There exists a doubt in the European Union (EU) that the Union itself has turned out to be the hostage of some of its own member countries. The relevance of this idea has gained ground since there exists several examples to justify this situation. While the relationship between Greece, the Greek Cypriot Administration of Southern Cyprus (GCASC) and EU on the Eastern Mediterranean demonstrates this idea, the Bulgaria-North Macedonia tension on North Macedonia’s accession to EU fortifies it as an argument.

North Macedonia’s accession adventure to EU dates to 2004 when Macedonia got the chance of being one of the first post-Yugoslav states to become a candidate for EU membership[1]. However, for years North Macedonia was prevented from EU accession by Greece due to North Macedonia’s former official name[2]. According to Greece, the former Republic of Macedonia was claiming the cultural heritage of Greece by its name referring to the ancient Macedon Kingdom and its ancient emperor Alexander the Great[3]. To overcome this challenge, the former Republic of Macedonia changed its official name to Republic of North Macedonia in 2018. Yet, this was not the only impediment that lay between North Macedonia and its accession to EU.

On 17 November 2020, Bulgaria made it clear that it would veto the EU accession process of North Macedonia since Skopje has ignored to address certain concerns of Sofia[4]. In the past, Bulgaria had been one of the great supporters of North Macedonia’s accession to EU and the two countries even signed an “Agreement on Good Neighborly Relations” with each other on 2 August 2017[5]. One of the provisions of this agreement was to establish a joint historical commission to find a solution to the common historical and linguistic claims[6]. However, Bulgaria accuses the North Macedonia of violating this agreement by not providing enough investment in infrastructure which would connect the two countries and solve the historiographic differences by building a binational historical commission[7].

On the other hand, the dispute between Bulgaria and the North Macedonia is far more complicated than this, since the core of the dispute is about the denial of the Macedonian identity and language by the Bulgarian government. It is known from the official speeches of Sofia that various Bulgarian officials denied the Macedonian identity and claimed that Macedonians are in fact Bulgarians who are unaware of their Bulgarian identity[8]. In addition to this, the Bulgarian Academy of Sciences refused to refer to “Macedonian” as a different language than Bulgarian and suggested that “Macedonian” is a standardized version of a Bulgarian dialect[9].

According to President Pedarovski of North Macedonia, its language and unique history gives the country its own identity[10], but for Bulgarian officials, the separate North Macedonian identity does not really exist. It is true that the North Macedonian territory had been ruled by Ottoman Empire, Serbia, and Bulgaria respectively. It is also true that there exists some relation between the Macedonian and Bulgarian languages and same is valid for the cultures of the two countries. Yet, Bulgaria demands its narrative of history to be accepted with a new bilateral treaty. As to Sofia, “A Macedonian language or ethnicity did not exist until 2 September 1944. Their creation was part of the overall building of a separate non-Bulgarian identity by Yugoslavia, aimed at cutting the ties between the population of the region and Bulgaria[11]”. Bulgarian officials also included in their declarations that the EU accession talks must include special monitoring for Skopje’s compliance with these rules in school textbooks and national holidays[12]. Another striking -or extreme- demand of Sofia is about the limitation of the Macedonian language. According to Bulgaria, after the accession of North Macedonia to EU takes place, it should be declared that the mention of the “Macedonian language” only exists in the constitution of the Republic of North Macedonia[13]. Bulgarian officials also said that “The enlargement process must not legitimize the ethnic and linguistic engineering that has taken place under former authoritarian regimes[14]”. As a normal response, officials from Skopje stated that they will not accept such a discussion on this topic in an interview to EU Observer. Apparently, the aggressive behavior of Bulgaria does not comply with the agreement on Friendship, Cooperation and Good Neighborliness.

