The Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (“Extraordinary Chambers” or ECCC in short), which was established to try the officials of the Khmer Rouge regime that had ruled Cambodia between 1975-1979, reached a genocide verdict on 16 November 2018 concerning two high ranking Khmer Rouge regime officials; Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan.[1] This verdict also has importance in terms of the inconsistencies of the genocide allegations concerning the 1915 Events.

The Khmer Rouge regime under the leadership of Pol Pot (Saloth Sar), which ruled Cambodia between 1975-1979, sought to transform the country into a self-reliant, classless, and agricultural utopian society within the framework of an extreme interpretation of Marxism.[2] The Khmer Rouge regime spent a considerable amount of effort in order eliminate or suppress any factors that it thought would impede the achievement of this goal. Within this effort, the regime resorted to various methods such as mass execution, deportation, forced marriage and procreation, prohibition of religious ceremonies and traditions, and forced-labor resulting in exhaustion or death. A wide section of Cambodian society such as former Cambodian regime members and their families, intellectuals, ethnic Vietnamese and Cham Muslims (both of which were viewed as foreign and harmful), and Buddhist monks (who were viewed as “worms” and “leeches”) became victimized due to the Khmer Rouge regime’s methods. Famine and epidemics spread throughout the country and the economy imploded as a result of the regime’s unrealistic policies. It is estimated that at least 1.7 million people lost their lives as a result of the Khmer Rouge regime’s ruthless conduct,[3] and it is indicated that the regime’s surviving victims carry deep psychological wounds. In later years, the Khmer Rouge regime rose to worldwide infamy because of its brutality, and Cambodia came to be known as the “Killing Fields” due to what had occurred in its past. Some authors and researchers had argued that certain actions of the Khmer Rouge regime constituted genocide. However, no competent court had delivered a verdict along such lines until November 2018, so this genocide characterization had remained as an allegation until now.

The Khmer Rouge regime collapsed in 1979 and its leadership dispersed around the country, while Pol Pot died in 1998 under house arrest. In time, some members of the Khmer Rouge regime defected to join the ranks of the new Cambodian government. Even today, victims and perpetrators live side by side in various locations across Cambodia. Furthermore, it is indicated that that the present Prime Minister of Cambodia, Hun Sen, is a former middle-rank member of the Khmer Rouge regime.[4] Despite this social complexity, in time, more and more calls have been made to try the surviving members of the Khmer Rouge regime.

The trials that had been carried out after the collapse of the Khmer Rouge regime were found to be deficient in terms of legal norms. In order to more carefully examine these painful events and to have the perpetrators tried according to international standards, the Cambodian government reached to an agreement with the United Nations. Within this context, an UN-backed independent Cambodian court composed of Cambodian and foreign judges, prosecutors, and lawyers was established and it was tasked with implementing both Cambodian and international law. This court, with the full official name of “Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia for the Prosecution of Crimes Committed during the Period of Democratic Kampuchea”, became fully operational in 2007.[5] In the practice of law, the Extraordinary Chambers is classified as a “hybrid”, “internationalized”, or “mixed” court. Although there are other courts with similar structure, Cambodia’s Extraordinary Chambers is, for now, considered to be unique due to its structure and operating mechanism.[6]

The jurisdiction of the Extraordinary Chambers was determined from the very beginning. The court is tasked with trying only the senior leadership of the Khmer Rouge regime (Democratic Kampuchea) and those who were most responsible for the crimes committed by the regime between April 1975 and January 1979. This means that, for the sake of maintaining social peace in Cambodia, the low and middle-ranking members of the Khmer Rouge regime were exempted from being tried. Since the number one perpetrator, Pol Pot, had died, the court focused on other suspects, and investigations were thus launched against nine individuals.[7] However, since 2007, only three people including Nuon Chea (Deputy Secretary of the Communist Party of Kampuchea) and Khieu Samphan (Head of State of Democratic Kampuchea) have been convicted by the court.

Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan had already been convicted by the Extraordinary Chambers of committing crimes against humanity during a previous legal case. Alongside other accusations, the current case pertained to the accusation that some of the actions of Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan constituted genocide. In this context, the prosecutors attempted to demonstrate that some of the actions of Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan were congruent with the definition of the international legal term “genocide”.[8]

To remind the reader, the 1948 Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide defines the term “genocide” as follows:

“Article II- In the present Convention, genocide means any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

(a) Killing members of the group;

(b) Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

(c) Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

(d) Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

(e) Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”[9]

In the 1948 Genocide Convention, the intent to destroy a national, ethnical, racial, or religious group simply because they are that group (simply because of who they are), meaning the element of “special intent” (dolus specialis), plays a key role. During any case seen in a competent court as described by the 1948 Genocide Convention, the existence of a “special intent” and that actions were specifically taken because of this intent to destroy must be proven without leaving any room for doubt. Hence, in accordance with its tasks, Cambodia’s Extraordinary Chambers analyzed countless documents and old statements of the Khmer Rouge regime, conducted comprehensive investigations, and listened to the testimonies of a multitude of people. As stated earlier, in the context of the latest case involving Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan, the prosecutors attempted to prove that the actions of these two individuals carried the attributes of genocide.[10]

In its press release[11] pertaining to its verdict delivered on 16 November 2018 for the case numbered 002/02 (the most recently seen case involving Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan), the Extraordinary Chambers made the following points:

“Today, the Trial Chamber of the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) convicted former senior Khmer Rouge leaders NUON Chea and KHIEU Samphan of genocide, crimes against humanity and grave breaches of the Geneva Conventions of 1949. The crimes were committed at various locations throughout Cambodia during the Democratic Kampuchea period from 17 April 1975 to 6 January 1979.”

The court convicted both Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan of carrying out genocide against the Vietnamese “ethnic, national, and racial” group and convicted only Nuon Chea of carrying out genocide against the Cham Muslim “ethnic and religious” group.[12] The court determined that these two individuals had been part of a “joint criminal enterprise”, and in this context had engaged in other crimes such as enslavement; imposition of hard labor with water and food deprivation; deportation; imprisonment; torture; persecution on political, religious, and racial grounds; and forced marriage and rape. Due to these crimes, the court sentenced Nuon Chea and Khieu Samphan to life imprisonment.

The court determined that a country-wide policy was implemented between 1975 and 1976 to expel from Cambodia the Vietnamese living in the country, that Vietnamese civilians were subjected to mass killings during certain incidents, and that hundreds Vietnamese civilians and soldiers were subjected to torture and inhumane conditions and killed in the S-21 Security Center.

Additionally, the court determined that the religious and cultural activities of the Cham Muslims were banned country-wide, that they were forced to eat pork and were prevented from worshipping and speaking their own language, that mosques were demolished and Qurans were burned, and that the Cham people were held under arrest and were subjected to mass killings at Wat Au Trakuon and Trea Village Security Center.

Finally, the court announced that it would publish the justification for its verdict at a later date.

From what can be understood from the Cambodian government’s statements,[13] barring any appeals, this case will be the last to be seen by the Extraordinary Chambers (update: Khieu Samphan has filed an appeal against the verdict[14]). The reason for this is that the operational expenses of the Extraordinary Chambers was deemed to be too high by the public (so far, the operational expenses of the court has reportedly been 300 million dollars) and the Cambodian government is worried that proceeding with further trials could lead social conflicts. The Cambodian government has expressed its wish to close this bloody chapter in the country’s history, move on, and look towards Cambodia’s future.

As can be understood from its press release, Cambodia’s Extraordinary Chambers has sought to deliver its genocide verdict against the Khmer Rouge officials based on relevant documents and within the framework of the criteria of the 1948 Genocide Convention. In contrast to this, the genocide allegations put forth regarding the 1915 Events lack such seriousness. As we have indicated in many of our previous articles,[15] the genocide allegations regarding the 1915 Events remove the term “genocide” from its legal framework and arbitrarily use it for various purposes. Within this process, these allegations also resort to fabrications, distortions, and exaggerations.

Let us leave aside for a moment the fact that the 1948 Genocide Convention cannot be applied retroactively (meaning, to the year 1915) due to international legal norms. The chain of events referred to as the 1915 Events do not fit into the definition of “genocide” provided by the 1948 Genocide Convention.[16] There are no authentic documents proving that the Ottoman government of the period had intended to exterminate its Armenian subjects by implementing its relocation policy (all documents claimed to prove a genocidal intent by the Ottoman government have been debunked, although this has not stopped some individuals from nevertheless using such debunked documents).[17] Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that the Ottoman government had sought to protect its Armenian subjects undergoing relocation and that it had punished individuals who had mistreated the Armenians during the relocation.

