Salih Işık BORA*

Intern at AVIM

In September 2013, Vladimir Putin visited Baku accompanied by the Russian Caspian Sea fleet[1]. Within the same month, the Armenian President announced in Moscow that his country would join the Customs Union instead of signing an Association Agreement with the European Union. This event is among many others that demonstrated that Russia is exerting an undeniable influence over Armenia through leverage in the domain of security. The Russian military presence in Armenia, materialised with the air base in Gumru and the creation of a joint army command in December 2016, is extensive. Russia has military commitments to protect Armenia’s borders, notably with Turkey and Azerbaijan. Armenia’s political elite’s dependence on Russia may not even be limited to external threats. Within the framework of the CSTO, there is a Rapid Reaction Force mandate in case of internal instability; so Russia may provide armed support for Armenian authorities should they be unable to suppress an opposition uprising[2].

However, this partnership is not solely based on Armenia’s interests and geopolitical choices. In fact, the alignment with Russia and its Customs Union is not wielding benefits for Armenia. Many economists argue quite the opposite[3]. As the withdrawal from the negotiations about the Association Agreement with the EU shows, Russia does not hesitate to use leverage against Armenia. These are not limited to the revocation of security commitments but also include the blocking of the remittances from the Armenian workers in Russia[4], the increase of gas prices and even supporting regime change. Armenia is deeply integrated to Russia on so many levels as Russian companies control most sectors in the country whether it is energy or telecommunications. Technocrats from these prominent Russian companies often rise to positions of power, notably illustrated with the choice of the new Prime Minister Karen Karapetyan who was a Gazprom executive for many years preceding his term[5]. In fact, the Armenian economy’s dependency on Russia is such that the western sanctions have a destructive effect on Armenia without intending to. Figures close to the Russian decision making circles openly admit the importance of these leverages on the Russian-Armenian relations. Notably, in Alexander Dugin’s words: “Any anti-Russian sentiments in the post-Soviet area will sooner or later result in an outcome similar to Georgia’s and Ukraine’s. [...] there is an alternative for Armenia: Customs Union membership or bloodshed and disappearance from the map.”[6] Moreover, the military intervention in Georgia in 2008 sent a clear signal that Russia will not back down from military confrontation if necessary.

Despite this influence Russia exerts over Armenia, the former Soviet Republic shows interest in establishing other diplomatic ties, notably with the West. During the resurgence of the Karabakh conflict on April 2016, Russia refrained from supporting Armenia’s interests to the extent that it did in the previous conflicts. Arms sales to Azerbaijan have also been increasing. As a result, Russia is not seen as a fully reliable security guarantor. Along with this perception, other reasons also exist: the economic prospects of proximity with the West are incomparably better and the public opinion is leaning towards a more pro-Western attitude notably because of the perceived lack of Russian support in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. The Armenian President’s decision to meet NATO secretary general Jens Stoltenberg in February 2017, the country’s participation in a NATO exercise in Georgia in July 2017[7] and the announcement of a new and less ambitious Trade Agreement with the EU[8] demonstrate Armenia’s willingness to improve its ties with the West even if a real geopolitical shift towards it is extremely unlikely to happen. Nevertheless, Armenia will continue to attempt balancing Russia’s overwhelming influence.

Another actor that Armenia is seeking proximity with is Iran. In fact, the Islamic Republic supported Armenia since the beginning of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict because of various reasons. The Azeri minority in Northwest Iran is perceived as a threat since the independence of Azerbaijan. More importantly, Azerbaijan is Israel’s closest ally in the region[9] and Iranian officials repeatedly claimed that the country could open its air bases for Israeli jets seeking to strike Iran’s nuclear facilities[10]. In return, Azerbaijan accused Iran of supporting radical Islamist organizations and aiming to destabilize the secular republic. Iran is currently seeking proximity with Armenia, although very gradually not to upset its Russian ally which perceives Iran’s increased presence in the South Caucasus as a threat. Apart from the perceived threat from Azerbaijan, Iran aims to transport some of its natural resources to Europe through Armenia; recently a 3.7 billion dollar railway deal is on the table despite Russia’s objections[11].