After the Bulgarian veto on the accession process of North Macedonia to EU, the Bulgarian government was also accused of violating the right of self-determination and forcefully imposing an identity on the Macedonian nation[15]. Thus, this behavior of Bulgaria allegedly means that Bulgaria does not respect the sovereignty of the North Macedonia. Despite this, Sofia responded to Skopje by revealing that the North Macedonia should not count on Bulgarian support or assistance if the country continues to embrace “totalitarian historical narratives”[16]. Those behaviors and responses have caused a cooling down on the relations of the two countries which had been smoothened after the 2017 agreement.

Other than those facts, it is certain that the Bulgarian veto on North Macedonia’s accession to EU has provided several uncertainties and put the region’s stability at risk[17]. Moreover, as a result of this, the trade and investment of both sides will decrease as well. Since Bulgaria is its biggest trade partner, North Macedonia will be at a disadvantage in this situation[18]. However, it will be a loss for Bulgaria as well, since North Macedonia is one of the few countries Bulgaria has trade surplus with.

In addition to those, this dispute also has political consequences that are more serious than the economic outcomes. Euroscepticism may rise in North Macedonia since the country has received the second veto in its accession process[19]. Thus, this veto may lead to more destabilization in the Balkans.

At the same time, it is a fact that the Bulgarian move is a challenging test for the EU[20]. Analysts have made it clear that Bulgaria and Romania were accepted to EU without providing the necessary requirements and conditions for the EU membership[21] and it is known that Germany was behind this policy. Now, even Germany has made it clear that it was disappointed by the Bulgarian behavior, meaning that Germany sides with North Macedonia in this conflict[22].

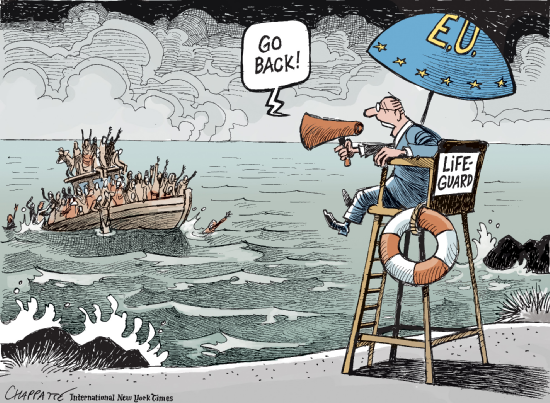

It is clear that the EU has not been functioning as it should be lately. The question, the answer to which is self-evident, is whether forcing one country and nation to change its official name for accession process complies with the core values of EU. How this disrespect to that country’s sovereignty can be remedied is another question. Another crucial point that must be considered is that the EU’s unsuccessful attempt to reach consensus on its enlargement policy forms weakness and harms the overall credibility of the EU[23]. Apparently, tougher diplomatic actions are needed to solve this veto dispute and the possible damage it may cause. Yet, the North Macedonia-Bulgaria dispute is only one of the challenges of EU since credibility of EU has taken a major hit by the current blocking of Belarus sanctions by GCASC due to the current Eastern Mediterranean dispute with Turkey. The Eastern Mediterranean issue between Turkey, Greece and GCASC remains as an unsolved challenge for EU and between different sides. Just as in the Bulgaria-North Macedonia dispute, the EU once again failed to find a common policy that has an equal approach between the different sides. In this sense, many challenges lay ahead for the EU other than the economic ones that were created by the coronavirus pandemic. In general, the view of EU as being a hostage of some of its member countries has started to become the dominant one for many countries. However, as this policy can be traced back to the accession granted to GCASC, attributing this problem to a small circle of countries may be a misleading notion.

*Photograph: RFE/RL

[1] Katerina Kolozova, “On The Macedonian-Bulgarian Dispute and Historical Revisonism”, Al Jazeera, December 7, 2020, https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2020/12/7/on-the-macedonian-bulgarian-issue

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] İdlir Lika, “Bulgarian Veto and EU’s Growing Credibility Problem”, Anadolu Agency, December 11, 2020, https://www.aa.com.tr/en/analysis/opinion-bulgarian-veto-and-eu-s-growing-credibility-problem/2073623

[5] Kolozova, “On The Macedonian-Bulgarian Dispute and Historical Revisonism”.

