The German colonial empire committed multiple atrocities in Africa in the past century. Germany now faces the prospect of a historical reckoning. So far, Germany, among other issues, has engaged three negotiation processes in Africa involving reparations. In that respect, a negotiation process started in 2015 between Germany and Namibia regarding the systemic massacres of the Herero and Nama people of Namibia, which even some German government officials have referred to as being genocidal. Another African country which put forward similar assertions against Germany is Tanzania. The Tanzanian government claims that tens of thousands of people were tortured and killed by German soldiers to eliminate rebels during the period between 1905 and 1907. In line with these claims, Tanzania started a court process in 2017. Last in line is Burundi. In 2020, the Burundi gvernment established a panel of experts to determine the extent of damages caused by colonizers, namely Germany and Belgium, and the associated cost.

AVİM has touched upon the issue of colonial violence by Germany in Africa in previous articles.[1] This article will examine the case of Tanzania. In the upcoming articles, the case of Namibia will be re-examined in the light of recent developments.[2] The case of Burundi will also for the first time be examined from the perspective of violence committed by German and Belgian colonial powers.[3]

Tanzania As A Resource Site

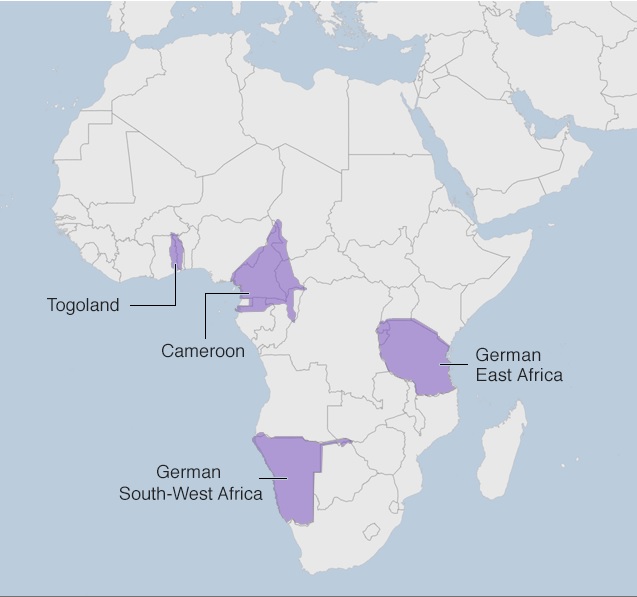

During the period of 1885-1919, Germany was among the leading European colonial powers in Africa, ranking third at the time behind the United Kingdom and France. The German Empire extended from South West Africa (now Namibia) to the German East Africa at the time. German East Africa included the territory of today's Burundi, Rwanda, and Tanzania excluding Zanzibar. On the western side of Africa, the Empire stretched towards Togo, Ghana, and Cameroon. The rule of the German Empire in Africa was very brief, continuing for a little more than three decades. After losing in World War I, Germany had to relinquish its overseas territories.[4]

Among German East African colonies, Tanzania (conquered in 1880), suffered violent repression coming from the German Empire.

Tanzania was important for the German Empire for its various resources. Among these were agricultural products, crops such as sisal, cotton, and plantation-grown rubber. The Empire also received sustainable earnings from items such as coffee, copra, sesame, and peanuts.[5] However, among the most important resources was gold. It can be stated that the first mining activity took place in Tanzania during German colonial period. Beginning with the discovery of gold in the Lake Victoria region in 1894, the German Empire benefited substantially from all these resources.[6]

Tanzania As An Experimentation Site

Tanzania, then known as Tanganyika, was a difficult region to rule for the German Empire. Since its first conquest, the German Empire in general and specifically the local German administrators implemented various experimental practices in Tanzania. Indeed, factors such as taxation, forced labor, and replacing indigenous leaders with foreign agents were put forth as the cause of the famous Maji Maji uprising.

One of the experiments the local German administrators focused on was the method of taxation. Once taxation had entered into force, it proved as another resource that the Germans could use to demonstrate their strength towards the local population. Salt and gun tax was initially imposed, triggering a great deal of displeasure among the local population. Later, in 1905, the "house and hut tax" was substituted with a "head tax" towards all local men. This exacerbated the displeasure of the local population. Even though the local population was being introduced to the concept of “ready cash” by the Ordinance of 1899, the local population was still not ready to pay the German Empire with cash.

In order ensure the strong continuation of the taxation policy, in 1906, the local Governor von Götzen informed the Empire that “The suggestion that taxing the blacks should be given up is tantamount to abandoning the colony.”[7] Under Von Götzen’s orders, harassment of local population, especially the Chiefs, continued.

