordination Centre (https://www.un.org/en/black-sea-grain-initiative/data)

The figures confirm Russia’s claim that although poverty and the risk of hunger in some of the poorest global south countries were brought forward to push for the Grain Initiative and its continuation, it is the rich countries that receive the bulk of the Ukrainian grain. This fact, indeed, refutes much of the humanitarian arguments of the collective West. As to this contradiction, it should be underlined that the MoU between the UN and Russia notes that the “cooperation between the Russian Federation and the Secretariat is to also prevent hunger and aggravating food security issues - primarily in developing and the least developed countries - …” (emphasis added), revealing that elevating the dire situation in poor countries was a relevant motive for the signing of the document.

Not only the US-led collective West but also the UN answer this criticism by arguing that the Grain Initiative is important to counter the risk of hunger in vulnerable poor countries as it enables Ukrainian grain supplies to reach world markets, which results in the reduction of global food prices. According to the data of the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, supply of the Ukrainian grain to world markets resulted in a decrease in global food prices by 11.6% between July 2022 and July 2023 (and 23,4 % compared to the peak of the prices reached in March 2022). This decrease in the prices helped different aid agencies to provide more foodstuff to needy communities in the Global South. Furthermore, the UN states that the Grain Initiative “has allowed the World Food Programme (WFP) to transport more than 725,000 tons of wheat to help people in need in Afghanistan, Ethiopia, Kenya, Somalia, Sudan, and Yemen. Ukraine supplied more than half of WFP’s wheat grain in 2022, as was the case in 2021.” As of July 2023, the portion of the Ukrainian grain increased to 80%.