In short, it is not possible for the genocide allegations regarding the 1915 Events to be taken seriously in light of the 1948 Genocide Convention. It is precisely because of this reason that actors who put forth the genocide allegations have begun to publicize the 1915 Events within the framework of other legal terms (such as crimes against humanity). At the same time; in order to keep alive the genocide allegations known to be based on weak grounds and to create publicity about them; these actors lobby to have parliament resolutions adopted and to have statements made by religious institutions (under the guise of religious solidarity), produce and distribute content through various media channels, recruit media personalities to their cause, and publish so-called academic works with dubious methodologies.

The verdict given by the Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia for the case numbered 002/02 has served to remind everyone that “genocide” is a strictly defined legal term and that the only authority that can pass judgements on this term is a competent court as defined by the 1948 Genocide Convention. Indeed, international news that have covered this development have indicated to their readers that “genocide” is a legal term.[18] It will be beneficial to analyze this development more thoroughly upon the publication of the Extraordinary Chambers' justification of its verdict for case numbered 002/02.

*Photo: United Nations

[1] “Press Release - NUON Chea and KHIEU Samphan Sentenced to Life Imprisonment in Case 002/02,” Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) official website, November 16, 2018, https://www.eccc.gov.kh/en/document/court/summary-judgement-case-00202-against-nuon-chea-and-khieu-samphan

[2] “Khmer Rouge: Cambodia's years of brutality,” BBC, November 16, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-pacific-10684399

[3] “ECCC at a Glance – January 2018,” Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) official website, accessed November 26, 2018, https://www.eccc.gov.kh/sites/default/files/eccc%20at%20a%20glance%20-%20january%202018.pdf

[4] “Khmer Rouge leaders found guilty of Cambodia genocide,” BBC, November 16, 2018, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-46217896

[5] “Introduction to the ECCC,” Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) official website, accessed November 26, 2018, https://www.eccc.gov.kh/en/introduction-eccc ; “ECCC at a Glance – January 2018.”

[6] “Is the ECCC a Cambodian or an international court?” Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) official website, accessed November 26, 2018, https://www.eccc.gov.kh/en/faq/eccc-cambodian-or-international-court ; “Are there any other courts in the world like the ECCC?” Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) official website, accessed November 26, 2018, https://www.eccc.gov.kh/en/faq/are-there-any-other-courts-world-eccc

[7] “All Cases,” Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) official website, accessed November 26, 2018, https://www.eccc.gov.kh/en/all-cases

[8] “Khmer Rouge leaders found guilty of Cambodia genocide.”

[9] “Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide,” United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner, accessed November 29, 2018, https://www.ohchr.org/en/professionalinterest/pages/crimeofgenocide.aspx

[10] “Khmer Rouge leaders found guilty of Cambodia genocide.”

[11] “Press Release - NUON Chea and KHIEU Samphan Sentenced to Life Imprisonment in Case 002/02.”

[12] “Press Release - NUON Chea and KHIEU Samphan Sentenced to Life Imprisonment in Case 002/02.”

[13] “Khmer Rouge leaders found guilty of Cambodia genocide” ; “No more Khmer Rouge prosecutions, says Cambodia,” The Guardian, November 19, 2018, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2018/nov/19/no-more-khmer-rouge-prosecutions-says-cambodia

[14] “Appeal Register - KHIEU Samphan Defence’s Urgent Appeal Against the Trial Chamber Judgment Pronounced on 16 November 2018,” Extraordinary Chambers in the Courts of Cambodia (ECCC) official website, accessed November 30, 2018, https://www.eccc.gov.kh/en/document/court/appeal-register-khieu-samphan-defences-urgent-appeal-against-trial-chamber-judgment

[15] For example, please see: Mehmet Oğuzhan Tulun, “The Dutch Parliament’s February 22 Decision on the 1915 Events,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), Analysis No: 2018/5, February 22, 2018, https://avim.org.tr/en/Analiz/THE-DUTCH-PARLIAMENT-S-FEBRUARY-22-DECISION-ON-THE-1915-EVENTS