During this period, the German Empire was of the belief that it could play the local elite population against each other. During the early period of colonization, the Empire had created a complicated legal system. Local tribal chiefs were referred to this legal/court system for each trouble they had. The system was designed not to solve problems but to ensure that the local population could not unite.[8]

Another experimentation was the Akida system. This was the practice of replacing the indigenous leaders with foreign agents. In fact, the term Akida predated the arrival of German Empire to the region. Prior to the arrival of German Empire, the Akida served the coastal towns in a special function. The individual was a prominent member of the younger generation and was a prominent war leader in the region. His responsibilities were to keep order and control public festivities. The Akida answered to Liwali (an Arab or African governor of a town, usually a district headquarters) in the region. He was appointed or recognized by the Sayyid of Zanzibar. The concept was adopted by the German Empire, but it altered the roles of the Akida. Few of the Akida’s were indigenous to their region. Most were literate men from different regions. Their purpose was the representation of the German Empire’s bureaucratic tradition of administration.[9]

This and other factors turned the entire German East Africa, but especially the current Tanzania region, into a powder keg. The move that exploded keg was the initiation of a large-scale African cotton-growing program that brought all the factors together in large scale. In 1902 a new governor decided to initiate large-scale African cotton-growing.

The cotton growing program in the northern coast had failed. Despite the recommendations of his advisers, the governor believed in the high number of production results. Thus, he ordered the creation of cotton agricultural areas in each neighborhood. According to this experiment, each area would be under the control of the local headman.[10] Despite the fact that the Governor had promised to pay 35 cents to cotton workers, this was considered as “forced labor” by the local population. Forced labor was not a new practice for the German Empire. The Empire had used forced labor for projects such as infrastructure works. However, the scale and severity of this project had increased the level of disgruntlement among the local population. The cotton project caused the local men to be separated from their homes and families for a long period of time. This caused the women to assume both traditional male and female responsibilities in their society. This type of change in the social fabric was the last straw concerning the experiments conducted by the German Governors targeting the local population. The protests that subsequently turned into the Maji Maji rebellion. The Akidas were among the first casualties of the German Bureaucratic apparatus during this turmoil. [11]

Violence as a Method of Control

“Hongo or the European, which is the stronger? Hongo!” was the password of the Maji Maji rebellion (“Hongo” was a spirit medium named Kinjikitile Ngwale, who practiced folk Islam that incorporated animist beliefs and claimed to be possessed by a snake spirit). The rebellion spread throughout the provinces. The Maji Maji rebellion started from the base of the society and spread to other segments. It lasted two years. Initially, the overstretched German colonial army did not acknowledge it as a threat. Different segments of the society gathered against Germans for different reasons. Initially, this tactic worked. However, at the end, the German army under the command of Governor von Götzen quelled the rebellion, with devastating results; almost 300,000 people died. The large number of deaths cannot only be attributed to the resistance of the Tanzanian people against the German Empire. In that respect, one must also pay close attention to the methods employed by the German Empire. Governor von Götzen did not believe that victory could only be achieved militarily. He believed that the Tanzanian society also had to be subdued. Based on the advice of military advisers, von Götzen decided to utilize starvation tactic against the entire local population. German Captain Wangenheim wrote to von Götzen; "Only hunger and want can bring about a final submission. Military actions alone will remain more or less a drop in the ocean."[12] This eventually broke the spirit of the Tanzanian rebellion and subdued the local population. However, it also left scars that are still felt today.

The Long Road

Tanzania has demanded reparations for Germany’s action during the colonial era, yet Germany has still not provided a satisfactory response. Tanzania started the procedures for the initial phase of reparations in 2017. However, the German government has managed to delay negotiations by making certain small moves. Among these are the return of objects which the German Empire stole during its colonization of Tanzania. Another such move is by being the second largest environmental aid donor of the Tanzanian state. The last small move by Germany is being the third biggest customer for Tanzania’s tourism industry. Yet, these moves to cover up historical violence have worked only for a limited amount of time since Tanzania is now demanding reparations for Germany’s actions during the colonial era. The Tanzanian state seems to be as assertive as the Herero and Nama people of Namibia to compel Germany to acknowledge the acts of the German Empire as being genocidal.[13]

Facing History: The Humboldt Forum

Recent developments indicate that Germany has started to face its past acts. Among these developments is, as indicated above, the return of stolen artifacts to their original homes. For example, Hendrik Witbooi was an important Nama leader of Namibia in the late 19th and early 20th century who had revolted against German Empire’s power. Despite his opposition to German rule, he had nevertheless embraced Christianity during his youth because of the influence of the missionaries in the then "South West Africa." Witboois’ belongings are part of this German return program. His belongings were stolen in 1893 during an attack carried out by German colonial troops. Later in 1902, they were donated to the Linden Museum in Stuttgart. A bible and a whip belonging to this well-known Namibian leader have recently been returned to Namibia.[14]