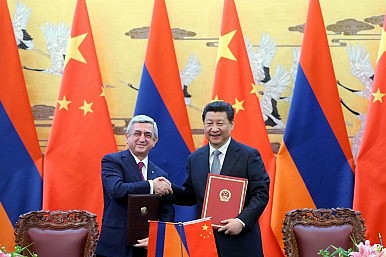

In conclusion, the current situation is one in which Armenia seeks to diversify its diplomatic ties and decrease its dependence on Russia. However, the country does not have the possibility to do so to a significant extent. The army along with the political elites are aligned with Russia and they are unlikely to perpetuate their power otherwise. Nevertheless, NATO is trying to cooperate with Armenia as much as possible and under very favourable and lenient terms. The influential role of the lobby of the Armenian diaspora in the United States Congress as well as the reluctance to recognise the Russian dominance over the Caucasus are the main short term factors. In general, in the foreseeable future, Armenia will cooperate limitedly with NATO while remaining within the Russian sphere of influence. However, the circumstances could change in the medium to long term. Some analysts argue that an increase of European trade through the Southern Caucasus could embolden pro-western Georgia and neutral Azerbaijan while pushing Armenia away from Russia to a certain extent. The end of sanctions on Iran and its integration to the global economy could intensify trade that goes through the Caucasus and draw an increased European and Iranian presence in the region. If the Nuclear deal stands and cooperation deepens between them in the medium to long term[12], the European Union and Iran could even work together to balance Russia in the South Caucasus. Currently, Russia is aiming to block infrastructure projects in the region that doesn’t involve itself. The Transanatolian railway and pipeline, nearing completion, that involved Azerbaijan was a source of tensions between the two countries[13]. Russia also has an interest in the continuing of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict as the instability will impede the connectivity of the South Caucasus to the rest of the world while also providing leverage to Moscow against Yerevan and Baku. Another key variable for the South Caucasus will be the One Belt One Road initiative that aims to connect China with Europe through improved infrastructure. If important portions of trade between East Asia and Europe start flowing through the Caucasus, an increasing number of actors would be involved in the region and Russia’s objective to claim it as part of its sphere of influence would become more difficult. Notably, China has been increasing its investments in the region and this trend is likely to continue. In the meantime, Armenia doesn’t have much of a choice except remaining within the Russian sphere of influence, despite its overtures towards the West in the recent years.

* Salih Işık Bora continues his studies at the University College of Sciences Po Paris and London School of Economics.

[1] Cornell Svante; The European Union: Eastern Partnership Vs Eurasian Union; The Eurasian Union And Its Discontents; 2014.

[2] Grigoryan Armen; Armenia: Joining Under The Gun; Putin’s Grand Strategy; The Eurasian Union And Its Discontents; 2014.

[3] « The Head Of The Car Importers’ Union, Tigran Hovhannissian, As Well As Some Economists Have Warned That Higher Import Duties Applied By The Customs Union Will Result In A Sharp Price Increase And Will Destroy Small Businesses, Leaving The Market To Monopolies, While Retail Prices Of Non-Russian Cars Will Go Up By At Least 50 Percent, And Consumers Will Be Forced To Buy Mostly Russian Cars. » Grigoryan Armen; Armenia: Joining Under The Gun; Putin’s Grand Strategy; The Eurasian Union And Its Discontents; 2014.

[4] Over The Last 5 Years, Remittances Constituted On Average 16% Of Armenia’s Gdp An 89% Of Them Came From Russia According To An Imf Report From 2012(Https://Www.Imf.Org/External/Country/Arm/Rr/2012/062012.Pdf)

[5] Sir Aslan Yavuz; Recent Changes In Armenian Government; Avim Commentary No. 2016/53; 19th October 2016.

[6] Grigoryan Armen; Armenia: Joining Under The Gun; Putin’s Grand Strategy; The Eurasian Union And Its Discontents; 2014.

[7] Abrahamyan Eduard; The Implication Of Nato’s Noble Partner 2017 Exercises In The South Caucasus; The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst; July 11 2017.

[8] Notably, The New Agreement Lacks A Free Trade Component Unlike The One In 2013.

[9] In An 2009 Cable Sent To The Us State Department By The Us Embassy Of Baku, Ilham Aliyev Was Quoted As Saying That The Relation Between Israel And Azerbaijan Is An Iceberg “Nine-Tenths Of It Below The Surface”. Moniquet Claude And Racimora William; The Armenia-Iran Relationship: Strategic Implications For The South Caucasus Region; European Strategic Intelligence And Security Center; January 17th 2013.

[10] Moniquet Claude And Racimora William; The Armenia-Iran Relationship: Strategic Implications For The South Caucasus Region; European Strategic Intelligence And Security Center; January 17th 2013.

[11] Barmin Yuri; Russia’s Relationship With Iran Just Got More Complicated; Russia Direct; January 21st 2016.