[16] Mehmet Oğuzhan Tulun, “Some Criticisms Regarding Prof. Dr. Erik-Jan Zürcher’s Centennial Statement,” Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM), Analysis No: 2015/7, April 21, 2015, https://avim.org.tr/en/Analiz/SOME-CRITICISMS-REGARDING-PROF-DR-ERIK-JAN-ZURCHER-S-CENTENNIAL-STATEMENT

[17] Ömer Engin Lütem ve Yiğit Alpogan, "Review Essay: Killing Orders: Talat Pashaʼs Telegrams and the Armenian Genocide,” Review of Armenian Studies, Issue 37 (2018), https://avim.org.tr/tr/Dergi/Review-Of-Armenian-Studies/37

[18] For example, please see: “Khmer Rouge leaders found guilty of Cambodia genocide.”

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

GENOCIDE AND GERMANY

GENOCIDE AND GERMANY

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 10.01.2017 -

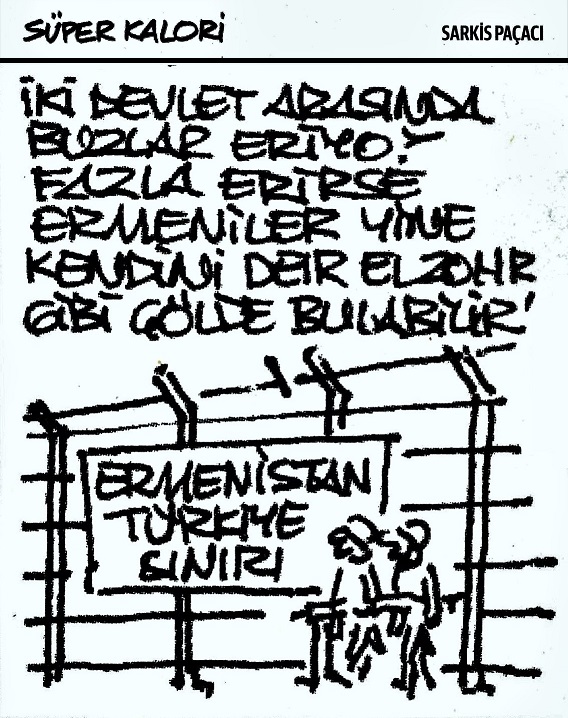

OPPOSITION AGAINST THE TURKEY-ARMENIA NORMALIZATION PROCESS THROUGH THE USE OF CARTOONS

OPPOSITION AGAINST THE TURKEY-ARMENIA NORMALIZATION PROCESS THROUGH THE USE OF CARTOONS

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 13.05.2022 -

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 5

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 5

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 22.10.2015 -

ARMENIA AND THE VENERATION OF TERRORISTS - II

ARMENIA AND THE VENERATION OF TERRORISTS - II

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 16.09.2019 -

GENOCIDE ALLEGATIONS, PROPAGANDA MOVIES, AND A 90-MILLION-DOLLAR FIASCO

GENOCIDE ALLEGATIONS, PROPAGANDA MOVIES, AND A 90-MILLION-DOLLAR FIASCO

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 14.07.2020

-

THE EU’S WORRIES ON THE US’ MILITARY EXISTENCE/ABSENCE

THE EU’S WORRIES ON THE US’ MILITARY EXISTENCE/ABSENCE

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 11.01.2021 -

GERMANY’S FAR-RIGHT TERRORISM AND THE TIMID NSU CASE VERDICT

GERMANY’S FAR-RIGHT TERRORISM AND THE TIMID NSU CASE VERDICT

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 25.09.2020 -

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 4

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 4

Ali Murat TAŞKENT 22.10.2015 -

HYDROPOLITICS, TRANSBOUNDARY RIVERS, AND THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

HYDROPOLITICS, TRANSBOUNDARY RIVERS, AND THE SOUTH CAUCASUS

Tutku DİLAVER 11.04.2022 -

RELATIONS OF US SENATORS WITH FOREIGN LOBBIES: THE CASE OF MENENDEZ

RELATIONS OF US SENATORS WITH FOREIGN LOBBIES: THE CASE OF MENENDEZ

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN - Tuğçe TECİMER 17.09.2024

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"