Another such artifact is the Tanzanian tribal Chief Mkwawa's skull. It was returned to Tanzania as part of the Treaty of Versailles. However, Tanzania is still awaiting all the other artifacts stolen throughout the period of colonization to be returned to their homeland. It is believed that, among these artifacts, Germany currently holds 8000 African bones. Among these are the remains of Mangi Meli. Mangi Meli, a Tanzanian war hero, was the leader of the Chaga tribe who had revolted against the German Empire. He was hanged and disembodied, and his remains were taken to Germany during the colonial period. The fact that Meli's remains have not been returned to his tribe has had a mental toll on his people. The Chaga tribe believes that since Mangi Meli’s remains have not been buried properly, there has not been proper rainfall since his hanging. The impact of this kind of colonial pillaging has had an impact on the traditions of local people. At different times, such manner of inconsiderate acts have destroyed local people’s ritual, leaving lasting social traumas.[15]

The Humboldt Forum is an exhibit for the unethically taken objects from Africa. It is the newest edition to the Museums in Europe. Germany’s Minister of Culture Monika Grütters, and the German Association of Museums published a code of conduct in December 2018 that outlined how it could be determined if an object was acquired “unethically” or “unlawfully” by today’s standards. Yet, there are two issues with this “code of conduct”. First, the document is not binding, and second, the decision maker is the curator.[16]

In fact, the Humboldt Forum itself is a monument for the colonialist era. As can be remembered, the Berlin Conference was the reason for the start of Germany’s colonization of Africa. Before the Berlin Conference, the number of African artifacts in Germany were 3,361. At the end of colonization period, the number of African artifacts in Germany grew to over 50,000.[17] It should be noted that these unethically acquired artifacts left behind a trail of psychical and cultural destruction all over the continent after the Scramble of Africa. European colonizers of the past, a century and a half after the Scramble of Africa, must return African belongings to their true owners.

*Photo: https://www.bbc.com

[1] Mehmet Oğuzhan Tulun, “Genocide And Germany,” Center For Eurasian Studies (AVİM) 2017, no. 3 (January 10, 2017), https://avim.org.tr/en/Analiz/GENOCIDE-AND-GERMANY; Mehmet Oğuzhan Tulun, “Genocide And Germany - II,” Center For Eurasian Studies (AVİM) 2017, no. 31 (October 18, 2017), https://avim.org.tr/en/Analiz/GENOCIDE-AND-GERMANY-II.

[2] Jason Burke and Philip Oltermann, “Namibia Rejects German Compensation Offer over Colonial Violence,” The Guardian, August 12, 2020, https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/aug/12/namibia-rejects-german-compensation-offer-over-colonial-violence.

[3] “Burundi to Demand €36 Billion from Germany, Belgium for Colonial Rule: Report,” Deutsche Welle, August 16, 2020, sec. News, https://www.dw.com/en/burundi-to-demand-36-billion-from-germany-belgium-for-colonial-rule-report/a-54589695.

[4] William Roger Louis, Ends of British Imperialism: The Scramble for Empire, Suez, and Decolonization (New York: I.B. Tauris, 2006), 240–50.

[5] John Iliffe, Tanganyika under German Rule 1905-1912 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1969), 64,100,167.

[6] Tanzania Mining Laws and Regulations Handbook Volume 1 Strategic Information and Laws, vol. Strategic Information And Regulations (Washington, DC: Intrnational Business Publication, 2016), 36.

[7] Peter Mgawe, Monique Borgerhoff Mulder, and Sarah-Jane Seel, The History and Traditions of the Pimbwe (Dar es Salaam: Mkuki na Nyota Publishers Ltd, 2014), 35.

[8] Mgawe, Mulder, and Seel, 34–36.

[9] Iliffe, Tanganyika under German Rule 1905-1912, 180–93.

[10] John Iliffe, “The Organization of the Maji Maji Rebellion,” The Journal of African History 8, no. 3 (1967): 497.

[11] Mgawe, Mulder, and Seel, The History and Traditions of the Pimbwe, 35–37.

[12] Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa (London: Abacus Little, Brown Book Group, 1991), 856; “Kinjeketile and the Maji Maji Rebellion,” Deutsche Welle, April 23, 2018, sec. World, https://www.dw.com/en/kinjeketile-and-the-maji-maji-rebellion/a-43349054.