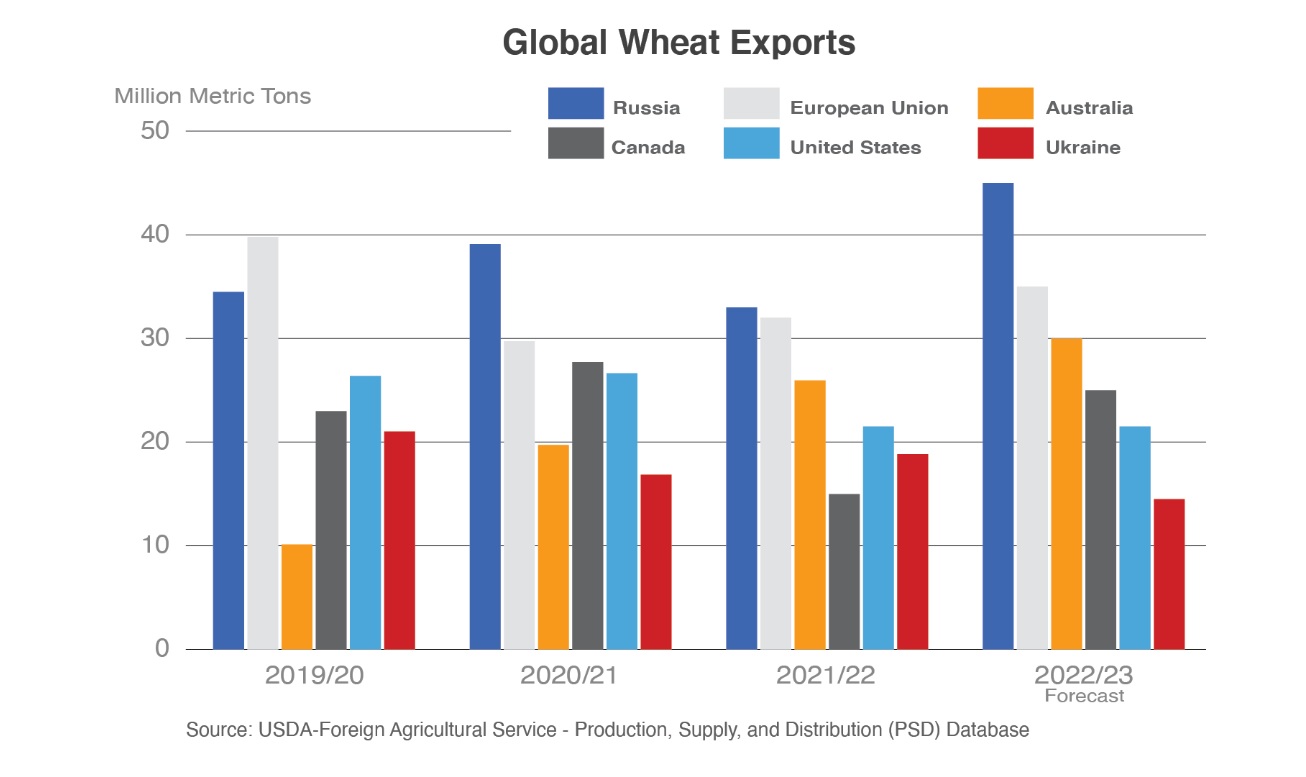

The data provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service (FAS) also induces some question marks about Russia’s complaints about Western impediments to its grain exports. The FAS forecasts that Russia will reach record-high wheat exports in 2022/23. It also states, “Despite the Russian government claims of export challenges, Russia’s grain and oilseed exports have thrived during the current marketing year with ample supplies and competitive prices.” The FAS forecasts a 36% rise in Russian wheat exports in 2022/2023 compared to the previous year.

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service (https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/russia-grain-and-oilseed-exports-expand)

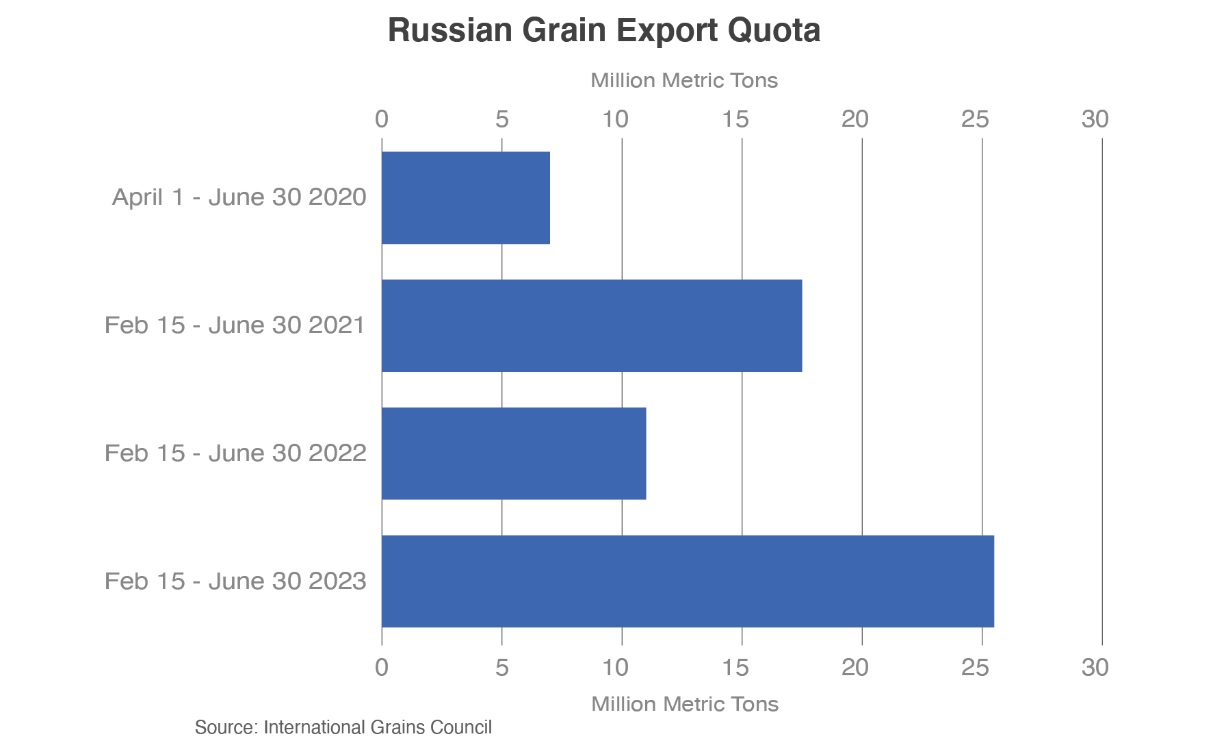

According to the FAS, Russian “export volumes could be even larger, but the Russian government continues to apply export taxes and quotas, trade-restricting measures that are self-imposed.”

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service (https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/russia-grain-and-oilseed-exports-expand)

It should also be noted that the FAS also claims that Russian grain exports by vessels indeed increased in the first 10 months of the marketing year for 2022/23 compared to the previous year.

