To read the first article of this series, click here.

To read the second article of this series, click here.

Armenia has been in a chaotic state for the last six months. First, between 27 September and 9 November, it went through a war with Azerbaijan, which eventually ended with the Azerbaijan’s liberation of its occupied territories except for approximately two thirds of Nagorno Karabakh. Then, Armenia’s defeat in the battlefield triggered domestic turbulence. An anti-Pashinyan coalition was quickly formalized under the name Homeland Salvation Movement. In late February, the General Staff demanded Pashinyan’s resignation. This raised a number of critical questions with respect to civilian-military relations and the future of democracy in Armenia.

In this complicated and multi-actor scene, in addition to Pashinyan, opposition, and the General Staff, there is also a fourth actor. This fourth actor is President Armen Sarkissian.

President A. Sarkissian hit international headlines when he refused to sign Pashinyan’s 25 February decree on the dismissal of the Chief of General Staff Onik Gasparyan two times on 27 February and 2 March. Yet, he has been keenly, though cautiously, making political interventions since the signing of the ceasefire deal on 10 November.

Starting from that day, A. Sarkissian began consultations with political factions, civil society actors, and top-ranking clergy. At the same time, he had had meetings with several ambassadors in Yerevan including the French and the US ambassadors, and the EU Delegation. He has also paid visits to Jordan and Russia.

Given that A. Sarkissian is the symbolic Head of State, his consultations and meetings with political factions and opinion leaders in a turbulent time could be taken in stride. His encounters with foreign ambassadors and foreign trips can also be deemed acceptable. Yet, there have been acts by A. Sarkissian that arguably exceed what is expected from a president, who has only symbolic powers and ceremonial duties in a parliamentarian political system.

In his adress on 16 November, just few days after the signing of the ceasefire, A. Sarkissian called on Pashinyan’s resignation or “termination of office in accordance with the Constitution, and early parliamentary elections.” He added that “meanwhile, governing will be handed over to the highly qualified Government of National Accord.” He later repeated on several occasions his three-staged proposal on the resignation of Pashinyan (or the termination of office), formation of an interim government.

A. Sarkissian bases his call on Pashinyan’s resignation by pointing out the situation that Armenia has found itself in after the 2020 Karabakh War. In his addresses and statements, A. Sarkissian argues that the crisis in Armenia is not just about the defeat in the battlefield. Rather, he maintains that Armenia suffers defeats in information warfare, public diplomacy, and state-to-state diplomacy, in addition to the military defeat. He argues that Armenia is in a deep political, economic, social, and psychological crisis. In fact, A. Sarkissian makes a profoundly negative assessment of the thirty or so years of mismanagement of the country. However, he puts the stress on Pashinyan’s term in office.

Within such a framework, he underlines the need to accept the reality (the defeat) as it is, and to make sober assessment of the current situation. Upon that, he stresses the imperative of systematic, institutional, and planned solutions as opposed to focusing on individuals and individualistic remedies. In brief, A. Sarkissian advocates an afresh state building process. In one of his press releases, he explained this perspective as “no matter what we call that new page: ‘New Page’, ‘Restart’, ‘A New Beginning’, ‘The Fourth Republic’ or otherwise, the reality is that we are entering a new stage of history.”

One important element of A. Sarkissian’s arguments is his proposal of a technocratic interim government to give a start to this afresh state building. As one of the examples of this proposal, during a meeting with the youth organizations on 29 December 2020, A. Sarkissian stated that:

I am in favour of the majority speaking, that is why I suggested that the Government should resign, after which a new government should form: a government of national accord. Everyone in that government must be a professional; no one should represent any party or party ideology. It must be short-term and have a clear program. It must enable all political forces to prepare for the elections to be held in a year, and enable the tricolour Armenia to give birth to new parties, new groups, and new individuals [emphasis added].

Likewise, in the above mentioned press release issued on 11 January with the title “Towards the ‘Fourth Republic’ - On the Inevitability of Building a Substantive State,” he expressed this idea as “the [interim] government should be composed of professionals and experts who specialize in specific areas.”