[13] Oliver Moody, “Germany under Pressure to Pay for Colonial Sins,” The Times, February 6, 2020, https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/tanzania-puts-germany-under-pressure-to-pay-for-colonial-sins-z09f7sxxs; Burke and Oltermann, “Namibia Rejects German Compensation Offer over Colonial Violence”; Jane Ayeko-Kümmeth, “Tanzania to Press Germany for Damages for Colonial Era ‘Atrocities,’” Deutsche Welle, February 9, 2017, sec. Africa, https://www.dw.com/en/tanzania-to-press-germany-for-damages-for-colonial-era-atrocities/a-37479775.

[14] Ayeko-Kümmeth, “Tanzania to Press Germany for Damages for Colonial Era ‘Atrocities’”; Moody, “Germany under Pressure to Pay for Colonial Sins.”

[15] Tarisai Ngangura, “The Colonized World Wants Its Artifacts Back,” Vice, December 7, 2020, sec. World News, https://www.vice.com/en/article/5dpd9x/the-colonized-world-wants-its-artifacts-back-from-museums-v27n4.

[16] Christine Coester, “German Museums Pushed to Review Colonial-Era Artifacts ‘Blind Spot,’” Handellsblatt, September 5, 2018, https://www.handelsblatt.com/english/politics/african-treasures-german-museums-pushed-to-review-colonial-era-artifacts-blind-spot/23582200.html?ticket=ST-9667229-W5xwKnn1UaBvUMcNb4d9-ap4.

[17] Jacob Kushner, “In Germany, a New Museum Stirs up a Colonial Controversy,” National Geographic, December 16, 2020, sec. History & Culture, https://www.nationalgeographic.com/history/2020/12/germany-humboldt-forum-stirs-colonial-controversy/.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

FRANCE AND GREECE HAVE FINALLY AGREED: EU ACCESSION TALKS BEGIN WITH ALBANIA AND NORTH MACEDONIA

FRANCE AND GREECE HAVE FINALLY AGREED: EU ACCESSION TALKS BEGIN WITH ALBANIA AND NORTH MACEDONIA

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 08.04.2020 -

ASEAN’S DEFICIENCY IN DEALING WITH SECURITY ARENA

ASEAN’S DEFICIENCY IN DEALING WITH SECURITY ARENA

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 12.11.2018 -

EU’S CENTRAL ASIA STRATEGY 2019: BELATED AND SELF CENTERED

EU’S CENTRAL ASIA STRATEGY 2019: BELATED AND SELF CENTERED

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 11.07.2019 -

ABUSING SRI LANKA TERRORIST ATTACKS TRAGEDY AS A PRETEXT FOR PROPAGATING FALSE GENOCIDE CLAIMS

ABUSING SRI LANKA TERRORIST ATTACKS TRAGEDY AS A PRETEXT FOR PROPAGATING FALSE GENOCIDE CLAIMS

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 29.04.2019 -

FROM SYMBOLISM TO SCRUTINY: THE TRANSFORMATION OF FRANCE'S GENOCIDE CLAIMS

FROM SYMBOLISM TO SCRUTINY: THE TRANSFORMATION OF FRANCE'S GENOCIDE CLAIMS

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 01.07.2025

-

THE UN GENERAL ASSEMBLY REJECTED AND CONDEMNED HOLOCAUST DENIAL AND RECALLED THE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BASIS OF ITS REJECTION

THE UN GENERAL ASSEMBLY REJECTED AND CONDEMNED HOLOCAUST DENIAL AND RECALLED THE INTERNATIONAL LEGAL BASIS OF ITS REJECTION

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 04.02.2022 -

EU’S CENTRAL ASIA STRATEGY 2019: BELATED AND SELF CENTERED

EU’S CENTRAL ASIA STRATEGY 2019: BELATED AND SELF CENTERED

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 11.07.2019 -

THE VISA OBSTACLE FOR TURKISH CITIZENS AND THE EU'S JUSTIFICATIONS

THE VISA OBSTACLE FOR TURKISH CITIZENS AND THE EU'S JUSTIFICATIONS

Hazel ÇAĞAN ELBİR 10.10.2024 -

D.L. PHILLIPS’S DIPLOMATIC HISTORY OF THE TURKEY-ARMENIA PROTOCOLS 3

Ömer Engin LÜTEM 29.03.2012 -

ANZAC DAY: “THERE IS NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE JOHNNIES AND THE MEHMETS TO US WHERE THEY LIE SIDE BY SIDE” AT GALLIPOLI. IS THIS THE CASE FOR OTHER COUNTRIES?

ANZAC DAY: “THERE IS NO DIFFERENCE BETWEEN THE JOHNNIES AND THE MEHMETS TO US WHERE THEY LIE SIDE BY SIDE” AT GALLIPOLI. IS THIS THE CASE FOR OTHER COUNTRIES?

Teoman Ertuğrul TULUN 30.04.2019

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"