.jpg)

Source: U.S. Department of Agriculture Foreign Agricultural Service (https://www.fas.usda.gov/data/russia-grain-and-oilseed-exports-expand)

If the data of the FAS is accurate (this disclaimer is, indeed, needed particularly at the time of war when battles are not just fought on the battleground but also in the information space, at which the West is quite skilled), Russia’s claim of Western hindrance of its agricultural exports gets rather dubious. Certainly, land transportation has a significant share in the total Russian grain export. Yet its exports by vessels through the Black Sea have also increased in the 2022/23 marketing year. Here the point is that though the US-led political West seeks to hurt the Russian economy by sanctions, it is not exactly successful in this endeavor. It appears that despite its exclusion from the SWIFT payment system and other hurdles, Russia was able to find ways to overcome Western-imposed economic pressures. The US statistics of Russian grain exports are an admission of the relative failure of the Western sanctions.

The FAS data points out some other realities, as well. Though Russia is blamed for causing food prices to increase by pulling out from the Grain Initiative, its record-high exports have been an important factor in the decrease in prices this year. In addition, whereas a significant portion of the Ukrainian grain is exported to rich countries, Russia’s exports mostly go to middle-income and low-income countries in the Middle East, North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa. According to some reports, 25% of the African imports are supplied by Russia.

To be continued...

*Photograph: UN Black Sea Initiative Joint Coordination Centre

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

THE KARABAKH CONFLICT AND THE LAWFARE OF ARMENIA: ARMENIA’S CAMPAIGN FOR REMEDIAL SECESSION (I)

THE KARABAKH CONFLICT AND THE LAWFARE OF ARMENIA: ARMENIA’S CAMPAIGN FOR REMEDIAL SECESSION (I)

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 27.10.2020 -

THE KARABAKH CONFLICT AND THE LAWFARE OF ARMENIA: ARMENIA’S CAMPAIGN FOR REMEDIAL SECESSION (II)

THE KARABAKH CONFLICT AND THE LAWFARE OF ARMENIA: ARMENIA’S CAMPAIGN FOR REMEDIAL SECESSION (II)

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 11.11.2020 -

THE NAGORNO-KARABAKH ISSUE FROM A JURIDICAL POINT OF VIEW: THE CASE OF CHIRAGOV AND OTHERS V. ARMENIA

THE NAGORNO-KARABAKH ISSUE FROM A JURIDICAL POINT OF VIEW: THE CASE OF CHIRAGOV AND OTHERS V. ARMENIA

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 26.06.2015 -

BECOMING THE PART OF THE PROBLEM: THE FAULTY POLICIES OF THE WEST IN EURASIA AND THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

BECOMING THE PART OF THE PROBLEM: THE FAULTY POLICIES OF THE WEST IN EURASIA AND THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 11.08.2015 -

AN ANALYSIS OF THE POLITICS IN ARMENIA AFTER THE “VELVET REVOLUTION”

AN ANALYSIS OF THE POLITICS IN ARMENIA AFTER THE “VELVET REVOLUTION”

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 01.06.2018

-

REVIVAL OF THE QATAR-TÜRKİYE NATURAL GAS PIPELINE PROJECT

REVIVAL OF THE QATAR-TÜRKİYE NATURAL GAS PIPELINE PROJECT

Bekir Caner ŞAFAK 16.04.2025 -

FAR-RIGHT VIOLENCE AND TERRORISM RISES IN GERMANY: NATIONAL SOCIALIST UNDERGROUND (NSU) TERRORIST GROUP AND THE MURDERS OF EIGHT TURKISH-GERMAN CITIZENS

FAR-RIGHT VIOLENCE AND TERRORISM RISES IN GERMANY: NATIONAL SOCIALIST UNDERGROUND (NSU) TERRORIST GROUP AND THE MURDERS OF EIGHT TURKISH-GERMAN CITIZENS

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 26.08.2019 -

APRIL 24 AND THE IGNORED FIRST WORLD WAR

APRIL 24 AND THE IGNORED FIRST WORLD WAR

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 30.04.2024 -

CHINA IN AFGHANISTAN

CHINA IN AFGHANISTAN

Özge Nur ÖĞÜTCÜ 18.05.2017 -

BECOMING THE PART OF THE PROBLEM: THE FAULTY POLICIES OF THE WEST IN EURASIA AND THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

BECOMING THE PART OF THE PROBLEM: THE FAULTY POLICIES OF THE WEST IN EURASIA AND THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 11.08.2015

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"