Besides a technocratic interim government, another proposition of A. Sarkissian is a “strong leader,” who would raise up Armenia from its current state. In a press release of the Office of the President, this idea is expressed as follows:

In this context, the President noted the need for a strong leader. “A strong leader is the one who is not afraid of people stronger than him. Strong leaders must be people who not only show the way, and are good managers, but also take responsibility, and at any moment are ready to answer for every mistake made,” said President Sarkissian,

A. Sarkissian’s proposals about the technocratic interim government and the strong leader deserves attention. To begin with the former, A. Sarkissian proposes the technocratic interim government to govern the country only until the early elections, which is supposed to be held in a year. However, the time limitation of the interim government brings about a number of questions.

It may be reasonable to forecast that a technocratic government could help to clear some immediate problems of the country by reforming the electoral code and the law on political parties or even the constitution to provide “the necessary conditions for the early elections in reasonable terms,” as A. Sarkissian suggests. However, A. Sarkissian talks about something much more substantial, namely, afresh state building. This raises the question as to how an interim government with a limited time in the office could accomplish such a big task or how the elected government could carry on the state (re)building given that the anti-Pashinyan coalition is composed of the old elite and there are no significant fresh names in the Armenian political scene.

It may be inferred that A. Sarkissian’s emphasis on the need for a strong man is related to this vacuum. In any case, the idea of a strong man brings about the crucial question of who might be this leader. Some statements of A. Sarkissian incline one to think that his candidate for this position is none other than himself. For example, in the meeting on 29 December 2020, in a spectacle of humbleness, he stated that:

Neither am I a saviour, nor anyone else. But I am ready to guide you, to cooperate with you, advise, and support you for you to take the future of this country in your hands, not just to sit and wait for someone to lead this country instead of you. I am ready to support you in everything. You are the future of this country, not me.”

As to this, it is conspicuous that A. Sarkissian does not refrain from complaining about having not enough executive powers. For example, in a TV interview on 25 November during his visit to Jordan, he stated the following:

My problem is somewhere else. I think I am using only 5-10% of my potential for my country, be it due to constitutional restrictions, or because my partners are not open to cooperation… These are the main reasons. I think I can do more in foreign relations, foreign economy, investments, culture and diplomacy, but I do very little. It is quite difficult for me as I want to work, and I certainly do, but I think I can do much more [emphasis added].

On the same track, on 28 December, he complained that he uses only 3% of his potential (2-7% decrease in a month!) due to limited powers of the president with the following words:

The hardest thing for me in these two and a half years has been the fact that I worked every day, but I gave this country three percent of my potential, I am not an Executive President. My only tool is my word, and the word gives people hope. My dream is to create conditions for the next generation to come to power with their mindset, attitude, culture, devotion, and honesty, and these people to lead the country ten, twenty years forward [emphasis added].

These statements may drive one to think that A. Sarkissian might be planning to run for the Prime Minister. However, on several occasions, he has expressed that he does not intent to become the Prime Minister.

Actually, what we are facing is a quite blurred picture, which makes it difficult to understand what A. Sarkissan’s plan is. A. Sarkissian talks through insinuations rather than clear statements, which makes it difficult to understand what he really means or what his true intentions are. His allusiveness makes it difficult to reach conclusions with respect to his proposals about an afresh state building, technocratic interim government, and the strong leader.

In any case, some points should be noted. First, A. Sarkissian was recommended as the candidate for the President by the former President Serzh Sargsyan in 2018 and was elected to this post by the votes of the deputies in the National Assembly only shortly before the so-called Velvet Revolution. In other words, A. Sarkissian was elected as the President not through a popular vote. Rather, his ascendance to Presidency was de facto an appointment. Second, after serving as the Prime Minister in 1996-1997, for twenty years between 1998 and 2018, A. Sarkissian spent most of his time abroad serving as the Armenian Ambassador to the UK (and Vatican) (1998- 2000 and 2013-2018) and working as senior official at various organizations and institutions. As such, A. Sarkissian is more a senior bureaucrat and a businessperson than a politician with organic ties with Armenian society and a support base. Therefore, it is unlikely that he could mobilize the society to acquire more political power.