[12] The Signing Of A 5 Billion Investment Deal Between The French Energy Company Total And Iran Is A Promising Sign. Especially For The Development Of A Euro-Iranian Energy Corridor Through The Caucasus.

[13] Ismail Alman Mir; Why The Sharp Downturn In Russian-Azerbaijani Relations; The Central Asia-Caucasus Analyst; July 14th 2017.

© 2009-2025 Center for Eurasian Studies (AVİM) All Rights Reserved

No comments yet.

-

TURKEY AND KOREA DRAWING CLOSER

TURKEY AND KOREA DRAWING CLOSER

S. Işık BORA 27.11.2017 -

WHAT FUTURE FOR ARMENIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS?

WHAT FUTURE FOR ARMENIAN-RUSSIAN RELATIONS?

S. Işık BORA 14.08.2017 -

CHINA’S GROWING PRESENCE IN THE CAUCASUS

CHINA’S GROWING PRESENCE IN THE CAUCASUS

S. Işık BORA 01.11.2017

-

“MONTENEGRO AND THE BALKANS” MEETING ORGANIZED BY AVIM AND ANKARA UNI. CENTER OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL RESEARCH

“MONTENEGRO AND THE BALKANS” MEETING ORGANIZED BY AVIM AND ANKARA UNI. CENTER OF INTERNATIONAL ECONOMIC AND POLITICAL RESEARCH

Hande Apakan 17.03.2015 -

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS IN SOUTH CAUCASIA – ALEV KILIÇ

Alev KILIÇ 22.01.2014 -

THE ‘ARMENIAN QUESTION’ IN UKRAINE - I: A POTENTIAL PROBLEM IN A PROMISING RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TURKEY AND UKRAINE

THE ‘ARMENIAN QUESTION’ IN UKRAINE - I: A POTENTIAL PROBLEM IN A PROMISING RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN TURKEY AND UKRAINE

Turgut Kerem TUNCEL 07.05.2021 -

ARAM BEZIKIAN ORPHANAGE AND THE MISREPRESENTATION OF HISTORY

ARAM BEZIKIAN ORPHANAGE AND THE MISREPRESENTATION OF HISTORY

AVİM 17.09.2021 -

TURKEY’S PRESIDENCY OF THE G-20 IN 2015

TURKEY’S PRESIDENCY OF THE G-20 IN 2015

Hande Apakan 04.03.2015

-

25.01.2016

THE ARMENIAN QUESTION - BASIC KNOWLEDGE AND DOCUMENTATION -

12.06.2024

THE TRUTH WILL OUT -

27.03.2023

RADİKAL ERMENİ UNSURLARCA GERÇEKLEŞTİRİLEN MEZALİMLER VE VANDALİZM -

17.03.2023

PATRIOTISM PERVERTED -

23.02.2023

MEN ARE LIKE THAT -

03.02.2023

BAKÜ-TİFLİS-CEYHAN BORU HATTININ YAŞANAN TARİHİ -

16.12.2022

INTERNATIONAL SCHOLARS ON THE EVENTS OF 1915 -

07.12.2022

FAKE PHOTOS AND THE ARMENIAN PROPAGANDA -

07.12.2022

ERMENİ PROPAGANDASI VE SAHTE RESİMLER -

01.01.2022

A Letter From Japan - Strategically Mum: The Silence of the Armenians -

01.01.2022

Japonya'dan Bir Mektup - Stratejik Suskunluk: Ermenilerin Sessizliği -

03.06.2020

Anastas Mikoyan: Confessions of an Armenian Bolshevik -

08.04.2020

Sovyet Sonrası Ukrayna’da Devlet, Toplum ve Siyaset - Değişen Dinamikler, Dönüşen Kimlikler -

12.06.2018

Ermeni Sorunuyla İlgili İngiliz Belgeleri (1912-1923) - British Documents on Armenian Question (1912-1923) -

02.12.2016

Turkish-Russian Academics: A Historical Study on the Caucasus -

01.07.2016

Gürcistan'daki Müslüman Topluluklar: Azınlık Hakları, Kimlik, Siyaset -

10.03.2016

Armenian Diaspora: Diaspora, State and the Imagination of the Republic of Armenia -

24.01.2016

ERMENİ SORUNU - TEMEL BİLGİ VE BELGELER (2. BASKI)

-

AVİM Conference Hall 24.01.2023

CONFERENCE TITLED “HUNGARY’S PERSPECTIVES ON THE TURKIC WORLD"