[6] “2020 Bulgaria: Bulgaria exports its problems to North Macedonia”, Ifimes.org, October 1, 2020, https://www.ifimes.org/en/9908

[7] Kolozova, “On The Macedonian-Bulgarian Dispute and Historical Revisonism”.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] Andrew Rettman, “Does Macedonia Really Exist?”, EU Observer, December 14,2020, https://euobserver.com/enlargement/150370

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Branimir Jovanovic, “The EU Should Act Resolutely After the Bulgarian Veto”, WIIW, December 15,2020, https://wiiw.ac.at/the-eu-should-act-resolutely-after-the-bulgarian-veto-n-476.html

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Ibid.

[19] Ibid.

[20] “2020 Bulgaria: Bulgaria exports its problems to North Macedonia”.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Jovanovic, “The EU Should Act Resolutely After the Bulgarian Veto”.

[23] Lika, “Bulgarian Veto and EU’s Growing Credibility Problem”.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

“QUIET DIPLOMACY” IN NAGORNO KARABAKH CONFLICT AND ARMENIAN ELECTIONS

“QUIET DIPLOMACY” IN NAGORNO KARABAKH CONFLICT AND ARMENIAN ELECTIONS

AVİM 24.04.2018 -

HOW DOES VON DER LEYEN'S DESCRIPTION OF “EUROPEAN WAY OF LIFE” COMPLY WITH EUROPEAN VALUES?

HOW DOES VON DER LEYEN'S DESCRIPTION OF “EUROPEAN WAY OF LIFE” COMPLY WITH EUROPEAN VALUES?

AVİM 30.09.2019 -

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 6

CHAPTER BY CHAPTER SYNOPSIS AND REVIEW OF TURKS AND ARMENIANS: NATIONALISM AND CONFLICT IN THE OTTOMAN EMPIRE BY JUSTIN MCCARTHY - 6

AVİM 22.10.2015 -

DASHNAK FEDAIS: HEROES OR CALAMITIES OF THE ARMENIAN PEOPLE?

DASHNAK FEDAIS: HEROES OR CALAMITIES OF THE ARMENIAN PEOPLE?

AVİM 20.12.2019 -

ARMENIA’S DESPERATE SEARCH FOR FOREIGN INTERVENTION AND ITS HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS: “THREADS OF CONTINUITY”

ARMENIA’S DESPERATE SEARCH FOR FOREIGN INTERVENTION AND ITS HISTORICAL ANTECEDENTS: “THREADS OF CONTINUITY”

AVİM 14.10.2020

-

THE BATTLE TO CONTROL THE NARRATIVE OVER KARABAKH: ARMENIAN CIVILIAN SAFETY VS. AZERBAIJANI STATE SOVEREIGNTY

THE BATTLE TO CONTROL THE NARRATIVE OVER KARABAKH: ARMENIAN CIVILIAN SAFETY VS. AZERBAIJANI STATE SOVEREIGNTY

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 06.10.2023 -

2019 ARMENIAN PATRIARCH OF ISTANBUL ELECTION

2019 ARMENIAN PATRIARCH OF ISTANBUL ELECTION

Mehmet Oğuzhan TULUN 25.12.2019 -

EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN ENERGY: AN OPPORTUNITY OR A DANGER?

EASTERN MEDITERRANEAN ENERGY: AN OPPORTUNITY OR A DANGER?

Tutku DİLAVER 01.10.2018 -

2 APRIL 2017 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN ARMENIA

2 APRIL 2017 PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS IN ARMENIA

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 14.04.2017 -

TURKEY HAS ASSUMED THE CHAIRMANSHIP-IN-OFFICE OF THE SOUTH EAST EUROPE COOPERATION PROCESS (SEECP)

TURKEY HAS ASSUMED THE CHAIRMANSHIP-IN-OFFICE OF THE SOUTH EAST EUROPE COOPERATION PROCESS (SEECP)

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 17.07.2020

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"