For this reason, what he can do to gain political power is conjoining with the existing political forces. As to this, it should be underscored that his three-staged proposal on the resignation of Pashinyan (or the termination of office), formation of an interim government, and early elections ipso facto puts him in an alliance with the opposition that makes the same demands, irrespective whether this is really what A. Sarkissian intends to or not.

To conclude, there are some signs that lead one to think that A. Sarkissian might be testing the possibilities of acquiring executive powers as the President of Armenia with an interim government, technocratic or not, the mandate of which might be longer than expected. Whatever the case may be, what is apparent for now is that A. Sarkissian pursues a more central role in the Armenian politics by portraying himself as the non-partisan ‘wise man.’ Yet, it seems that in the lion’s den of Armenian politics, hard times are ahead for him.

* Photo: President.am

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

THE ‘ARMENIAN QUESTION’ IN UKRAINE - IV: THE PRUDENCE OF OFFICIAL KYIV

THE ‘ARMENIAN QUESTION’ IN UKRAINE - IV: THE PRUDENCE OF OFFICIAL KYIV

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 17.05.2021 -

IS IRAN GETTING MORE ISOLATED?

IS IRAN GETTING MORE ISOLATED?

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 06.01.2023 -

THE ‘ARMENIAN QUESTION’ IN UKRAINE - II: THE ADVOCATES OF THE ‘ARMENIAN CAUSE’ IN UKRAINE

THE ‘ARMENIAN QUESTION’ IN UKRAINE - II: THE ADVOCATES OF THE ‘ARMENIAN CAUSE’ IN UKRAINE

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 10.05.2021 -

DISPLAYING THE ‘NEW KAZAKHSTAN’ IN THE GLOBAL POLITICAL SYSTEM: THE ASTANA INTERNATIONAL FORUM

DISPLAYING THE ‘NEW KAZAKHSTAN’ IN THE GLOBAL POLITICAL SYSTEM: THE ASTANA INTERNATIONAL FORUM

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 13.06.2023 -

A RUSSIAN SOLDIER’S MULTIPLE KILLINGS IN ARMENIA

A RUSSIAN SOLDIER’S MULTIPLE KILLINGS IN ARMENIA

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 19.01.2015

-

ARMENIA IS MARKETING ITS GEO-STRATEGIC POSITION

Alev KILIÇ 08.11.2012 -

RUPEN SEVAG CHILINGIRIAN

RUPEN SEVAG CHILINGIRIAN

AVİM 09.03.2020 -

ARMENIA HAS OPTED TO JOIN THE EURASIAN ECONOMIC UNION

Alev KILIÇ 06.09.2013 -

WHAT KIND OF “RECONCILIATION” IS THE HRANT-DINK FOUNDATION PROMOTING?

WHAT KIND OF “RECONCILIATION” IS THE HRANT-DINK FOUNDATION PROMOTING?

Maxime GAUIN 19.03.2015 -

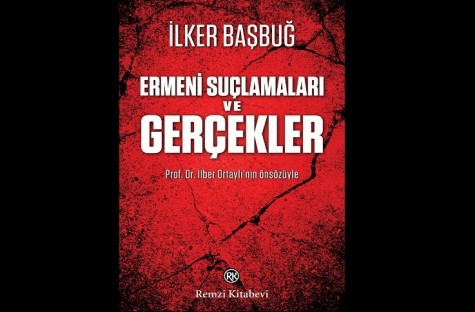

BOOK REVIEW: ARMENIAN ALLEGATIONS AND FACTS (ERMENİ SUÇLAMALARI VE GERÇEKLER)

BOOK REVIEW: ARMENIAN ALLEGATIONS AND FACTS (ERMENİ SUÇLAMALARI VE GERÇEKLER)

Ali Murat TAŞKENT 09.07.2015

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"